Want to know what the future holds? You need to meet the people building it. In our series Who’s Next, we profile rising stars of culture, tech, style, wellness and beyond.

Cruise. Crush. Concert. Childhood. What do these four words have in common? They all start with the letter C? That’s a pretty weak categorization. Words associated with “wave”? No, not that either.

Give up? Here’s the answer: “Life events that led Wyna Liu to become the editor of Connections,” the New York Times game that has become a daily obsession for millions around the world since launching in 2023. The category-matching puzzle doesn’t attract quite as many players as the pandemic-fueled juggernaut that is Wordle, but among the increasingly vital Games department at the Times, Connections has differentiated itself from the likes of the Mini crossword and Spelling Bee for one simple reason: it gets people fired up.

“I do feel like the feedback that I get skews on the angry side,” Liu said on a video call earlier this month from her apartment in New York City. “I get it. It’s like, I love being mad, you know what I mean? It’s fun to be mad.”

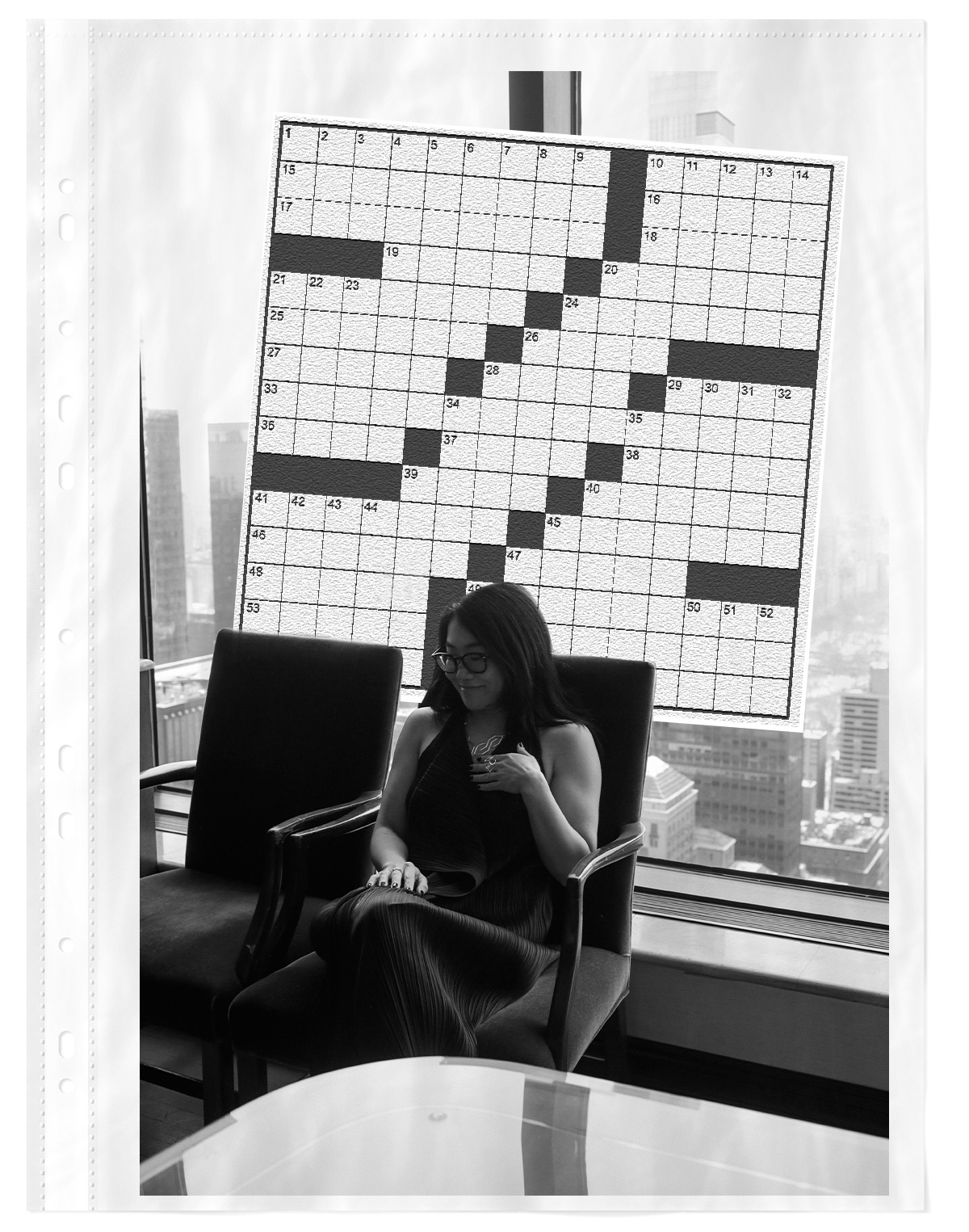

What’s there to be angry about? Aren’t the games, available online and in various Times apps, supposed to be an entertaining respite from the news coverage? If you’re asking that question, you’ve obviously never played Connections. The puzzle is simple enough in its gameplay: a four-by-four grid of words or phrases that you must sort into categories. But it’s Liu’s unique linguistic and relational machinations — playing with words, arranging the starting grid to misdirect, dreaming up bewildering categories — that have turned it into a sensation with staying power.

“It’s inherently very voicey,” explained Wyna (pronounced “win-ah”). “Words can spin off in so many different ways that the sort of curation, or the direction those go, are really based on the things that you like, things that are interesting, things that you think are funny.”

The unsaid subtext there — which she is unwilling to say herself, but that I have no qualms saying as an avid Connections player — is that Liu’s specific voice is the secret sauce.

I mean, who else would dream up the category “Words Misspelled in Nu Metal Band Names”? The words in that group were Biscuit, Corn, Lincoln and Stained. (“I feel like it’s of a time,” she laughed, “but that time happens to be my time.”) Or what about the December 29, 2023 edition? Literally no other puzzlemaker on the planet would have devised that one, as the starting grid is arranged in such a way that it references Liu’s own life. The second, third and fourth tiles in the top row are: Bad, Boy and Polo. Liu has an adopted pit-bull mix named Polo. “That was inspired by this,” she chuckled, lovingly ruffling him as he curled up behind her. “He can’t read, though.”

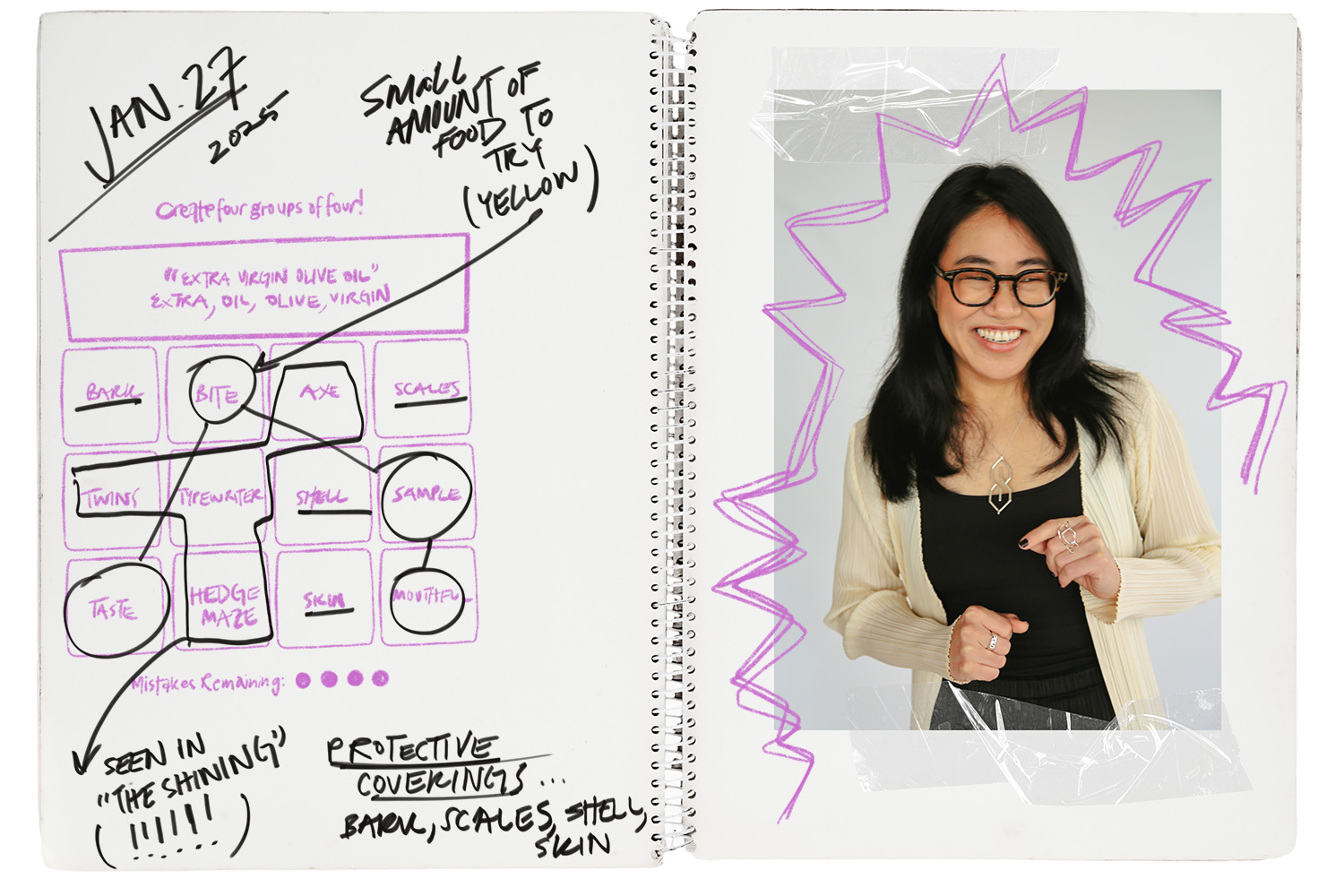

To be fair, those examples are all in good fun. The true fire underneath Connections, though, is stoked by the more dastardly categories. There was the January 27 puzzle that included “Extra Virgin Olive Oil” which grouped together Extra, Virgin, Olive and — you guessed it — Oil. (Yes, all your eye rolls did “trickle down” to her for that one, even though she’s not very active on social media.) Or the November 23, 2023 puzzle, which combined Glue, Gum, Tape and Stick under “Things That Are ‘Sticky.’” “People really didn’t like that one,” she laughed.

In the places where I’ve noted that Liu laughed about these puzzles, you might be picturing the maniacal guffawing of a puzzle wizard, accompanied by gleeful hand rubbing. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Her frequent giggles felt more like the product of giddy incredulity — the pauses in her answers seeming to say, how did I get here? How is it that my puzzles can make or break someone’s entire day? And more frequently than you’d expect, it’s the latter.

I do feel like the feedback that I get skews on the angry side. I get it. It’s like, I love being mad.

– Wyna Liu

Exasperated open letters to Liu — which usually take the form of diatribes or pleas for mercy — have become something of an art form in and of themselves. There’s the literal “Open Letter to Wyna Liu,” published at McSweeney’s, in which the writer admitted, “Those sixteen words haunt me.” (Many readers must have felt the same, as it was the sixth most-read story on the website in 2024.) The Atlantic called Connections “the most controversial game on the internet.” You can find daily entries in this canon posted on TikTok as well as the Connections subreddit, which boasts over 46,000 members.

One Redditor who failed to solve a recent puzzle after using up all three allotted mistakes had this to say: “I’m going back to bed.” See? Liu can — and will — break your day.

The Cruise (or Crush, or Concert, or Childhood) That Started It All

Wyna Liu doesn’t fit the mold — or should I say myth? — of a modern New York Times puzzle editor. Will Shortz, who’s been crossword editor at the paper since 1993, knew from the time he was in middle school that he wanted to make puzzles for a living. Joel Fagliano, the digital puzzles editor who’s also been helming the Mini crossword since its inception in 2014, was a senior in high school when his first Times crossword was published. As for Liu, she didn’t become “obsessed” with crosswords until after graduating from Oberlin with a degree in art, and it wasn’t exactly an interest in word games that sparked it.

“It’s a little embarrassing,” she said, this time with a deeper laugh and longer pause. “But I had a crush on someone who did the New York Times crossword. He worked at the chess shop. I would just stop by and be like, oh, you’re doing the puzzle? I started doing the puzzle.”

Varun Kataria Doesn’t Have a Master Plan, He Just Wants to Entertain You

After relocating a supper club from Wisconsin to Brooklyn, the New York impresario erected a roller rink down the street. As he says, “I’m just having happy stumbles.”But her infatuation — with puzzles — progressed from the Times to indie outlets like the AV Club Xwords (AVCX) to tournaments in New York where she furiously raced against other crossword solvers. Still, despite jumping headfirst into the everyone-knows-everyone world of cruciverbalists, she found herself clamming up once the puzzles were put away.

“I was always too shy to talk to anyone,” she said of her first years attending crossword tournaments. “I would go, solve, and then you could stay for pizza after, but I’d eat my pizza in a corner and I’d scurry home.”

Eventually, she found herself in a place where there’s no means of escape: a cruise ship.

In 2017, after she had gone to grad school and was working various part-time jobs, her globe-trotting mom got a brochure in the mail for the New York Times Crossword Crossing, a seven-night jaunt aboard the Queen Mary 2 from New York to Southampton in England. The trip promised an early copy of the crossword tucked under your door each night, mingling with 2,998 other puzzle fanatics and, most importantly, direct access to Times staff and contributors, including Fagliano, Natan Last, Deb Amlen and Ben Zimmer. “‘You love crosswords, I love cruises — there’s a crossword cruise,’” Liu remembers her mom saying. “‘Let’s go.’”

The Times sure got their money’s worth from that December 2017 sailing. Fourteen months later, Liu’s first crossword was published in the paper. Nineteen months after that, she was hired as a crossword editor. And last year? She was the driving force behind the astonishing 3.3 billion plays that Connections racked up. That’s over nine million puzzles being agonized over every single day.

While Liu credits the cruise with helping her get over her social anxiety at tournaments, and is thankful for the general camaraderie she found in the crossword community (“Everyone’s just a person that loves puzzles!”), she’s also quick to gush over the mentors who she says were instrumental in her moving up the ranks from puzzle solver to constructor to Times editor.

Most notably, there’s Erik Agard — whose crossword genius has been tapped by everyone from The New Yorker to, most recently, Apple News+ — who Liu met at a tournament and eventually helped her construct her first crossword ever. And there’s Ben Tausig, the founder and editor at AVCX, who Liu met through lexicographer (and Times cruise expert) Ben Zimmer when they all went to a Yo La Tengo show; Liu’s first published puzzle appeared in AVCX, and her first editing opportunity was there too.

“In many ways they have and continue to support me and so many other people,” she said. “I can’t say enough about them.”

It wasn’t until Liu was fully immersed in this world that she realized her mom contributed to her puzzle destiny in another crucial way — other than not tossing the brochure about the Times cruise into the trash. One day when Liu was visiting her parents’ house, she found an old stockpile of puzzle books that her mom had bought her as a way of entertaining an only child.

“It was this very sort of emotional moment where I was like, oh, of course,” Liu said. “You could see a direct line. This stuff was always there.”

“I would look at the bylines and was like, I know this person. These are people I really admire. These are the legends in the field and also some of my heroes and also some of my friends.”

How Wyna Liu Creates Discovers Her Puzzles

Liu still does crosswords. She contributes them to The New Yorker and edits them for the Times, but her job as puzzle editor at the latter is mostly taken up by Connections.

She’s far from a one-woman army. The elaborate Games apparatus includes, among other people, testers who tell her if the temperamental color-coded categories of yellow, green, blue and purple feel right (“If everyone’s like no, no, no, then I will make a swap”). But her quirks now feel inextricable from the puzzle. Yes, the gameplay is smooth and intuitive; yes, the design is seamless and distinctive; but it’s categories like “Synonyms for Rear End Minus Last Letter” that keep people playing. And the Times desperately wants you and everyone you know to keep playing.

So far, the Gray Lady’s proprietary puzzle formula seems to be working. In a time when most news organizations are trying every trick in the book to stem financial losses, the Times found in 2023 that “[p]eople who engage with both news and games on any given week have the best long-term subscriber retention,” according to Charlotte Klein’s Vanity Fair profile of the Games team.

I had a crush on someone who did the New York Times crossword. He worked at the chess shop. I would just stop by and be like, oh, you’re doing the puzzle? I started doing the puzzle.

– Wyna Liu

The beauty and moreishness of Liu’s creation, the thing that makes her version of Connections an ideal addition to an obsessively structured news organization’s income stream, is that it feels entirely separate from rote regimentation. Some days it’s ludicrous. Other days it’s hilarious. On the day I’m writing this, it’s devastating — I’m not too proud to admit that sometimes Liu’s puzzles are too perplexing for me to crack. An AI bot could never make the linguistic leaps that she consistently surprises us with. Neither, I think, could one of the puzzle phenoms who always seem to rise to the top in this particular community.

While Liu was hooked by the gold standard of crosswords and mentored by puzzlemakers who’ve made it their mission to help a wide swath of up-and-comers, she didn’t follow the standard path to get to her position as puzzle editor, and that has made all the difference.

I could point to Liu’s extracurricular art as the reason why her creativity is so well-suited to building Connections: She designs her own jewelry, takes neon classes, dabbles in knitting. Or I could point to her unorthodox combination of interests: She unwinds by doing yoga and watching horror movies (“I fucking love The Substance,” she said. Naturally, it inspired a board.) Instead, the real “aha” moment seems to have occurred when she was doing her grad school thesis project at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program in 2014. It was about the five Platonic solids, three-dimensional shapes whose faces are identical polygons.

“You discover shapes, you don’t invent them. There are these truths out there,” she said. “As our technology gets better, we can identify things that happen in nature that we didn’t know about. We didn’t make those, right? We’re learning about them. There’s something that’s really exciting and comforting and beautiful about that to me. So there is still the making of stuff, but the framework is not creating, it’s discovering.”

Instead of creating crosswords in the style of cruciverbalists who came before her, it feels like Liu is forging her own path with Connections. Melting down the standard meanings of words and sifting through what remains. Shaking the branches and deciphering the new patterns that phrases fall in. Plucking wild categories from God knows where.

Tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that, millions of people will attempt to solve her puzzle. And a small but vocal percentage of them will take to the internet to complain. It’s all part of the magic.

Now the real question: When is the Times going to organize a Games cruise so she can inspire the next generation of puzzle editors?

“I’m going to pitch that so hard,” she said. “I feel like the answer is probably no, but it’s not going to stop me from trying.”

Photography: Johanna Stickland for InsideHook