For decades, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera ran the Sinaloa drug cartel — one of Mexico’s most powerful criminal mafias — and helped smuggle billions of dollars’ worth of drugs while employing brutal and murderous methods to consolidate his power. But last Wednesday, his reign officially ended when he was sentenced by a U.S. federal judge to spend the rest of his life in prison.

Guzmán was convicted on drug, murder conspiracy and money laundering charges following a three-month trial that started this past winter. Last Wednesday morning, the infamous cartel leader walked into the courtroom at the Federal District Court in Brooklyn wearing a grey suit and sporting a newly grown mustache. He blew a kiss to his wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro (who attended most of his trial and was implicated in some of his crimes), then shook hands with each of his attorneys before taking his seat.

It might be the last time the public ever sees El Chapo, the man known for bloodshed and corruption. But will his life sentence have any major impact on the international drug trade? With technology and the internet making drugs more accessible than ever and the distribution of deadly compounds like fentanyl on the rise, what effect does jailing the leaders of cartels actually have?

Taking Down the Kingpin

Guzmán’s guilty verdict in February thrilled U.S. authorities.

“There are those who say the war on drugs is not worth fighting,” said Richard P. Donoghue, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York according to InSight Crime. “Those people are wrong.”

Then-Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen said at the time that the verdict “sends an unmistakable message to transnational criminals: You cannot hide, you are not beyond our reach, and we will find you and bring you to face justice.”

Finding and arresting Guzmán was part of a strategy used in the U.S. starting in the early 1990s, wherein officials targeted cartel leaders with the idea that if you take out the head of the organization, the rest will collapse. But InSight Crime’s Steven Dudley writes, “The idea that this trade is dominated by vertically integrated organizations, each run by a single mastermind such as El Chapo, is a myth — and a dangerous one, in that it may undermine international efforts to slow drug trafficking and combat the violence of criminal groups such as the Sinaloa Cartel.”

Meanwhile, an article in The Guardian claims arresting El Chapo did not “magically rid Mexico, or the U.S. of violence or drugs” and that in fact, the kingpin strategy “has enabled new forms of crime to flourish.”

According to journalist Jessica Loudis, the start of Mexico’s drug war in 2006 meant that as Mexican and American authorities took out cartel leaders, “groups fractured and new ones emerged.”

Mike Power, investigative journalist and author of Drugs Unlimited: The Web Revolution That’s Changing How the World Gets High, explained to InsideHook that there will always be other “capos” (or heads of criminal organizations) fighting for “dominance and control of what is, after all, a multi-billion-dollar business. Cartels are no different to any multinational corporation (except for the killings and torture).”

As cartels fragmented, they had to change their business structure and in order to distinguish themselves in a now-crowded field, the “new groups pioneered the use of sadistic, headline-grabbing violence,” writes Loudis. There are now more low-level king-pins to go after, and once caught, narcotraffickers are usually quick to cut plea deals and help prosecutors catch former bosses and colleagues for a shorter sentence themselves. At least 14 of the witnesses the government called during El Chapo’s case used to work for him.

Power added that jailing El Chapo will likely have no impact on the global drug trade, though. As long as there are people who want to do drugs, someone will make it their business to provide those drugs.

“We comfort ourselves with the delusion that supply-side measures can ever reduce demand. Drugs are the only commodity sector within capitalism where we ignore, or pretend to ignore, the iron laws of supply and demand,” he said during an email interview. “People want drugs. Drugs are illegal. Drugs will therefore continue to be sold at vast profit — and huge social damage under prohibition.”

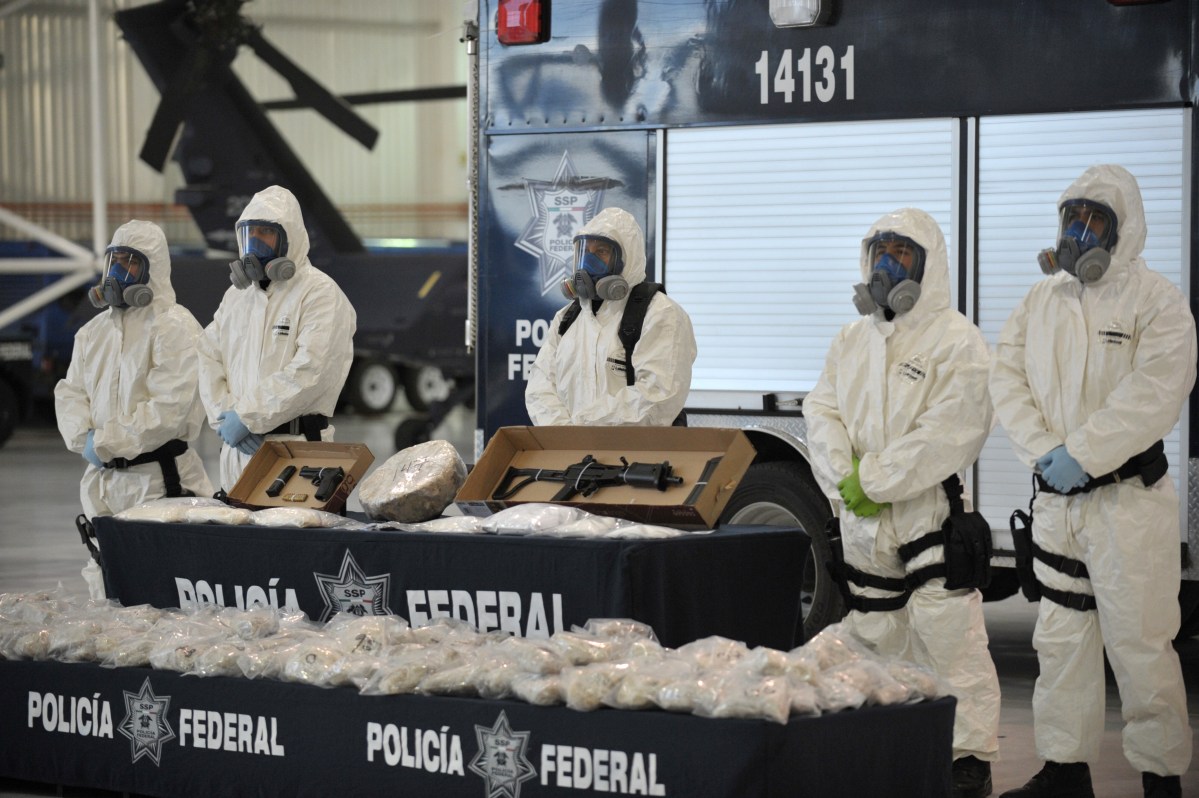

And Ozy reports that since Guzmán was expedited to the United States in January 2017, business for the Sinaloa cartel has boomed. The article detailed how Mexican authorities found 50 tons of methamphetamine, worth $5 billion, in a hidden Sinaloa lab in August 2017.

“The Sinaloa cartel is still basically operating with the same power and reach,” said Mike Vigil, former chief of international operations for the US Drug Enforcement Administration, to CNN after Guzmán was convicted in February. “They continue to be the most powerful drug organization in the world.”

The Future of the Drug Trade

Technology and the internet have also changed the drug trade. Namely: the distribution of fentanyl. Since it is so potent (it can be 50 times stronger than heroin), fentanyl can be moved in smaller quantities and can be sent directly to the U.S. by mail. It is then sold by small traders using the dark web, encrypted messaging services or social media. It was even sold on Craigslist in Los Angeles.

“The internet — or dark web markets — has changed drug use, culture, sales and marketing and distribution fundamentally,” explained Power. “One market was just shut down that had over 1,000,000 users. Now, that is a vanishingly small in the wider global context. But there is no doubt that we are witnessing a fundamental shift, one which I expect to continue growing. The net has increased access to more drugs to more people than ever before. In the past, to become a drug dealer you needed to know criminals. Now you just need a postbox.”

People want drugs. Drugs are illegal. Drugs will therefore continue to be sold at vast profit — and huge social damage under prohibition.

The Sinaloa Cartel seems to have recognized fentanyl’s influence, and has started supplying the drug. The powerful synthetic opioid is made in China and often trafficked through Mexico, and many of the biggest fentanyl seizures in the U.S. in 2018 were linked with the cartel. That includes 33 pounds in Boston, 144 pounds in New York and 118 pounds in Nebraska. Fatal overdoses in the United States involving fentanyl continue to rise as the drug replaces heroin. In 2018, there were 31,897 deaths involving fentanyl or a similar drug, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Power said cartels will always thrive because criminals will supply “whatever the market needs and whatever is profitable.”

“What is the answer to all of this: simply, we have to seize control of these markets from criminals, from gangsters and murderers, and hand it to the chemists, the bureaucrats, the government,” he said. “You’ll never stop anyone getting high. But you cut out an awful lot of bloodshed if you make it your goal.”

Providing a deterrent

Before Judge Brian Cogan issued the sentence, he gave Guzmán a chance to speak. Guzmán used what is likely his last public hearing to accuse the judge of not giving him a fair trial.

“My case was stained and you denied me a fair trial when the whole world was watching,” Guzmán said, reading from a prepared statement and speaking through an interpreter. “When I was extradited to the United States, I expected to have a fair trial, but what happened was exactly the opposite.”

This statement is in response to a Vice News report that claimed a member of the anonymous jury contacted a reporter and said that at least six jurors regularly looked at social media coverage of the trial and learned about evidence not introduced during the proceedings. They then lied to the judge about these actions.

“Since the government of the United States is going to send me to a prison where my name will never be heard again, I take advantage of this opportunity to say there was no justice here,” Guzmán said.

Guzmán also lamented about the poor conditions he has faced in prison, claiming he has had to drink unsanitary water and plug his ears with toilet paper at night to sleep. He is not allowed to see his wife and he cannot hug his twin girls when they visit. He called the solitary confinement he has been in “psychological, emotional and mental torture 24 hours a day.”

During the sentencing, Judge Cogan announced he had no choice but to sentence Guzmán to life (he also received an additional 30 years and was ordered to pay $12.6 billion in forfeiture). But the judge also noted that the “overwhelming evil” of the drug lord’s crimes were clear.

Though it is hasn’t been confirmed where the drug lord will spend the rest of his days, he will likely be sent to the United States Penitentiary Administrative Maximum Facility, or ADX, in Florence, Colorado, a prison “not designed for humanity,” according to The New York Times. El Chapo has twice escaped prison. He will likely spend 23 hours a day inside a solitary cell that has one narrow window placed high on the wall and angled upward.

Will his fate deter others from joining or participating in a cartel? Alejandro Hope, a security analyst, doesn’t think so. He explained to InsideHook that deterrent would’ve happened when Guzmán was extradited from Mexico; once convicted, people knew he would be sentenced to a very long prison term. But we’re not currently seeing any fallout in terms of cartel activity.

“Is there is a decline in the drug trade over the past three years? I don’t think so,” Hope told InsideHook during a phone interview. “Has there been a decline in prohibition related violence? I don’t think so. Are there fewer people connected to organized crime than two-and-a-half years ago? I don’t think so.”

Hope also explained that those who would be the most affected by Guzmán’s arrest would be the immediate family, but “as far as we know, part of the criminal structure built by El Chapo is now run by two or three of his sons.”

So why capture the kingpins?

Hope explained there are two reasons to go after the leaders of cartels: one ethical, one strategic.

“Ethically, because these people are horrible human beings that are responsible for the death, torture and maiming of literally thousands of people,” Hope said.

And strategically, if law enforcement doesn’t go after the kingpins, then drug dealers would get the idea that once you reach a certain level of prominence, you’re untouchable.

“And how do you reach that level of prominence? Basically by means of violence. So I think there is a case to be made that we need to send the message that if you get too big, you’re going to go down,” said Hope.

Jaime Lopez, another security analyst in Mexico, said that while the capture and imprisonment of El Chapo will not stop the drug trade or provide a long-lasting solution, it is still something for law enforcement to be proud of.

“It took a lot of effort, it took a lot of time, it took a lot of lives. From a Mexican perspective, it was the right thing to do, and it was really hard, it’s a victory,” he said during a phone interview.

He continued: “The notion that we take down kingpins because that will stop drugs flowing through the streets, no. We stop kingpins because they’re criminals, because they’re murderers, because they’re quintessentially bad people, and because as a society we cannot let these people operate. That’s why we take down kingpins. The rest? The rest is much more complicated.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.