If there’s one thing we can all agree on these days, it’s that we love our data—and nobody loves it more than scientists. Looking to figure out why some scientists have successful careers, in analyzing a cross-section of the industry, researchers determined that age has no bearing on one’s odds of success.

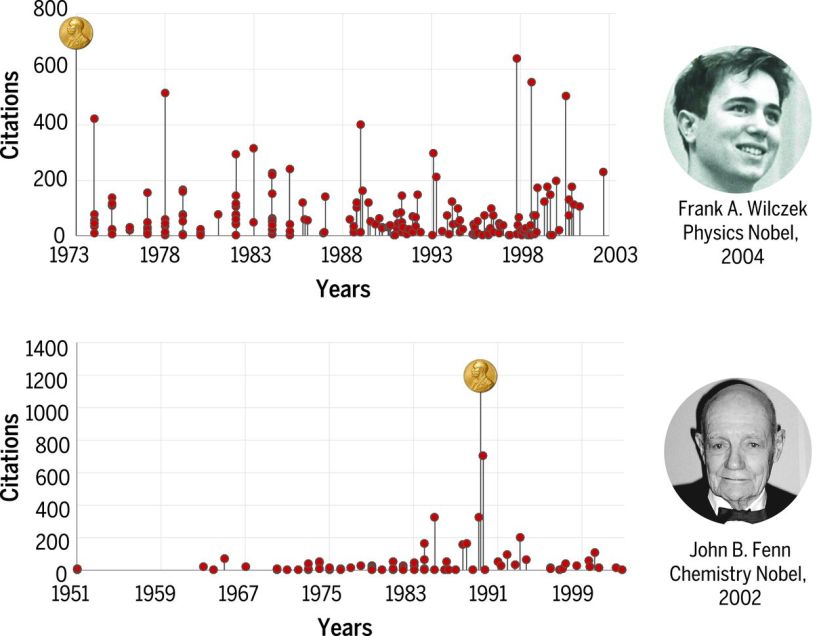

In the study, whose results were published in November in Science Today, researchers reviewed the publications of 2,887 physicists, as well as a blend of career profiles and data from online research platforms Google Scholar and Web of Science, respectively. Given that success in the sciences is determined largely by the influence of a scientist’s publications, the researchers were trying to locate patterns in the timing of a scientist’s highest-impact papers. It turns out there were none. In fact, the timing is entirely random.

That said, the process of scientists creating high-impact studies is far from arbitrary. Through their findings, the group of researchers created a model to pull back the curtain on the role of luck and productivity in one’s career. While the markers for future success were specific to each individual, the study claims its model can be used to predict when a scientist will enjoy future achievements. Even more impressive, the researchers say they can do it using just 10 papers.

The prediction is based on what the group called the “Q Value,” a metric factoring in the number of publications produced and the amount of citations given, thus determining the consistency of a scientist’s impact. This means if the Q Value of a biologist (or any other “-ist,” for that matter) were low at the beginning of his or her career, then the individual would likely never produce any high-impact research.

There are two things to keep in mind, though: First, the study doesn’t articulate what determines somebody’s Q Value, since the scientists don’t know (they only calculated for it); and second, an individual’s Q Value is not necessarily an indication of their scientific prowess, only the impact of their studies.

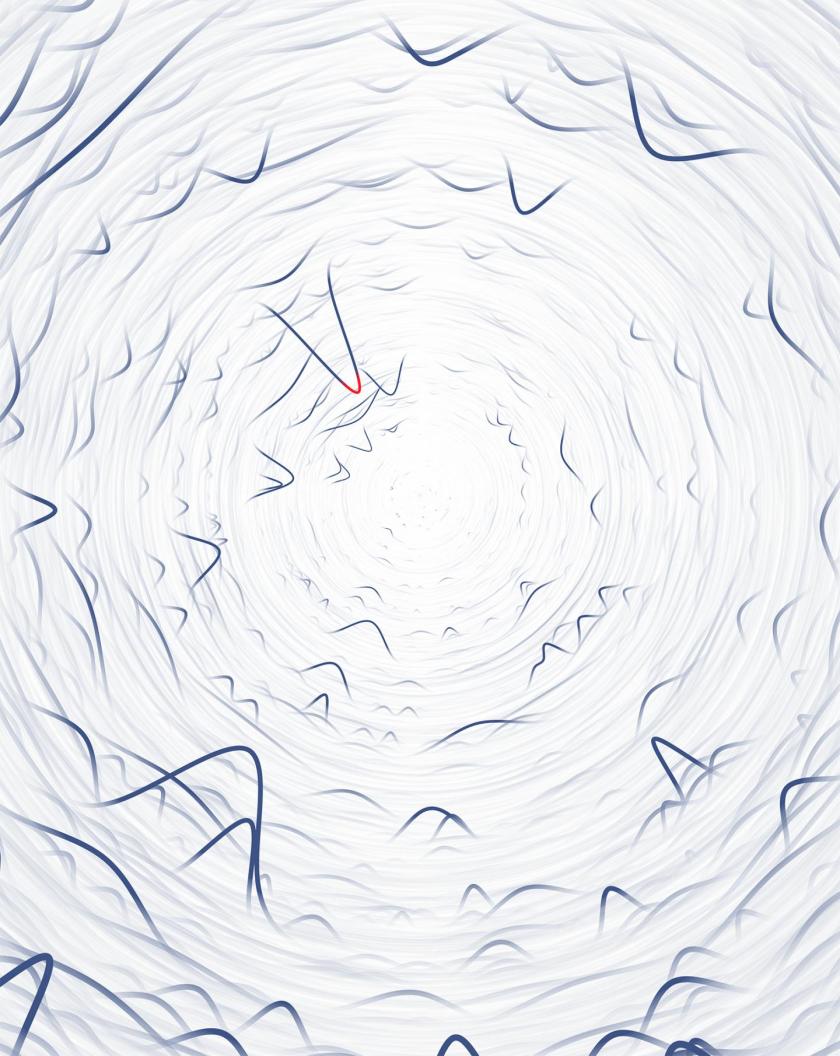

The researchers created a website that visualizes the career path of those scientists that were studied, and for lack of a better word, its “psychedelic” (see example below). View it by clicking here.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.