My alarm went off far too early, but I rose from bed and then ascended — in the dark, in a van on winding roads — Pico do Arieiro, one of Madeira’s highest peaks. I sat perched above a thick mass of clouds, and, at 7:01 a.m. sharp, the sun crept over the top. It’s a scene that repeats nearly every day on this volcanic island set in the Atlantic Ocean. But I was just as interested in what I could not see that morning: the Laurisilva forest veiled in mist.

This year, Madeira’s Laurisilva celebrates the 25th anniversary of its UNESCO World Heritage designation. Humid, evergreen Laurisilva once covered much of southern Europe, but the forest, named for its numerous Laurel species, is now limited to the Canary Islands, Azores and Madeira, which has the largest remaining old growth tracts.

Millions of years ago, birds and ocean currents carried seeds from the mainland to the Macaronesia islands. Forests grew from volcanic rock. Some 500 endemic species of birds, lizards, insects and gastropods evolved on Madeira alone, and when the last ice age wiped out continental Europe’s Laurisilva, the ocean’s warm embrace kept the islands’ climate stable enough to sustain the forest ecosystem.

When Portuguese sailors arrived — by chance, like scattered seeds — to Madeira in 1419, Laurisilva occupied most of the island. Early settlers harvested wood for building houses, churches and boats; they foraged foods and traditional medicines from its depths. “The forest was used for everything you can imagine, especially the larger trees,” says Paolo Oliveira, a conservationist and board member of the island’s Institute of Forests and Nature Conservation.

Now, just 20% of Madeira is covered with Laurisilva, mostly on the less populous northern side of the island. In the forest’s place, homes rise with their red-tiled roofs. Banana trees and vineyards cling to mountainside terraces.

On my first days in Madeira, my gaze turned to the ocean, where rock faces meet crystalline waters and brightly painted wooden boats anchor in harbors. Oceans, afterall, define islands. But it took a walk in the cool, damp forest to illuminate life and culture on the island. You can eat and drink the Laurisilva’s influence, bathe in it, hike through it, plant your feet in it and stand in awe.

Sunrise at Pico do Arieiro

Pico do Arieiro is just over a half hour from the capital city of Funchal, and all I could see from our van’s windows were dozens of headlights snaking behind us. If you rent a car on the island, you can drive to see the sunrise on your own, parking in one of two lots at the peak. Bring a blanket and sit with fellow early risers. I joined a small group from the Savoy Palace Hotel, and our driver delivered us to a table on the road’s thin, grassy shoulder. It was set for our arrival with coffee, pastries, charcuterie and cheeses, and we waited for the sunrise wrapped in cozy fleece throws.

Madeira’s mountain corrals clouds as they pass over the island. From our vantage point, all we could see were the tip-top of peaks covered with scrubby evergreens skittering in the wind. The moon still sat in the sky. Finally, when the sun yawned above the sea of clouds, it cast an intense burst of light onto the white backdrop.

Here’s the miracle. As those clouds hovered over the island, their moisture condensed on the leaves of the Laurisilva below. From the tips of Til Laurisilva, Barbusano Laurisilva, Vinhático Laurisilva and other flora, water droplets fell to the earth and began to filter through soil and rock. “The Laurisilva forest has a very important role in capturing water,” explained Nuno Goncalves, director of the agricultural division of Madeira’s water department. Every day, the forest harvests water from the air and sends it deep into wells and cascading down mountain streams.

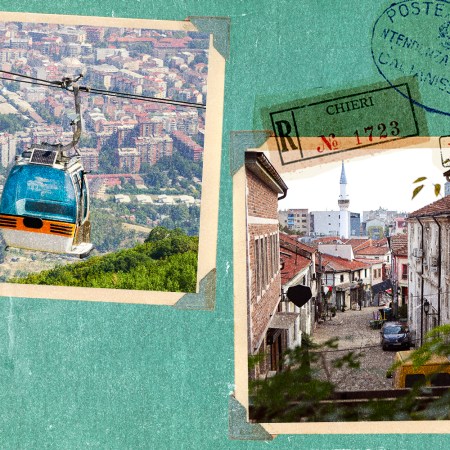

Disappear Into Madeira, A Wild Island Retreat off the Coast of Portugal

A hidden secret off the coast of Europe, Madeira is your next dream vacation destination.

Into the Fog at Fanal

The engine of my rented Nissan Micra wheezed with effort on the steep roads to Fanal, and once I reached a high plateau, I could hardly see 20 feet in front of me for the clouds. Long-horned cows grazed on the side of the road and sauntered, unbothered, between lanes. Hikers hardier than me appeared suddenly at veiled trail heads.

Fanal sits within the UNESCO World Heritage Laurisilva forest and between the island’s Seixal and Ribeira da Janela mountains. The area’s Til Laurisilva hunch at the waist like old men. The trees predate human contact to the island and are estimated to be between 400 and 800 years old. Most hours of most days, Fanal is shrouded in cloud cover, recalling a forest of fiction and fantasy, like something out of Robin Hood or Lord of the Rings. Its eerie, ancient backdrop is as much a draw for hikers as it is influencer bait, drawing women in flowing, full-length dresses and their hired photographers.

I squeezed into a parking space in a lot carved out for five or so cars (put “Fanal forestry station” into Google Maps to locate it) and wandered around the grass-covered landscape, admiring sturdy twisted trunks and watching as other visitors disappeared over a hill and into the mist.

“It’s very nice from the scenic point of view, but what you have in Fanal are old trees without regeneration. It’s a place that was heavily impacted by man, and nowadays it’s not recovering,” says Oliveira. “It’s dying Laurisilva.”

Still, go to Fanal, if nothing else but to close your eyes and imagine being an ancient tree on an even older plateau. Besides the wind and my footsteps, all I could hear was the dripping of water from leaves onto the clay. I touched my hair and it had soaked through; droplets formed at the tip of my frizzy bob.

Take a Levada Walk or Two

I followed closely behind mountain guide Tiago Afonso on Levada do Alecrim, a blissfully flat, seven-kilometer hike.

Madeira’s levada network dates back to the 15th century when workers known as Rocheiros first chiseled and dug irrigation channels to transport water from the northern part of the island to farms and settlements in the south. That vast system, around 3,000 kilometers in length, still satisfies all of the island’s water needs. Narrow walking paths hug many of the channels, and the Laurisilva grows around it, cocooning the man-made trails. Every now and again, Afonso would call out a warning to duck, lest I slam head first into a low-hanging branch.

Short of extreme canyoning, a levada walk, says Oliveira, is the best way to experience the Laurisilva. “My kind request for visitors is to respect the forest,” he says. “She’s been there for many millions of years.”

On my hike, I saw rainbow trout, introduced to the island in the 1950s, dart down the slim waterways. Afonso pointed out endemic blueberry shrubs, not yet full with fruit, and tiny wild strawberries peeping red from embankments. There was wild oregano and an arugula cousin, plus rare purple and rarer white orchids that die when transported out of the forest. Vinhático Laurisilva, Afonso told me, was heavily harvested for its red wood, and if I looked closely in Funchal’s cathedral, I would find it in the altars. At the end of the trail, young things lounged on sun-drenched rocks at the base of a small waterfall. I stripped down to my bathing suit and glided into the chilly turquoise pool.

The Alecrim trail sits around 1,300 meters in elevation. At certain moments, the sun burned through the evergreens; at others I could feel a faint mist kissing my arms. Levada das 25 Fontes rambles just below at 964 to 1,288 meters high. As the elevation changes, says Oliveira, the character of the Laurisilva’s botany morphs, so if you have time during your visit, try hikes at varying heights.

The moderately challenging, 8.6-kilometer 25 Fontes is one of Madeira’s busiest, most picturesque trails (there’s also a mountain cafe midway through for a civilized espresso). To access the path, I walked with a guide through a pitch black tunnel. Water lapped at our sneakers, and iPhones lit the way. On the other side, cream-colored lichen grew thick on branches that at mid-morning still dripped water onto the ground. Bryophytes covered tree trunks like shaggy green blankets. At the viewing platform for the dramatic Risco waterfall, mist hung in the air. Water rushed from cliff faces and through channels and over mountain rocks; it’s the soundtrack and life force of the forest.

At Sea Level

The only way to reach Fajã dos Padres is by boat or a cable car that glides down from a cliff. The organic farm covers a sliver of land next to the sea, and you can stay overnight or visit for a traditional meal at its restaurant. After a nerve-wracking descent, I walked down a path lined with banana trees, each supporting a fat cluster of fruit. For lunch, I sat facing the Atlantic and ordered a local delicacy: black scabbard fish harvested from deep waters off the island and paired with sautéed banana. Driving west from Funchal to Fajã dos Padres, I had passed banana farms at every turn.

The levada system, fueled by the trees and clouds, irrigates those farms. It also directs water into the island’s world-famous vineyards, from which my favorite souvenir was born: a 1983 Barbeito Malvasia that I sipped a cordial glass at a time once I returned home. The levadas deliver water to sugarcane crops, and in the late 15th century, sugar — that white gold — made land-owning islanders rich. (Visit the Museum of Sacred Art in Funchal and see the Renaissance treasures that sugar purchased.) Sugarcane still grows on Madeira, but you’re more likely to consume it in liquid form, as an agricole-style rum in poncha, the island’s signature cocktail. The rum-citrus-honey concoction goes down easily, dangerously. Best to fortify yourself with espetada, a dish of beef often skewered on laurel sticks and seasoned with their leaves.

Goncalves’ department serves some 30,000 farmers on the island, most of whom work tiny plots of only 500 to 700 meters. Each receives a fixed amount of water, on a specific day, delivered in a flooding gush over their fields.

On the Northern side of the island, opposite of Fajã dos Padres, I parked in the town of Seixal. Madeira has few sandy beaches; many are man-made. But the naturally occurring beach at Seixal promised black volcanic sand and stunning views, so I walked on a steep path from the town center to the ocean (there’s sardine-can-tight parking closer to the beach for the brave). I weaved in-between stone houses with brilliant blue doors. I passed a gardener who had just lifted a partition between his vegetable plot and a levada. A half inch of water covered the soil.

At the beach, lithe surfers rode modest waves into shore. Tourists waited for a turn to pose in front of a waterfall that showered from the mountainside onto glistening rocks — water I imagined that was born of an early morning cloud hovering around Pico do Arieiro. After a quick sunning, I left the beach to go find lunch, and Seixal’s black sand clung stubbornly to my feet. There was no shower nearby, so I dunked my feet into a levada, washed them clean and trekked back uphill to my car.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.