It wasn’t my first concert, but it was my first experience with club-loud electric rock ’n’ roll.

See, I had been born, but I was not aware; I had warmed myself by the fires of Galilee and the high-hissing warmth of a Korvettes’ bought stereo spinning starry, soul-changing music, but the warm waters of the River Jordan had not yet washed me.

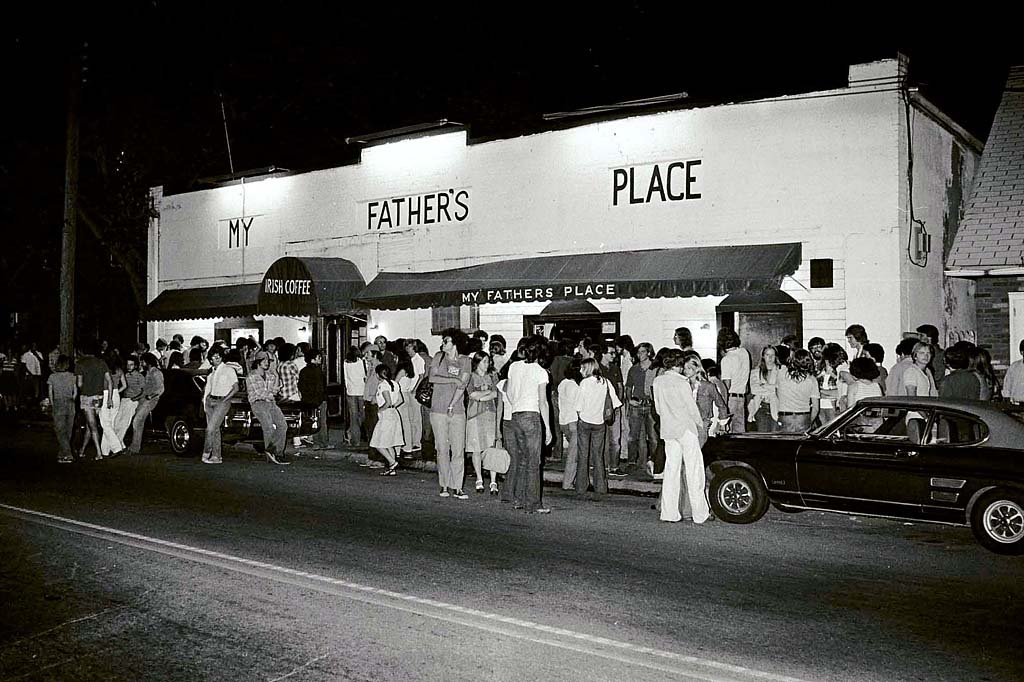

My River Jordan was My Father’s Place in Roslyn, Long Island. My Baptist, my John, my Yochanan, was the Good Rats.

It was the age of Mary Tyler Moore, Melba Tolliver, M*A*S*H and Bill Mazer, it was the age of memorizing reruns of The Odd Couple and feeling impossibly adult because you read Esquire, it was the age of twisting phone cords around your fingers as you wore holes in your bedroom carpet talking to friends about impossible foxes in peasant blouses; my god, all these things that are “as obsolete as warships on the Baltic.”

It was the age of custard-yellow high school hallways dissolving into Escher Stairs of terror and boredom. Remember that feeling in the top of your chest when you wanted to be anyone but who you were, and anywhere but here? Every moment you were inside that sibilant redbrick and glass cavern full of clique and boast and inadequacy you could think of nothing but rushing home to hear that record. True, friend? Every weekday you would you tear the 648 strides from the bus stop, slam the screen door on your parents stucco Tudor redoubt, say something odd to the cat, and climb the stairs with a handful of Lays crunching in your fist. You would unsheathe a record, flick a switch, narrow your eyes, and study that f*cker as you had never studied algebra or even your Haftorah.

Often, you weren’t alone: remember that age when baseball talk gave way to Beatles talk and Saturn V dreams surrendered to mad speculation about “Idiot Wind”? You would share your wild voyage of discovery, you pimply virgin Shackleton you, with your closest friends: Have you heard this, Tim this is Pleasures of the Harbor, said Matt Goodman; and Eric Sheidlower presented you with Black and White by The Stranglers as if it was the commutation of a Prison Sentence (which, of course, it more or less was, the sentence being the suppurating pastel and Monsanto hole that was the suburban 1970s); and Andrew Cutrofello taught you to think of The White Album as a sacred text, pulling out his guitar to illustrate important passages. Puffing cheeks that did not yet need shaving, these magic suburban children would flash a half smile that wordlessly said, welcome to rock ’n’ roll, welcome to the secret that separates the children from the teenagers.

Yes, you were there, that is why we are friends. That is why you are still reading.

I had fallen for music, and fallen hard, a few years earlier. It had become a wild, careening obsession, the sports I had never played, the hobby I had never had, the girlfriend who I certainly didn’t have. Records were brilliant, because they were full of myths and legends, the worthy successor of the books we had read about astronauts or dinosaurs; and records were like an onion, layers could be peeled to reveal new magic as you understood more about the process, the artists, the B-sides, the bootlegs, as you found another quirk, tic, or lyric that told you something about you.

But the lord had only teased me, I had not been made his wife; I was 16 (unless I was 15, because memory is entirely secondary to experience), and I had not yet experienced the frantic, feral, whistling, squealing, ball-kicking and sternum punching experience of live, small-venue rock ’n’ roll.

We were here tonight, in a street in Roslyn that was neither wide nor narrow, to see The Good Rats. If you lived in the New York area in the 1970s, you very likely remember them. True, every suburb and every college town, screaming with Mateus and Michelob-waving children, produced beloved local bands; but the Good Rats, who delivered thick-riffed, cleanly played high-end pop metal that landed somewhere between Santana and Mountain and Deep Purple, really were an amazing band. The fact that they never achieved national prominence obscures that fact that one of their albums, 1978’s From Rats to Riches, is a fantastic record that still sounds great today (it almost sounds like proto-Stoner Metal, but with an extraordinary and powerful vocalist).

A car full of WLIR had taken us there. I remember no details of the car, apart from the fact that “Jessica” was on the radio (I’ll be honest, I don’t even remember what time of year it was). We had an older siblings license in our wallet, presented, when requested, with a shaking wrist and a silent prayer. Bizarrely, it worked (our children may find it deeply strange to learn that the New York State license, in the age of Jimmy Carter, did not have a picture on it), and we instantly felt older, instantly felt like we may have actually earned the right to wear the brown corduroy jacket that we had taken from that same older brother’s closet. Never again, not ever, would we ever feel like a child, because we had passed through the portals of a rock ’n’ roll club, a brilliant low ceilinged room smelling of smoldering Marlboros and salty beer and patchouli and Jean Nate.

We contracted our shoulders and slid through the venue, which was full of people who were impossibly older –23 or even 26! We found a spot on the bleachers, to the left of the stage.

I had seen concerts of a quieter nature, and these had their own wonder, the delight of wise and funny men and women sharing their songs; and I had even seen rock shows in great old vaudeville houses whose walls, full of rococo babies and sirens, were opaque with soot. But I had no idea what it was like to have amps in your face in an acoustically finite smoky shoebox, and I certainly did not know that it would be so different, so life changing.

Remember when the full force of the holy electric first hit you in the chest? Remember when you discovered the wallop of the blue and wet god that was live rock ’n’ roll?

The Good Rats opened with a song that began with a rhythmic blast of a single chord, repeated; it was like the Titanic sending Morse code from hell. Then the drums rumbled in like the march of a barbarian army, rising against the forces of adult expectations.

That first shock of club-loud live electric music was like being hit by the stone that rolled away from the tomb in Golgotha, that’s really what it felt like. It was both clean and clear and pure, like pink and orange hallelujah clouds parting in a low sunset sky to reveal the beaming ray-face of a new god; and it was dirty and decadent, like the ash and beer spill that was underneath my feet, like a rock ’n’roll cartoon of greasers and dog collars and horny Crumb characters. And no one, nothing, had prepared me for the elation-shock of volume: The dissonance and harmony of a well-tuned electric guitar pinched into a barre chord sounded like a thunderclap, and the sound twisted from my thighs to my spine, and my mind was almost dumbed by awe.

I did not know it could be like this. I mean, of course I knew the almost erotic pleasure and terror of loud music (as my devotion, almost unhinged, to the Kinks and the Pistols and the Ramones and the Damned evidenced), and I knew the deeply personal grace of a song reaching two fingers into your soul to pet the underside of your heart and pinch out a tear. But until that moment the Good Rats hit the stage and played “Taking it to Detroit,” I had only known music in the flatlands. I did not know it could be behind you and underneath you and within you and it could be hell raised to the sky and heaven dropped to it’s knees. In the first seconds of the Good Rats’ set, it was like god dictating to Brian Wilson, or Oppenheimer seeing the face of Big Joe Turner in the fireball of Trinity.

And I know that what I felt and saw and heard was real, not just the projection of excitement and novelty. The Good Rats were a fierce, ripping, almost frightening live act (they had the peculiar quality of always playing like they were holding a grudge), and I know it wasn’t sex (you know, in that omigod Bowie omigod Frank-n-Furter way), because the Good Rats, who looked like Coptic Christians plumbers, were one of the least sexy bands in history. What I experienced that night forty years ago was the power of the animal sound, which resembled a full-body form of that feeling you get when you’re five and you cut into a piece of construction paper with those little kidschool scissors, only the kid is licking an electric socket.

Before that moment in Roslyn, rock ’n’ roll, no matter how much I loved it, no matter how much I called it me, had been a logogram, not the object itself. But after Roslyn, I could take that shock and joy of the live experience with me into the stereo-lands and make any 2-D experience 3-D. I now knew that this power existed, and I could apply it to everything I listened to.

As we age, music becomes a less social, more intensely personal experience, an encounter that takes place in the car or between two hermetic headphones. Yet we are still informed by that moment when we were initially filled with the hot fire ants of live, intimate rock ’n’ roll. And, although everything we touched, everything we watched, even the silence of escape and the map-less life we lead in the age before the ether was conquered, is “obsolete like warships in the Baltic,” we are still hearing the bell that was rung at that moment; it is still sending harmonic waves around our soul.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.