Marc Myers knows a thing or two about music. After founding the award-winning JazzWax blog and getting noticed by some big-time music editors, the journalist and author found his way over to the Wall Street Journal. As Myers recounts in the acknowledgments section of his latest book, Anatomy of a Song: The Oral History of 45 Iconic Hits That Changed Rock, R&B and Pop, his editor contacted him back in 2011 about writing a column. The subject-matter? Individual songs and their backstories. (“[Songs are] like people and we could profile them,” said the editor.)

But Myers soon realized that many songs weren’t just a one-interview affair; these were living, breathing pieces of poetry that shared the blood of multiple musicians, all with different perspectives on how the finished product came to pass. From there, the idea morphed into more of an “oral history” of each tune, and out of the sum of the column’s parts, came the book (he’s still regularly publishing the column).

“To do this kind of a book, to do these columns, you can’t just do what’s been done,” explains Myers of his work. He tells RealClearLife that he puts in between six and seven hours of research for each song prior to his interviews, because in his mind, he “… [needs] to know more than the artist does about their own song.” His endgame is teaching his readers something completely new about each song.

For the purposes of the book, Myers has distilled it down to 45 hit songs that he believes changed rock history in some way. But by no means is it an “obvious” list; we can almost guarantee that you’ve never heard of Lloyd Price’s “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” and even if you’re familiar with The Rolling Stones’ “Moonlight Mile,” it’s by no means a “Brown Sugar” or “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.”

That said, you’ll still find a number of classic rock radio staples in the book’s page, such as The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me,” Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” and Joni Mitchell’s “Carey”—but you’ll see them in a completely different way than you’ve ever been able to before. Myers clearly has a gift for getting his famous subjects to go deeper into their craft than they ever have before.

While RealClearLife could’ve talked all day with Myers about rock music and his book, we wanted to distill our own group of favorites from his list of 45, and get the author’s reactions about each. What were some takeaways from his interviews with his famous subjects?

Below, you’ll find a clip of each song, along with an explanation from Myers.

The Rolling Stones’ “Street Fighting Man”

Myers interviewed the band’s co-songwriter and guitarist, Keith Richards, about the song. The author got excited when he dropped this little kernel on RealClearLife: “That song is entirely acoustic except for the electric bass [which Richards played on the track].” So that intro? An acoustic guitar played through a primitive tape recorder that Richards used to record on. Even the drum track is a weird one; skins’ man Charlie Watts was playing on a portable drum kit that was sold in the ’30s or ’40s. Below, he talks about the Stones’ oddball lyric-writing process:

“If you look at ‘Street Fighting Man,’ Keith [Richards] writes the music and then writes the lyrics with Mick [Jagger]. Their process was to write out all these lyrics [on paper], and then instinctively, cut [it] into strips and move [the lines] all around. So if you take a look at the Keith Richards chapter [of the book], you get a glimpse into this whacky but highly effective and creative [songwriting process]. They understood, instinctively, that any kind of lyric-writing on paper is going to wind up formulaic. That logic is going to take hold, and you’re going to say, ‘What follows that? And what should follow this? Should this rhyme?’ Really, what [they were] doing with that process, is shattering [it]. It’s almost like they build a car and take a hammer to the windshield.”

The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me”

Myers interviewed the band’s primary songwriter, Ray Davies, and his brother, lead guitarist Dave Davies, about the song (he also talked to Shel Talmy, who produced the song). When the subject of who “invented” the distorted guitars on the track came up, both Davies brothers claimed the feat as his own. “It’s funny what happens over time; people think they did one thing or another, but the truth of the matter is these guys were brothers, and both had anger management issues as many of these artists do,” explains Myers. Here’s the setup of the recording of the famous track:

“What blew my mind is [The Kinks] recorded this song after two failed [singles] at Pye Records. This was their last shot, and they did their best to make it sound ‘garage’ … really crappy. [After their first attempt], they leave [the studio], and then Pye’s production team, which is used to slick pop stuff, cleans it up. So when [The Kinks] came back the next day to hear the playback, Ray [Davies] hit the roof. Ray said: There is no way you’re releasing this. This is not happening. He reaches into his own pocket [to pay for] more studio time, and what they do is slash [it] up. Ray [had] played so many clubs in [London’s] Soho [district], where the sound systems had been basically blown out by high volume. He loved that [coarse] sound. He didn’t want it cleaned up.”

The Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”

Myers interviewed lead singer and the song’s co-writer, Grace Slick, who told him that she imagined herself a “good-looking schoolteacher” when belting it out. Here’s Myers on the song’s origins:

“I said to [Slick], ‘What [the song] has always sounded like to me is a Bolero.’ This steamy, driving, moody … it’s almost like a tango. Then she started telling me about [listening to] Miles Davis’ [album Sketches of Spain] and the influence of … dropping acid and listening to [it] all day long. [The music] became ingrained in her. What’s interesting about this song is her anger at parents for being hypocritical. That parents are drinking and then telling kids not to do drugs. She was motivated to sort of finger-wag parents with her song, and get them really upset. But as she says [in the chapter], her only disappointment with the song is that she didn’t make the argument plain or direct enough so that parents would be upset. Nobody seemed to be upset, and she was mystified that [‘White Rabbit’] became a hit.”

Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of a Bay”

Given that Redding’s been dead since 1967, Myers tracked down the song’s co-writer, legendary studio guitarist Steve Cropper to fill in. (He also interviewed three others for the song, including Booker T. Jones.) RealClearLife wanted to know what question Myers would’ve wanted to ask Redding were he still around to answer it. This is what he told us:

“Probably the [same] question that was on Steve Cropper’s mind: ‘What do you mean by the boats rolling on in?’ I never knew what the reasoning was behind that, and [when] we were talking, we talked about Otis being at Monterey and staying on Bill Graham’s boat. I said: Were you ever curious about what [Otis] meant? And [Cropper] said: That’s funny, I was having a hamburger up in Sausalito, and I saw the ferry turn sideways a little bit to create this roll to slow it down [before reaching the dock], and then suddenly realized what Otis meant by that.”

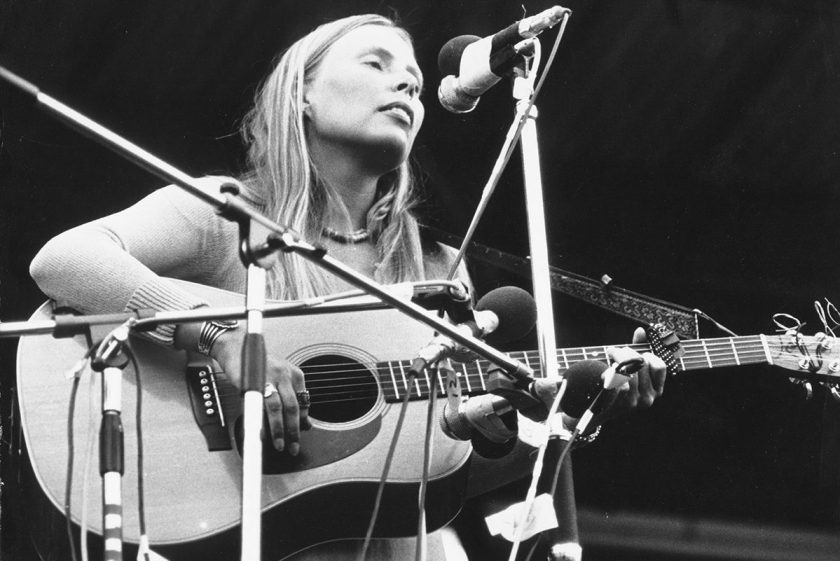

Joni Mitchell’s “Carey”

Myers flew out to L.A. in October 2014 to interview Mitchell about the track. He tells us he ended up spending two hours on her patio as she passionately recounted her “pre-planned trip” to the Grecian island of Crete, following her breakup with fellow rocker Graham Nash (of Crosby, Stills, and Nash fame). Here, Myers analyzes the song, “Carey,” which appears on the album Blue:

“This isn’t so much a breakup song as a ‘forget about him’ song. Because she’s not bemoaning the loss of anything; she is celebrating this quirky new person, this new character she met in Crete and the pros and cons of him and the experience of it. In that regard, it’s almost like song vérité—there’s a journalistic [quality] to this song when you know the story. She’s sort of reporting it out in music, explaining bits and pieces of it. When you hear the pounding of the waves in Crete and the caves and the bareness and the rawness of that kind of life with no comforts or facilities, it’s clear that a catharsis is going on. She’s leaving something behind, shedding her skin, and morphing into who she actually becomes. Instead of becoming someone who’s writing songs that [other artists] record, she goes into the studio and records Blue, and that’s really the start of Joni Mitchell as [the] artist we all know.”

Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues”

Myers talked to a number of musicians involved in the production of the song, including the core duo of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker. “[Aja] was like [their] White Album,” says Myers. “It had that anonymity. It’s about nothing and it’s about everything.” Below, Myers talks about the song’s fictitious main character, Deacon Blues, who dreams of learning the saxophone and breaking out of the “normal” life.

“You can almost say that [Fagen and Becker are] that guy [with the saxophone] in the suburbs. That’s exactly what Donald told me. He said: We related to that guy with the saxophone, who’s going to head out of town and determined to change his life and become a saxophonist. That was us; we grew up in the suburbs; that could’ve been us if we’d stayed there. [Fagen and Becker] were highly sensitive to the fact that that was their condition or that could’ve been their condition.”

To get the full scoop on a song’s anatomy, we strongly urge you to pick up a copy here.

—Will Levith for RealClearLife

Update: Additional edits have been made to Myers’ quotes for clarification purposes.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.