Danny Kirwan was able to translate the weight of everyday sadness into a song.

A winter-stripped tree seen through a windowpane spotted with ghost-like drops of moisture. The fear that the Night Bus will never come. The never-ending aftershock of the moment you realized your parents would not live forever. A northern city on a damp and cold Sunday evening as the streetlights flickers on, but there is no life to light. The awareness that the sun, dimmed by coal smoke-colored clouds, will one day turn into cold stone and every grain of man’s achievements will be eternally forgotten.

Danny Kirwan sang and played guitar for Fleetwood Mac between 1968 and 1972.

The treasured love letter, the ink blurred by rain and lost forever. The perfect moment split by the wrong word. The memory of the warm glow of an old radio, never to glow again. The intense, humming weight of the silence you felt as a child in the moment after you heard a beloved grandparent had died. Looking at the radioactive blue moon and knowing that everyone you love who is far away sees the exact same moon.

Very few artists put this everyday sadness into song. Those who do, well, these are our saddest saints, and we celebrate them; they usually do not fade into the cold fog of time that their sad-happy art seemed to predict. But this was the fate of Danny Kirwan.

Fleetwood Mac was formed in 1967 by guitarist and vocalist Peter Green, who soon drafted in guitarist/vocalist Jeremy Spencer, bassist John McVie, and drummer Mick Fleetwood. The 1960s’ Fleetwood Mac bore little musical resemblance to the band that achieved megastardom in the mid-1970s: The original Fleetwood Mac morphed Chicago Chess Blues and Delta blues with early rock’n’roll primitivism to produce an incendiary but skilled and lyrical sound that anticipated heavy metal, punk, the tight-but-loose Anglo-American snort of Led Zeppelin, and even aspects of glam. It’s no accident that bands as diverse as Judas Priest, Santana, and the Rezillos famously covered early Fleetwood Mac songs.

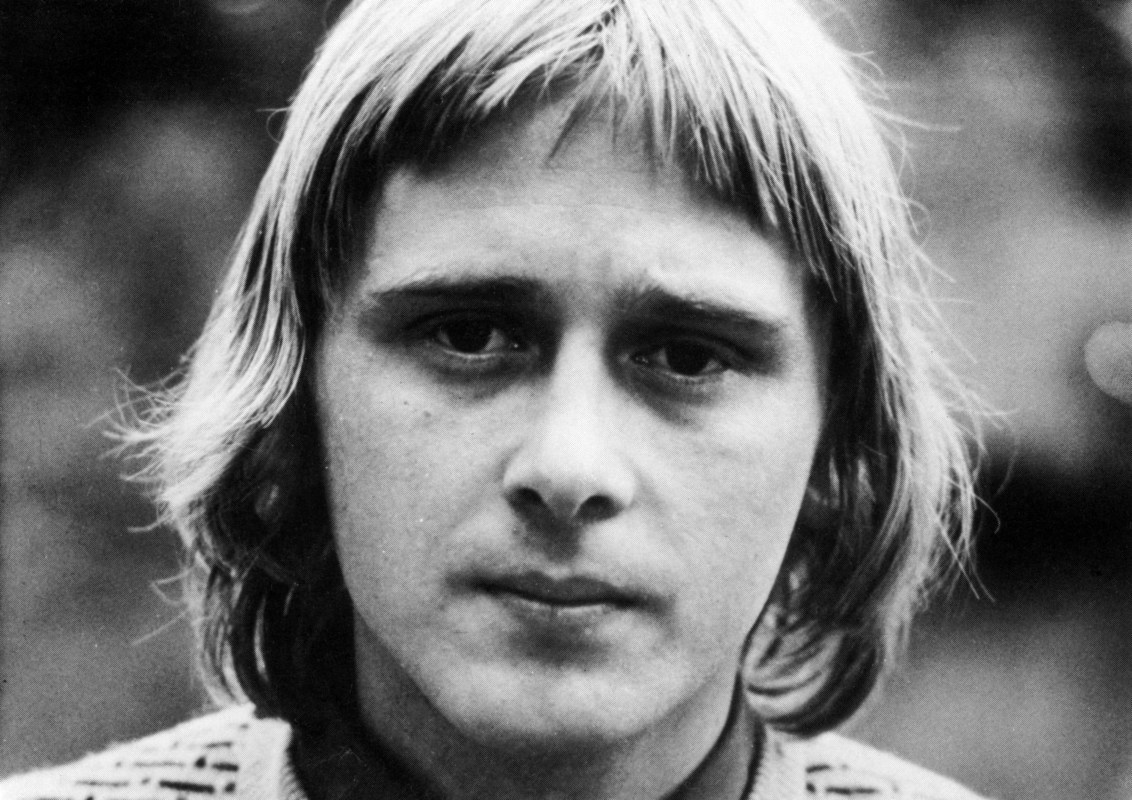

Danny Kirwan joined Fleetwood Mac in 1968 when he was just 18. He was doe-eyed, blonde-banged and pretty; he looked more like a mod ingénue than the hard-jawed and wild-haired men who already comprised the Mac. Right away, Kirwan introduced a sensitivity, melancholy and hypnotic melodicism to the Mac sound. His influence is evident from his first moments in the band: on their massive English hit single, the instrumental “Albatross,” Kirwan plays a sighing, tremolo’d rhythm/solo melody that sounds halfway between Santo and Johnny and Vini Reilly of the Durutti Column. It is (very much) worth noting that “Albatross” in general (and Kirwan’s sensitive, spectral playing in particular) was an enormous influence on George Harrison, and the Beatles’ song “Here comes the Sun King” owes a great, great deal to “Albatross.”

Within a few years, Fleetwood Mac had shape-shifted enormously, allowing for Danny Kirwan’s emotionally vivid talents to shine. By 1971, Green and Spencer were gone, virtually eliminating the blues, R’n’B, and rockabilly elements that had defined the early Mac; and in 1970 Christine Perfect joined, bringing along her intense and expressive alto and emotionally resonant songwriting. Perfect (soon to be Christine McVie) was a magical foil for Kirwan.

By Future Games (1971) and 1972’s Bare Trees, Danny Kirwan was regularly producing enchanting and poignant music in Fleetwood Mac. His songs (which were often instrumental) were sepia-toned but sweetly melodic and had an extraordinary lonely-beach-in-winter quality. Mixing opium-scented arpeggios with a (very) gentle effect of the blues and simple, sweet/sad Nico-esque melodies, virtually all of Kirwan’s preciously beautiful Mac material reaches into your chest and cradles your heart.

I would especially direct you to “Sunny Side of Heaven” and “Dust” from Bare Trees; the extraordinary chime and resonance of “Woman of a Thousand Years” from Future Games (with its Kirwan/McVie close harmonies and gentle but persuasive pop feel, it may be the first “modern” Fleetwood Mac song); and “Earl Gray” from 1970’s Kiln House (which sounds a bit like Cream’s “Badge” played by R.E.M. if they had smoked a lot of hash and were really, really sad).

Danny Kirwan’s music in Fleetwood Mac is, consistently, a cloak of crystal melody emerging from a cloud of sadness.

In the monumental span of rock and pop, our strange era full of superstars and superfools, victims and beasts, the angelic and the ridiculous, I see Danny Kirwan’s beautiful, sad, and mysterious figure casting an enormous shadow in two very important places:

Danny Kirwan needs to take his place alongside our heroes of the elegiac tragic, the masters of autumnal, bittersweet, heart-heavy rock and pop. That is, he needs to be spoken of in the same treasured, measured breaths in which we talk about Elliot Smith, Jeff Buckley, Tim Buckley, Syd Barrett, Nick Drake, and Alex Chilton. Although Kirwan’s catalog is small and almost open-ended in its incompleteness (his career feels like a beautiful paragraph in a book you’ve just started, but then you drop the book in a puddle of muck on the subway platform), it has a gravity and timeless charm that tells you that this is someone very, very important, indeed.

Secondly, Danny Kirwan (alongside Christine Perfect) essentially created the modern Fleetwood Mac, midwifing the transition of the band from a group rooted in rockabilly and blues to a one that played accomplished and melodic pop with a slightly dark edge. True, some would give a little of the credit to Bob Welch (who was one of Mac’s composers and vocalists from 1971 to ’74); but I actually see Welch, who specialized in a very early/mid ‘70s kind of FM/West Coast pop, as an outlier: The spirit and sound Kirwan and Perfect brought to the band—hummable, proto-shoegaze pop songs with a dusting of melancholy—essentially became the model for Mac’s platinum future. Echoes of Kirwan’s spirit and innovation (there is something happy here and there is something dark here and guitars chime and you can sing along) are literally all over Mac’s two breakthrough albums, Fleetwood Mac, and Rumours.

Danny Kirwan left Fleetwood Mac in 1972. He was only 22. What should have been a bright future dissolved into a very slow, sad, and mysterious fade? Although Kirwan released solo albums in 1975, ‘76, and ‘79, these records are shadows of his former skill and originality, almost bizarrely unattached to the graceful, grave, and heart-wrenching music he made as a very young man in Fleetwood Mac. After the release of his final, awful, and emotionally and musically detached solo album in ’79, Danny Kirwan became, almost literally, a ghost: He virtually vanished into poverty, mental illness, addiction, and homelessness. It is arguable that no (relatively) well-known pop/rock performer disappeared from the public eye as thoroughly as Kirwan did; he made Syd Barrett seem like an extrovert. There appear to be no photos of Danny Kirwan after 1993, virtually no accounts of encounters with him after 1998, and it seems he spent his final decades either homeless or living in a shelter/hostel, far, far away from his former fame.

But his long, confusing, and heartbreaking denouement must not obscure the poise and significance of his enormous achievements between 1968 and 1972. Virtually every note Kirwan played during that time rings with grace, pain, and a nearly unique ability to communicate his hurt, hope, and unanswered questions via the electric guitar and a wistful, whispering voice.

Danny Kirwan needed something from the world that the world could not give him; but he gave us an almost pure expression, via sound, of his search. I hope he finds the answers and the peace in his future voyages that eluded him during this one.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.