The last time Paul Thomas Anderson made a movie set in the 21st century, the 21st century had barely started. It was 2002: George W. Bush was president, Nelly had the No. 1 song in America and LiveJournal was the leading social networking destination. Punch-Drunk Love, a peculiar, lonesome sort of rom-com, arrived that fall, establishing Adam Sandler as a bonafide dramatic actor.

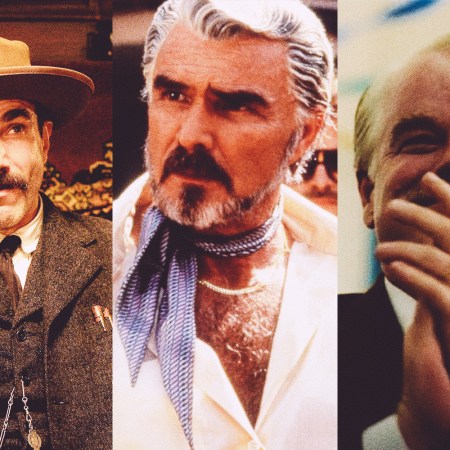

Anderson never made another film like it. Instead, for 20 years, he became America’s foremost crafter of period epics, centering his meticulous gaze on 1910s oil barons, postwar religious society, ’70s stoner-investigators, mid-century fashion milieu, and so forth. Anderson had an auteur’s eye for the hubris and rot underpinning 20th-century society —but our phone-addled, present-day world? It hardly seemed cinematic anymore.

In the decade or two following Punch-Drunk Love, as society hurtled past some invisible threshold of digital derangement, the most prestigious and prominent American filmmakers seemingly gave up on making movies about contemporary life. Of the 10 movies that won Best Picture during the 2010s (that is, from The Hurt Locker to Green Book), all but one were period pieces set sometime before 2005. History marched on, but Hollywood’s preoccupation with the past made it feel like the silver screen had reached some “End of History?” purgatory.

All of which makes One Battle After Another — Anderson’s latest film, and first to reckon with a country cracked open by neo-Nazis, ICE raids and Trump’s vice grip on American democracy — that much more exhilarating. The filmmaker loosely adapted Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, a postmodern novel published in 1990 and set in the Reagan ’80s, but chose to transplant it to the modern era, an authoritarian milieu not so different from Trump’s second term, a world of cruel immigration raids and community-run mutual-aid efforts. It feels chillingly current, a strange achievement for a filmmaker who’s made his name directing lavish historical epics.

The success of One Battle After Another, an early Best Picture frontrunner, could rouse Hollywood’s most prominent directors from their historical haze. Anderson couldn’t have known the film would arrive, eerily on time, eight months into Trump’s return to power and ICE’s subsequent assault on civil liberties. Yet it also arrived in tandem with a wave of high-profile, auteur-driven films that explicitly and unapologetically confront life in a fractured, post-Trump America — films like Ari Aster’s Eddington, a caustic, COVID-set satire, or Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia, an absurdist black comedy laced with brain-pickling conspiracy paranoia.

They don’t all succeed on the level of One Battle After Another (I’ll admit I tried and failed to get on Eddington’s level), but they complement Anderson’s portrait of a nation coming unglued.

Here, finally, is a year in which some of the most talked-about American movies weren’t just made in the 2020s but feel distinctly of the 2020s, the way paranoid thrillers like Klute and The Conversation felt distinctly of the 1970s. Is it any wonder the onscreen vibes are, by and large, bad?

“One Battle After Another” Is Just as Good as Everyone’s Saying It Is

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film is his best to dateWell before the pandemic accelerated society’s descent into tech-fueled isolation and polarization, Hollywood’s foremost American auteurs seemed to lose interest in depicting the present onscreen. Martin Scorsese hasn’t made a narrative film primarily set in the 21st century since 2006’s The Departed; Quentin Tarantino hasn’t done so since 2007’s Death Proof. Until recently, Anderson hadn’t since Punch-Drunk Love. And Steven Spielberg has favored dystopian futures and the distant past over depictions of the measly present.

Of course, the strongest period films can, and often do, deliver oblique comment on the periods in which they were made. Set during the Holocaust, Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023) proved chillingly applicable to the season of genocide in which it was released. And Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) wasn’t subtle in its indictment of technologists who disregard the moral consequences of their creations.

Gradually, the establishment’s retreat from contemporary stories yielded an opportunity to younger and nimbler filmmakers. Future generations curious about life in the 2010s or early 2020s could learn plenty from the Safdie brothers’ anxiety thrillers or Jordan Peele’s subversive horror-satires or Kelly Reichardt’s minimalist portraits of life on the margins or Radu Jude’s caustic class satire, or even the “Screenlife” films that brought horror into the digital realm. You could make a great movie on an iPhone, as Sean Baker did with Tangerine (2015), and you could make a great movie from a Twitter thread, as Janicza Bravo did with Zola (2021).

Still, by the early 2020s, I had grown frustrated with Hollywood’s unwillingness to portray or even acknowledge the pandemic in cinema, as European directors, such as Claire Denis or Joachim Trier, have more readily done. In a 2023 essay for the Guardian, I argued that filmmakers “filmmakers ought to acknowledge the pandemic’s ongoing toll as a backdrop for fictional storytelling.” An unpopular opinion? Sure. But ignoring it felt like a kind of cultural denial.

So when Eddington arrived in theaters last summer, I admired Ari Aster’s audacity but also wondered if I’d made a wish on a monkey’s paw. Once a horror wunderkind, Aster now has turned his attentions to the real horror: American culture wars. Eddington, his nerve-touching neo-Western, transplants viewers into that tempestuous summer of 2020, when COVID lockdown coincided with the Black Lives Matter uprising. Aster’s film uses these events as the backdrop for a dispute that spirals out of control between a brooding, anti-woke local sheriff (Joaquin Phoenix) and a cringe-liberal mayor (Pedro Pascal).

All the terror and misanthropy of Aster’s horror hits are there, but not enough comic timing. In its claustrophobic unraveling, Eddington circles around some interesting ideas about how people’s politics are often driven by petty personal resentments and pathologies more than larger principles. But there’s a smugness and nihilism to the writing that I found tiresome. Aster wrings comedy out of lampooning low-hanging fruit like anti-maskers and anti-racist teens, but the heavy-handedness is suffocating. Every major character feels like a stand-in for some political subset; every confrontation telegraphing “This Is About the State of America Today.”

Still, Aster deserves some credit for burrowing deep into a stretch of recent history — peak COVID — that most directors of his prominence wouldn’t touch. What Eddington gets right about life in 2020 and beyond is that smartphones feel like weapons when every altercation is livestreamed or posted or made into viral fodder. As the critic Corey Atad observed, “In Eddington, everyday human social dynamics are mediated and perverted by the screens that refract them. Eventually — inevitably — these dynamics explode into violence.” Or, as Aster himself described it, the film is “a Western, but the guns are phones.” That message is rammed home by a climactic shot in which a young, Kyle Rittenhouse-esque activist guns down an Antifa terrorist with his right hand while livestreaming with his left.

Similar ideas marinate more satisfyingly in Bugonia, Yorgos Lanthimos’s pitch-black comedy about two isolated young men (Jesse Plemons and Aidan Delbis), hopped on conspiracy theories, who kidnap a high-powered pharmaceutical CEO (played with vitamin-popping girlboss zeal by Emma Stone) because they think she’s an Andromedan alien primed to destroy the human race. A faux-triumphant score from composer Jerskin Fendrix underlines the absurdism in intermittent bursts.

Like Anderson, Lanthimos is best known to mainstream audiences for directing Oscar-winning period pieces (The Favourite, Poor Things) set in the distant past. Now he circles back to our troubled modern age. Like One Battle After Another, Bugonia draws from decades-old source material (in this case, the 2003 film Save the Green Planet!) but shifts the story to the present-day, a savvy adaptation choice. The Plemons character obsessively studies YouTube videos about alien races and instructs his cousin (and co-conspirator) in chemical castration as a means of avoiding “distractions.” The Stone character sings along to Chappell Roan in the car and fluently speaks the language of post-Lean In corporate jargon to try to persuade her captors to release her because she is a “high-profile female executive.”

In other words, Bugonia is laced with dark humor and paranoia, but it also functions as a grim parable examining how grief, isolation and economic alienation can contribute to radicalization in young men, triggering bizarre acts of violence. Today’s Travis Bickle is as likely to wield a YouTube channel as a gun. In recent years, conspiracy-addled young men have done crazier things than abduct a CEO.

The film’s outlandish and twisty final act won’t leave you with much hope for the future of humanity. But it did leave me with hope about cinema’s capacity to convert the extremely online hellscape of modern life into mordant comedy.

Looking Back at a Decade of Iconoclastic Director Yorgos Lanthimos

Lanthimos is proof that the movie industry isn’t always brokenA miraculous thing about One Battle After Another is that it is both Anderson’s most politically charged film by a mile, and perhaps his most personal. Which is not to say that he’s a revolutionary by any stretch, but a white father reckoning with the shortcomings of his generation and trying to keep his multiracial children safe in a country overrun with white nationalists and racial violence.

In a jittery, stoned-to-the-gills performance that ranks among his all-time best, Leonardo DiCaprio portrays Bob Ferguson, a washed, former revolutionary, long removed from his glory days with a radical group known as the French 75. As the film’s heady first act leaps 16 years forward, into some alternate semblance of present-day America, Bob is living in hiding with a teenage daughter (Chase Infiniti), whom he must rescue from the clutches of a sadistic military colonel (Sean Penn), a repugnant creep who presides over fascistic immigration raids. Ten years ago, this would have resembled a faintly dystopian setting; today, it just looks like our national normal.

In more domestic scenes, it’s interesting to see Anderson write dialogue that reflects the generational clash between Zoomer teens and Gen X parents. In one sharply funny exchange, Bob asks his daughter, Willa, about a nonbinary friend’s pronouns, and she blurts out in frustration: “It’s not that hard! They/them!” What is One Battle After Another if not a movie about being an out-of-touch Gen X dad? Elsewhere, Anderson resolves the problem of depicting iPhones onscreen with a clever solution: Bob refuses to use smartphones because he’s paranoid about the government surveilling him, and because he’s a wacked-out stoner who’d rather get high and numb his frayed nerves. (Of course, Willa disregards her dad’s orders and has a secret phone.)

Bob is, in other words, living off the grid; he’s stuck in the past, disconnected from the activism and resistance efforts happening around him. During my second viewing, it occurred to me that the movie’s 16-year time jump strangely mirrors the filmmaker’s own surreal journey into confronting present-day America in film.

Hear me out: Bob, like PTA, is a guy who’s perpetually ensconced in long-ago history — a guy who’d rather watch The Battle of Algiers than monitor current events. Like Bob Ferguson being roused from his stoner haze by a single alarming phone call, Anderson has also been whisked out of his fixation on the distant past and forced by urgent circumstances to grapple with the terrifying realities of the present. One Battle After Another depicts the difficult work of reengaging with the world around you, reengaging with the on-the-ground activists and mutual-aid workers, embodied by Benicio del Toro’s indefatigable Sergio St. Carlos, doing the gritty work of organizing against fascism.

And engaging with the technological realities of the 21st century. It hardly seems a coincidence that the final scene depicts Bob’s character reclining on a couch, clumsily figuring out how to work an iPhone — a piece of technology that is nearly 20 years old and yet has never appeared in a PTA film before now. Willa gives him tips. Father and daughter have reunited and reconnected, and after he shows her a letter from her absent mother, Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), she darts off to attend a protest three-and-a-half hours away, in Oakland.

“Be careful!” Bob shouts after her, finally snapping a functional selfie, and checking his own curmudgeonly paranoia. Coming from the guy who brought us the bowling-alley finale of There Will Be Blood, it is a disarmingly optimistic ending. You sense that Anderson made this film, with its satire of post-revolutionary fatherhood, for his kids, and so Willa’s heroism can’t crumple into despair. Maybe that’s what makes One Battle After Another more galvanizing than Eddington or Bugonia or Tár or any number of ambitious films about How We Live Now — this one stares down fascism, white supremacy and dehumanization and still manages to summon a glimmer of hope.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=450%2C450)

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=750%2C500)