In 2007, the New Yorker’s Alec Wilkinson profiled the East Village fixture Jimmy Webb — the longtime salesman, manager and buyer of the punk clothing store Trash & Vaudeville — who had come to New York City as a teen runaway in the 1970s, shot heroin and lived in Tompkins Square Park, sold Iggy Pop all his tightest pants and wore his even tighter. Contextualizing this downtown punk icon at the cusp of the Gossip Girl era, Wilkinson collected testimonials from a number of the teens of St. Mark’s Place, including one “Owen Kline, who is fifteen. Kline is tall and handsome, with big feet, a round face, and dark eyes. He lives with his parents uptown and hopes to be a director.” Out of respect for the privacy of a minor, Wilkinson did not mention who Kline’s parents are — they are Kevin Kline and Phoebe Cates — or that he was already an actor, having appeared in The Squid and the Whale a couple years prior. Kline told Wilkinson about the then-fortysomething Webb:

“I’ve heard the entire Jimmy story a couple of times,” he told me one day in the store. “I know everything about him—he’s very open about his personal life. What would you like to know?”

I asked if he knew where Webb had grown up.

Kline shrugged. “Who knows where—Virginia or Vermont, or something like that,” he said. “He was living in a suburb, he went to high school, then community college, then ran away from home—interesting move. Years ago, there were so many more things to rebel against. It’s like Marlon Brando in ‘The Wild One,’ where they ask him, ‘What do you rebel against?’ and he says, ‘What have you got?’ You’ve seen that?”

I said I hadn’t.

“Well, rebellion’s turned more into a style and a fad,” he said patiently. “It’s pseudo. It’s also got real poserish. Jimmy’s authentic, though. He’s so alive, very funny, very eccentric. Anyway, so he met, I don’t know, along the way some maybe famous guy who was also running away, and came to New York City, I think in the seventies, worked in bars and got really into parties and drugs, went dancing at Studio 54, and then he got older, cleaned up, and became Jimmy from Trash and Vaudeville.”

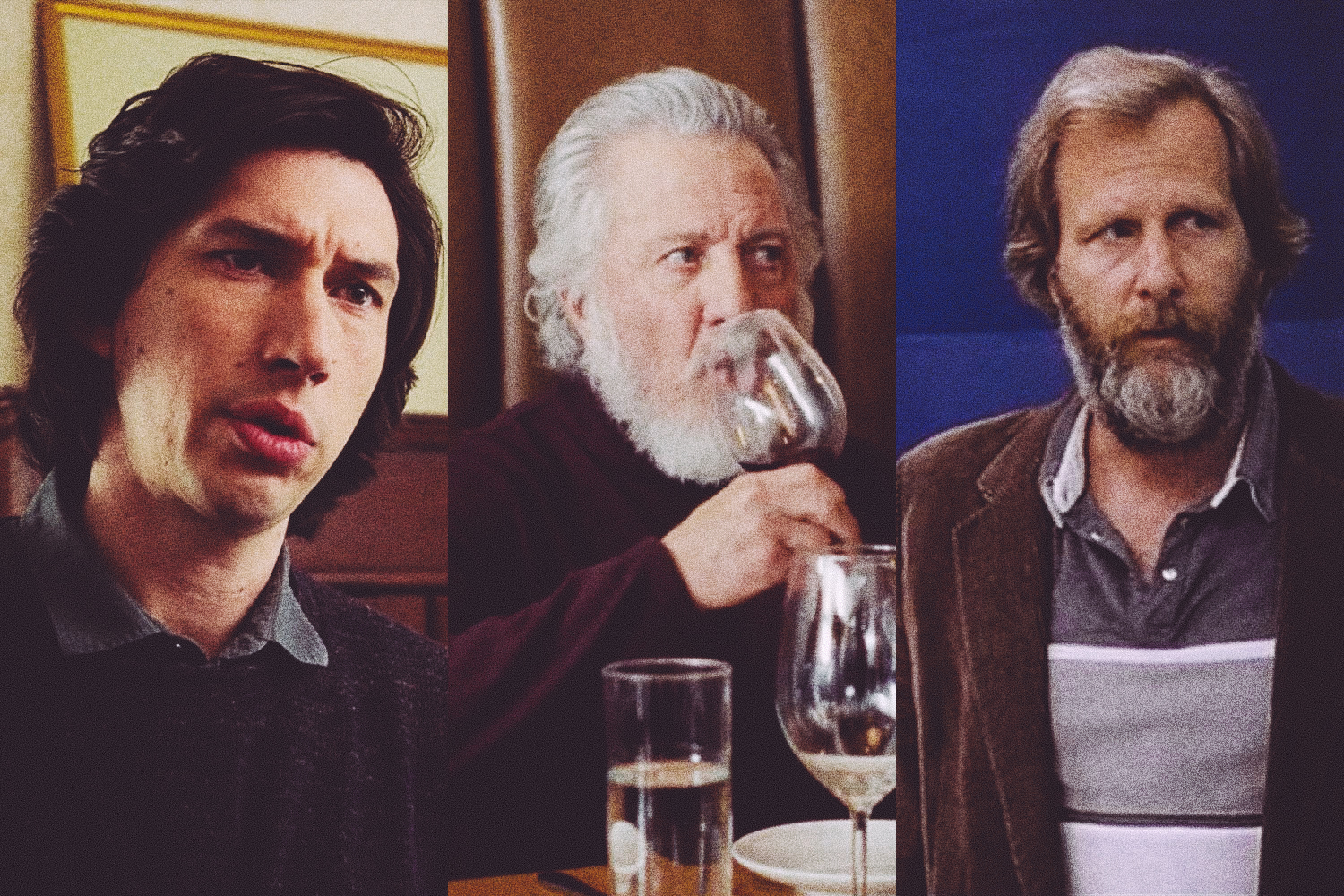

Fifteen years later (and two years after the death, from cancer, of the beloved Jimmy Webb), Kline has, indeed, become a director, and his feature debut, Funny Pages, which comes out today, is very much the work of a filmmaker who was once a teenaged admirer of a crusty, middle-aged avatar of another era’s bohemia.

Funny Pages, too, concerns a young man who runs away from home and rebels for rebellion’s sake: A high school senior from a high-property-tax suburb who decides, over winter break, to drop out, move out of his parents’ house, and make his way as an underground cartoonist. The film is grody, farcical and sharp about the youthful arrogance of artistic pretensions, and it’s animated by the paradox of precocity — namely, that distinguishing yourself from your peers by your interest in another time’s obscure culture means throwing yourself in with adults who, you are maybe too young to quite realize, are tragicomic maladjusted marginal loners with poor hygiene. Ghost World is the obvious antecedent to Funny Pages; the films share not only a deep connection to the graphic novel form, but an interest in the knotty dynamics of niche subcultures and the age-gap friendships they foster.

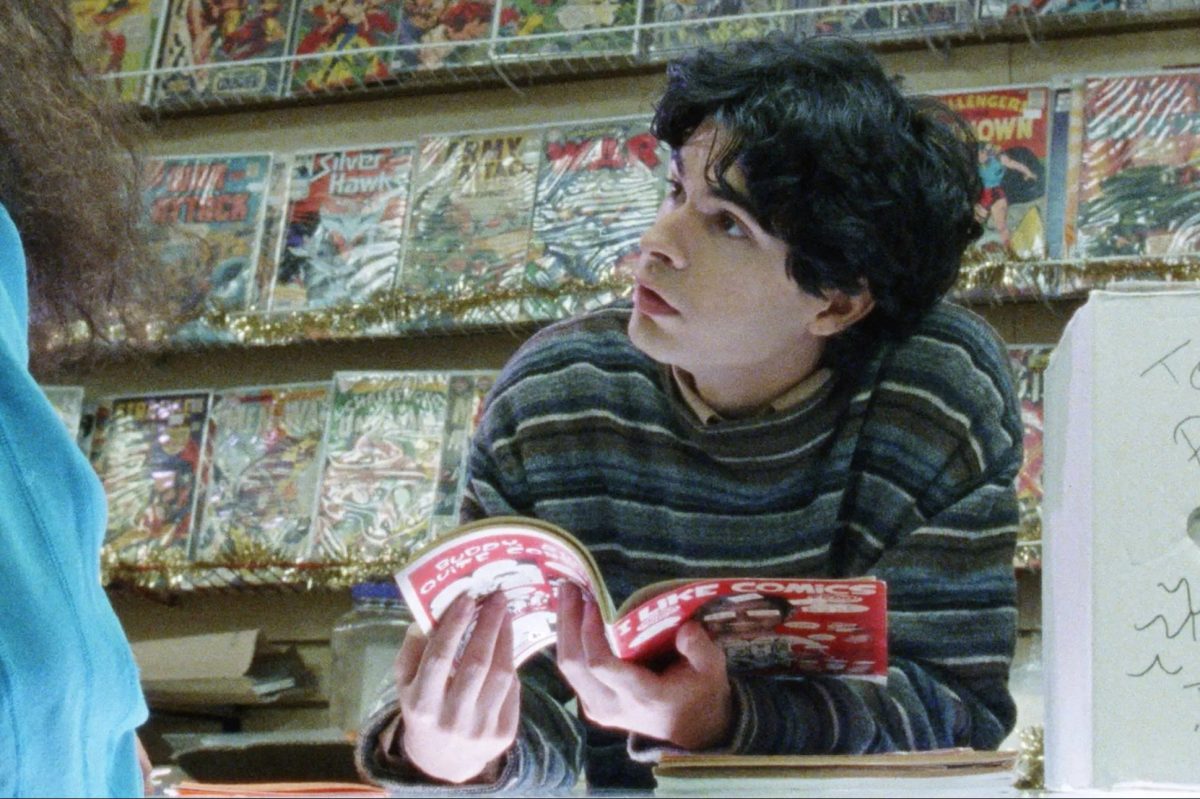

Funny Pages opens in the art room, after school hours, where Robert (Daniel Zolghadri) is having his portfolio reviewed by middle-aged art teacher Mr. Katano (the playwright Stephen Adly Guirgis), who advises him to “always subvert.” The two share an appreciation for the technical ingenuity, historical interest and transgressive sensibility of Tijuana Bibles, confessional comics, raunchy underground cartoons and other ephemera — stuff for collectors, though perhaps a borderline inappropriate subject for a teacher-student mentorship session.

Robert is handsome, unlike everyone else in the film, a dark-haired and intelligent-looking boy growing into himself after an introverted adolescence hinted at by the faint acne scars on his cheeks — in contrast to his best friend, close talker Miles (Miles Emanuel), whose zit continuity over the film’s weeks-long time frame is one of its signal technical achievements. All the supporting players in the film are marked by the kind of quirks of appearance that an R. Crumb would lovingly explode into thick-lined grotesquerie: yellow teeth, missing teeth, greasy hair, dry hair, sparse hair, hairy shoulders, uncombed eyebrows, jowls, wrinkles, an umbilical hernia, a sweat sheen, a dripping nose.

The characters look even more mottle-skinned in extreme close-ups on grainy Super 16mm film, shot by cinematographers Hunter Zimny and Sean Price Williams — the latter a regular collaborator of the Safdie Brothers, with whom Kline has worked since his teens and whose Elara Pictures produced Funny Pages. Like them, Kline prefers an intuitive casting process and often seeks out unconventional performers; Funny Pages captures the at times almost overwhelming tactility of the kind of Tri-State Area Wild Ones that a teenage Owen Kline, wide-eyes on St. Mark’s Place, once described as “authentic… alive, very funny, very eccentric.”

There is a risk, in this kind of filmmaking, of coming off like a slumming rich-kid dirtbag. Fascination with “authentic, funny, eccentric” people who bear the visible evidence of an original, probably difficult life — this is an immature gaze that teeters precariously between open-hearted curiosity about the world and guffawing exploitation. That’s the line Funny Pages straddles, as skillfully as the Safdies straddled it in Heaven Knows What and Good Time, and it’s also the line Robert is learning to straddle in his own life.

After Robert tells his parents, through a mouthful of diner food, that he’s not going to college, he moves out of a neighborhood he apologetically calls “the middle-class part” of Princeton, into an illegal basement in Trenton, where the shower runs rusty and a stained boiler is always running, soaking everyone through their undershirts and making the atmosphere so thick that the greenish glow of the fluorescent tubes seems almost stuck in midair.

Robert earns a job working as an assistant for a public defender (Marcia DeBonis) after drawing an affectionate caricature of her; with her frizzy hair and snorting laugh, she’s a little less well-presented than Robert’s prim, wealthy parents, but more put-together than her impoverished clients. One client in particular interests Robert: hairlipped Wallace (Matthew Maher), first seen giving himself a sponge bath at the courthouse building’s bathroom sink. Wallace’s difficulty controlling his anger has led him to incite an ugly altercation at a local “Right Aid” (a glimpse of the pharmacy’s exterior confirms the knock-off spelling), but when Robert finds out that Wallace was once a color separator at Image Comics, he attempts to ingratiate himself with a man he now considers an Artist. Inspired by what is, it must be said, an incredibly marginal connection to the world he aspires to join, Robert butters up the standoffish Wallace with assurances of his (heretofore unmentioned) interest in classic superhero comics — evidence of Robert’s confused, mingled admiration for what he perceives on the one hand as refined industry craftsmanship and on the other as thwarted, tragic genius.

Robert is naïve enough to take as a given the maturity of the adults around him; he’s hurt by Wallace’s rebuffs and criticisms and fails to recognize the extent of his behavioral issues. Dressed in a teenage uniform of Goodwill sweater, scuffed sneakers and too-short pants — fine, even cool, on a artsy kid — his head filmed with dreams of rebellion and a weird wild life, he’s too young to realize how vulnerable and volatile all these people are, too inexperienced to understand that they barely know how to live. Warned that the random old cardboard boxes stacked up in the basement hallway constitute a fire hazard, Robert simply says he’s cool with it, like this is some anarchist squat. Spending all his spare time at a comic shop, he’s used to hearing people discerningly describe Scrooge McDuck cartoons as “sophisticated” because of some particular elegant line work, despite the fact that this stuff was, as Wallace says, made for “10-year-olds in the ’50s.” As both an appreciator and an artist, it is hard to be obsessive in a moderate, self-aware way. (I say this as an expert — namely, as someone who has approximately 10,000 hours of Turner Classic Movies saved on my partners’ parents’ DVR for the next time I visit. But I’m normal about it. And I assume that many of the authors of X-rated comics about anthropomorphized cats are likewise normal about that whole deal.)

In the basement in Trenton, Robert and Miles attempt to recognize kindred spirits in Robert’s landlord (landlord? roommate?) Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), a gentlemanly shut-in in off-white tube socks, who shares the space with a mysterious, equally middle-aged boarder named Steve (Cleveland Thomas Jr.). They do not quite seem to grok that Barry and Steve’s fondness for watching old movies on DVD, for listing off the credits of early TV stars and the names of midcentury cartoons, is a cultural-hoarder mentality, not connoisseurship, or that their interest in vintage pornographic comic books is not strictly the interest of an antiquarian.

Funny Pages comes out shortly after first Lizzo and now Beyonce have discovered that “spazz” is a slur — news to them, and maybe (maybe!) to an offscreen voice heard in Funny Pages, that of d.j. David “Dave the Spazz” Abramson, a long-time on-air personality at the famed free-form radio station WFMU. WFMU, which Robert listens to in his barely taped-together car, is one of the New York region’s last glorious bastions of real eccentricity and dogged flame-keeping for many obscurantist causes, not least novelty records by the Nutty Squirrels and other aural equivalents of MAD Magazine. Stuff for today’s Old Souls, maybe, as well as yesterday’s permanent man-children. The “spazz” nickname, in Funny Pages, signals a confrontational and self-deprecating awareness of the affinities between crate-digging and memorabilia culture and developmental disabilities.

Because on the other hand, Robert’s tentative awareness of everyone’s eccentricities also enables an attitude of casual condescension (which matches his transparently self-loathing cruelty to Miles). He calls one of Barry’s velvet paintings “incredible,” mistaking genuine kitsch for the ironic variety, and treats the people around like subjects for an underground comic book. The artist, even more than the art, must be handled with care; Matthew Maher is extraordinary, with his vibrating intensity and abrupt, badly modulated and conveying the depths of Wallace’s anxiety without sacrificing the comic punch of his antisocial outbursts.

Robert’s precariously balanced friendship with Wallace finally collapses in a Christmas Day farce back home in Princeton, via a drawing lesson that uncorks Wallace’s personal and professional disappoints and the contradictions of Robert’s dueling beliefs in inspiration and career-path professionalism, before climaxing in a moment of gross-out horror and a humbling recrimination that is Funny Pages’s most straight-played nod to coming-of-age film convention. Robert and Wallace’s relationship finally reminded me of the Jonathan Lethem short story “Super Goat Man,” in which a minor comic-book superhero moves next door to the narrator. A child at the time, Lethem’s narrator expresses a comic-crazed kid’s mixture of curiosity, at the newly porous border between himself and a legendary world of art and experience, and disappointment, at the diminished reality of a cartoon hero battered by life. Funny Pages is an edgy, hilarious and rueful picture of the messy middle where a kid on the way up meets an adult on the way down.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.