Eating with the seasons is something I’ve been doing my best to embrace for the better part of a decade. Between the farmers market and biweekly produce boxes, I’ve learned to enjoy fruits and veggies at their peak. The summers are filled with nightshades and stone fruits, while winter brings root veggies, chicories and citrus.

But it never really occurred to me that seasonal food extended beyond produce until a recent dinner at New York’s Sushi Ouji. The host explained to me how one particular dish changes, depending on the fish that’s in season at the time. “In the colder months, you’ll find richer, fattier fish like buri (winter yellowtail) or ankimo (monkfish liver),” says Ben Chen, chef at Sushi Ouji. “In spring and summer, we focus on lighter, cleaner flavors such as sayori (halfbeak), hamo (pike conger), tachiuo (beltfish) or different types of shellfish that are at their peak in warmer waters.”

Sometimes fishing seasons have more to do with the weather conditions than the water temperature. For Peter Tempelhoff, owner, founder and chef at Fyn in Cape Town, South Africa, his incoming fresh catch depends on the unique conditions of his location. “Game fish arrive in summer when the seas are calmer and it’s easier to catch them,” he says. “In winter, we tend to use more reef fish that are found closer to shore. We’re working with some of the roughest and windiest waters in the world, so keeping fish on the menu all year is a real challenge, but it keeps us flexible and in tune with the environment.”

And it isn’t just different types of fish that change from season to season. One type of fish can actually shift in flavor as the year progresses. “Conger eel is served as sashimi in spring when it’s still young and translucent, and in winter we serve the larger, fattier eel when it’s at its richest,” says Hirohisa Hayashi, chef and owner of Hirohisa and Sushi Ikumi. “Yellowtail is another example. Its name changes as it matures, and each stage is enjoyed in different seasons. In early summer it is called inada, then warasa as it grows and finally buri in winter when it reaches full size and flavor.”

Warming Temperatures Means Shifting Seasons

I live in the Northeast, and my backyard garden is still producing peppers. And up until a week ago, it was still yielding tomatoes and eggplant. Climate change is shifting the seasons, and as ocean temperatures rise, it’s shifting seasons for fish, too.

“This year, the Pacific saury — typically a symbol of autumn in Japan, usually in season starting in late September and October — became available in August,” says Mitsunobu Nagae, chef and co-owner of l’abeille and l’abeille à côté. “It’s said this is due to rising ocean temperatures, which resulted in an increase in plankton, leading to a boom in the Pacific saury population.”

Changing temperatures are also shifting where people source their fish. “I would say it’s been most noticeable for lobsters,” says Joe Anthony, managing partner and executive chef at Arvine. “They’ve shifted far more north to head for colder waters, and I would argue it’s become better to get lobsters from Canada compared to the iconic Maine lobster at this point.”

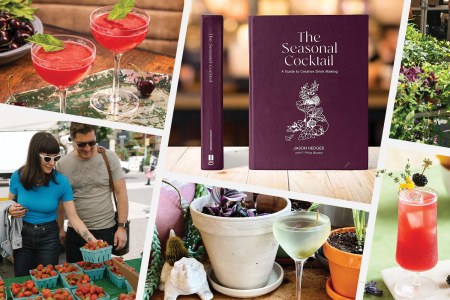

This Cocktail Book Wants You to Drink With the Seasons

“The Seasonal Cocktail” makes a case for farmers market produce in shrubs, syrups and infusionsSeasonal Produce Is a Boon for Fish

Fish has been a huge part of the Japanese diet for centuries, so it’s no surprise that many classic preparations include seasonal produce as part of the dish. As with many cooking traditions, they are passed down through the generations.

“One well-known example of a classic winter dish is buri daikon, a simmered preparation of fatty yellowtail and daikon radish, both of which are in season during the winter months,” Hayashi says. “The daikon helps remove any strong aroma from the yellowtail while absorbing the rich flavor of the fish. The result is a beautifully balanced dish where both ingredients enhance each other.”

As fish becomes fattier in the winter, rich, stick-to-your-ribs ingredients are a natural match. “On the other hand, when the fish has a more muted flavor, we pair it with lighter ingredients that help bring out its delicate character,” Nagae says.

Peak Flavor and Sustainability Go Hand in Hand

If you’ve ever bitten into a tomato in winter, you can attest to how nasty it can be — mealy and flavorless. It is totally worth the wait for a late summer tomato, and in the meantime, you can always make sauce with the canned version that’s been preserved at its peak.

“Seasonality reminds us to respect nature,” Chen says. “Eating what is at its peak not only means better taste but also supports more sustainable fishing practices. It’s about celebrating the moment and sharing that freshness with our guests.”

And Tempelhoff reminds us that even if you can get something, it doesn’t necessarily mean you should. “Just because there’s an abundance of a certain fish at a particular time doesn’t always mean it’s the right moment to catch it,” he says. “In many cases, that’s actually when fish are breeding or spawning, and harvesting them then can disrupt their life cycles and future populations. Choosing seasonal fish should involve understanding more than just supply — it should be about sustainability, too.”

Every Thursday, our resident experts see to it that you’re up to date on the latest from the world of drinks. Trend reports, bottle reviews, cocktail recipes and more. Sign up for THE SPILL now.