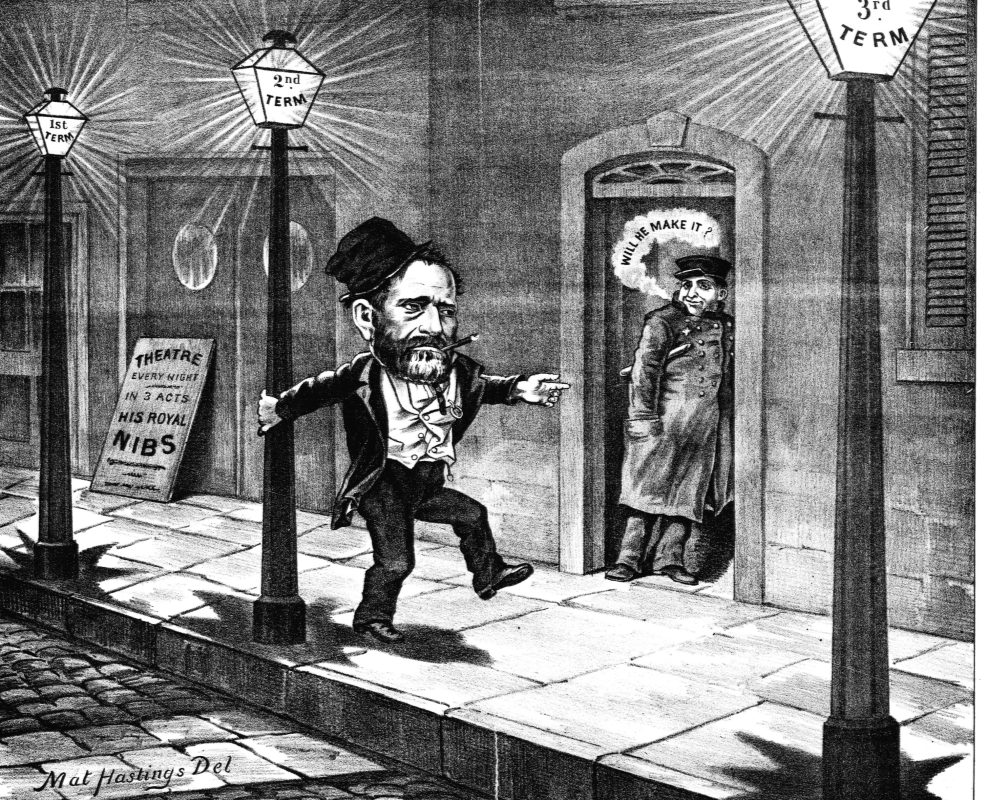

Victor in the bloodiest conflict in American history. Twice elected President, where he crushed the Ku Klux Klan. Author of one of the most celebrated works ever produced by this nation. This is the resume of Ulysses S. Grant. Yet you may think of him as a drunken butcher who went on to become an incompetent commander-in-chief. Even his champions often wind up dwelling on his perceived flaws, as when President Trump saluted Grant’s military acumen but noted contemporaries generally saw him as a man with a “drinking problem,” an “alcoholic.”

The result is that the name “Ulysses S. Grant” has survived, but it’s become attached to a person who barely resembles the actual article. Among the major distinctions:

Grant’s Primary Lifelong Addiction Wasn’t Alcohol. Grant had one obsession throughout his life: horses. As a boy, he preferred their company to people. Horsemanship was one of the few areas he truly excelled at West Point, setting the Academy high-jump record. A 1956 Sports Illustrated article “Horses for the General” noted that Grant displayed a “genius” for breaking difficult horses. His methodology was surprisingly tender: “If people knew how much more they could get out of a horse by gentleness than by harshness, they would save a great deal of trouble to the horse and the man.”

Grant was a freakishly skilled rider. Ron Chernow’s massive 1,074-page book Grant heavily covers his abilities with horses, reporting that as a boy he preferred not to bother with stirrups or saddles and amused himself by “riding at top speed by age five while standing one-legged on its back.” (Yes, that’s what he was doing at five.) A fellow West Point student said it was “as good as a circus to see Grant ride.” Even in the White House, Grant was busted by the police for racing his horse through the streets. Quite simply, Grant was happiest engaged in feats that would cripple lesser riders.

You can’t be an elite horseman and hammered out of your skull simultaneously—not for long, anyway. Did Grant drink, including at times to excess? Absolutely. But Grant tended to struggle only under very specific circumstances.

Grant Drank Not From Stress, But Sorrow. In time, Grant’s inner circle came to include some non-horses. It was always a small one, however—the core was his wife and children. Making it crushing that his initial military service from his 1843 West Point graduation to his 1854 resignation (more on this shortly) saw him separated from them for years at a time.

Despite starting out as a quartermaster and handling supplies, Grant experienced and ably handled combat during the Mexican-American War from 1844 to 1846. Peace, however, often proved overwhelming. He lost the sense of purpose that came with the conflict and helped him forget he was alone. Struggles with migraines and depression didn’t help. Grant occasionally engaged in binge drinking as a coping mechanism.

Particularly with his later reputation as a “butcher,” it’s easy to picture the combat-hardened Grant with a few drinks in him turning into a lunatic ready to take on the town. In fact, drunk Grant was oddly consistent with the gentle boy hanging out with the horses. Chernow notes alcohol reduced Grant to a “babbling, childlike state.” Imbibing may have hit him harder than most because he was relatively small: at most 5’8”, under 140 pounds. Everything finally fell apart in 1854 and Grant resigned from the Army in California to rejoin his family in the Missouri.

A belief lingered that Grant’s imbibing had driven him out of the military. Grant insisted this was untrue and he simply wanted to go home. In his Memoirs, he wrote he resigned because he “saw no chance of supporting [his family] on the Pacific coast out of my pay as an army officer.” Whatever the case, Grant’s alcohol consumption had clearly become a problem and he once admitted “when I was on the coast I got in a depressed condition and got to drinking.”

Rumors of renewed tippling would plague Grant the rest of his life. President Lincoln did his best to ensure that Grant remained on the wagon, having his wife Julia travel with him when possible. (Famously, on October 30, 1863, the New York Times reported: “When someone charged Gen. Grant, in the President’s hearing, with drinking too much liquor, Mr. Lincoln, recalling Gen. Grant’s successes, said that if he could find out what brand of whiskey Grant drank, he would send a barrel of it to all the other commanders.” It’s a classic remark, but one Lincoln denied making.)

It appears Grant’s slips were just that: slips. When occupied either by a pressing task or his loved ones, he invariably stayed sober. One of his lapses appears to have occurred after the Civil War when Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, ordered Grant to travel with him on a speaking tour lasting three weeks and covering 2,000 miles. Separated from his family and used as little more than a prop by a man he neither agreed with nor respected, Grant seems to have begun to drink before finding an excuse to leave the trek early.

This was Ulysses S. Grant—a small, rather shy homebody who often struggled with day-to-day life yet possessed an unnerving poise under pressure. (Again, think a five-year-old standing one-legged on a running horse.)

Why Grant Matters. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel Tender Is the Night refers to Ulysses S. Grant working in a general store in Galena, waiting for the call of “an intricate destiny.” If the Civil War hadn’t occurred, it’s uncertain what the future would have held. From a professional standpoint, Grant didn’t handle civilian life much better than his peacetime military one. For a time he was reduced to selling firewood on the streets of St. Louis. He generally proved to be kind but financially incompetent, notably when he purchased a slave in an apparent business plan only to abruptly emancipate the man. (A noble sentiment, except he was already desperate for money.)

Yet war brought out something extraordinary in Grant. Much like the child riding so fearlessly on bareback, he was almost unnaturally poised during combat. (This was essential to the Union, which had been plagued by disastrous retreats ever since the First Battle of Bull Run.) He also had a gift for envisioning the big picture. Whereas many generals fixated on winning individual battles, Grant thought of entire campaigns. He wanted to capture armies, not places, because when you took out an opponent you reshaped the entire conflict. Thus when Grant won the first major victory of the Civil War for the North at Fort Donelson in 1862, he demanded “Unconditional Surrender.” (And yes, this did give “U.S.” Grant a seriously great nickname for the rest of his life.)

The result was a remarkable rise through the ranks. Returning to the army following the Confederacy’s April 12, 1861 attack on Fort Sumter, by June he became a Colonel. By July, he was a Brigadier General. On March 9, 1864, Lincoln put his full faith in Ulysses S. Grant, making him the Lieutenant General of all Union Armies.

Just over a year later, Lee surrendered.

With the Union‘s larger population and greater resources, it’s easy to regard victory as inevitable. That wasn’t the case. The Confederacy didn’t need to win—it just had to survive. An indefinite stalemate could have drive the people of the North to demand peace. Lincoln could have easily lost his 1864 reelection bid, leading to a government inclined to settle rather than continue the struggle. Brilliant as he was, Lincoln had a tendency to pick commanders even he wound up mocking. (Most famously, after yet another military disaster, he quipped, “Only [Ambrose] Burnside could have snatched one more defeat from the jaws of victory.”)

Then Lincoln found Grant. While his predecessors had stalled and struggled, Grant won. And he did so in a surprisingly efficient fashion. Counting killed, wounded, missing, or captured soldiers, Grant’s forces suffered roughly 154,000 casualties while inflicting 191,000. Beyond this, he brought the Civil War to an end with a speed unimaginable to those who preceded him. Twice as many soldiers died during the Civil War from disease than battle wounds. By finally bringing peace, Grant unquestionably saved both Union and Confederate lives.

While critiques can certainly be made of decisions by Grant (particularly within battles), his overall results are nothing short of remarkable. His presidency would be far more blemished, but with one genuine achievement.

A Flower in the Mud. Prior to the Civil War, Grant had not excelled at life in peacetime. That never really changed, particularly after he became president in 1869. Even Grant acknowledged as much, beginning his eighth and final message to Congress with the hilariously humble announcement:

“It was my fortune, or misfortune, to be called to the office of Chief Executive without any previous political training. From the age of 17 I had never even witnessed the excitement of attending a Presidential campaign but twice antecedent to my own candidacy, and at but one of them was I eligible as a voter. Under such circumstances it is but reasonable to suppose that errors of judgment must have occurred.”

Grant’s terms were too often marked by selecting friends who should not have been in office and blindly supporting them. To cite one example: Grant’s personal assistant, the former Union general Orville Babcock, was a member of the “Whiskey Ring” defrauding the government of millions of dollars in taxes on whiskey. Grant defended him at every turn, but Babcock eventually had to step down. (In a cruel irony, Babcock managed to get a new government job as a chief lighthouse inspector, only to drown while performing his duties.)

Yet Grant also performed a vital service to the nation. As President, he took on the Ku Klux Klan. It was a necessary task. His predecessor Andrew Johnson despised blacks, both when they had been slaves and particularly once they were free. He did his best to ensure the fallen Confederacy held on to power. Thus thousands were murdered throughout the South, with the Klan often responsible for the violence. In response, Grant supported and signed laws known as the “Ku Klux Klan Acts” in an attempt to ensure received blacks equal protection under the law. The Klan was soon largely broken—they wouldn’t rise again until the 1920s.

There is much to want to forget about Grant’s overall presidency. But he has an achievement worth remembering, which sets him apart from many of our former leaders.

Grant’s life ended with a final remarkable display. In a sad bit of proof that his administration’s corruption had been due to his obliviousness as opposed to his personal greed, Grant wound up being swindled and bankrupted. Beyond this, he was dying of throat cancer. Seeing only one way to provide for his wife, he agreed to write his autobiography and raced to finish it. (It was published by Mark Twain, but all evidence suggests Grant did the writing himself.) He finished it a week before his death on July 23, 1885 at the age of 63. Personal Memoirs proved a financial success but more importantly has stood the test of time as a classic. The Guardian ranked it 55th of its 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time list in 2017, calling it “the gold standard for presidential memoirs” and a work both “intimate and majestic.”

So why has Grant’s standing slipped so severely? There are two key reasons:

–Lost Before Lincoln. In life, Lincoln cast a long shadow, literally and in every other way. It only grew with his death, as he was martyred at his moment of triumph. (Grant famously turned down an invite to go to the theater with Lincoln—for the rest of his life he blamed himself for Lincoln’s death, feeling he could have stopped it.)

Lincoln’s assassination ensured even his fiercest critics came to champion him. Coupled with his timeless eloquence, Lincoln soon overshadowed all others involved with the Northern effort, including the general who finally gave him his victory.

The real damage, however, came from those who couldn’t best Grant on the battlefield, but could sully his name after death.

–The South Rises Again (and Drags Down Grant). For many, Robert E. Lee has come to be seen as the embodiment of dignity and honor. This is, at best, a questionable conclusion. Lee was a slave owner and often a brutal one, using whippings as punishment and quick to separate families by hiring members off to other plantations. If you’re an American, Lee’s also something else: A traitor. After all, he was a member of the U.S. military who elected to take up arms against the nation he served—this is the very definition of treason. (Indeed, President Andrew Johnson wanted to punish him for that offense—Grant had to intervene personally and threaten to resign to save Lee.)

Lee himself seemed to want the Confederacy to be forgotten, writing in 1869: “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelings engendered.”

Yet the beginning of the 20th century saw a rise in support for Confederate heritage (and, with it, a return of white control of the South). Statues of Confederate icons began to pop up everywhere, notably in the U.S. Capitol. With this also came a rewriting of history through works like Birth of a Nation, insisting that the Klan arose to “protect” Southern virtue, not to terrorize recently freed slaves into subjugation.

And who was the leader of these barbarians? Well, Lincoln had achieved saintly status, so it must have been… Grant. A butcher. A drunk. A man who used raw numbers where Lee relied on courage and strategic genius. Leading to the rise of Lee and other Confederate leaders and the decline of “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Which is why it’s worth rediscovering the man Grant actually was. We should remember how much he benefited the entire nation, including the Confederacy—black and white members. As Grant wrote in his memoirs:

“The great bulk of the legal voters of the South were men who owned no slaves; their homes were generally in the hills and poor country; their facilities for educating their children, even up to the point of reading and writing, were very limited; their interest in the contest was very meagre–what there was, if they had been capable of seeing it, was with the North; they too needed emancipation.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.