From Opera Man, Cajun Man and Canteen Boy to the title roles of Billy Madison, Happy Gilmore and The Water Boy, Adam Sandler has always played some version of the comedic man-child maybe a little too well for some people. Some were sillier and more juvenile than others, but the result was always the same. Throughout the ‘90s and into the early ’00s, he went for the most streamlined laughs possible and succeeded.

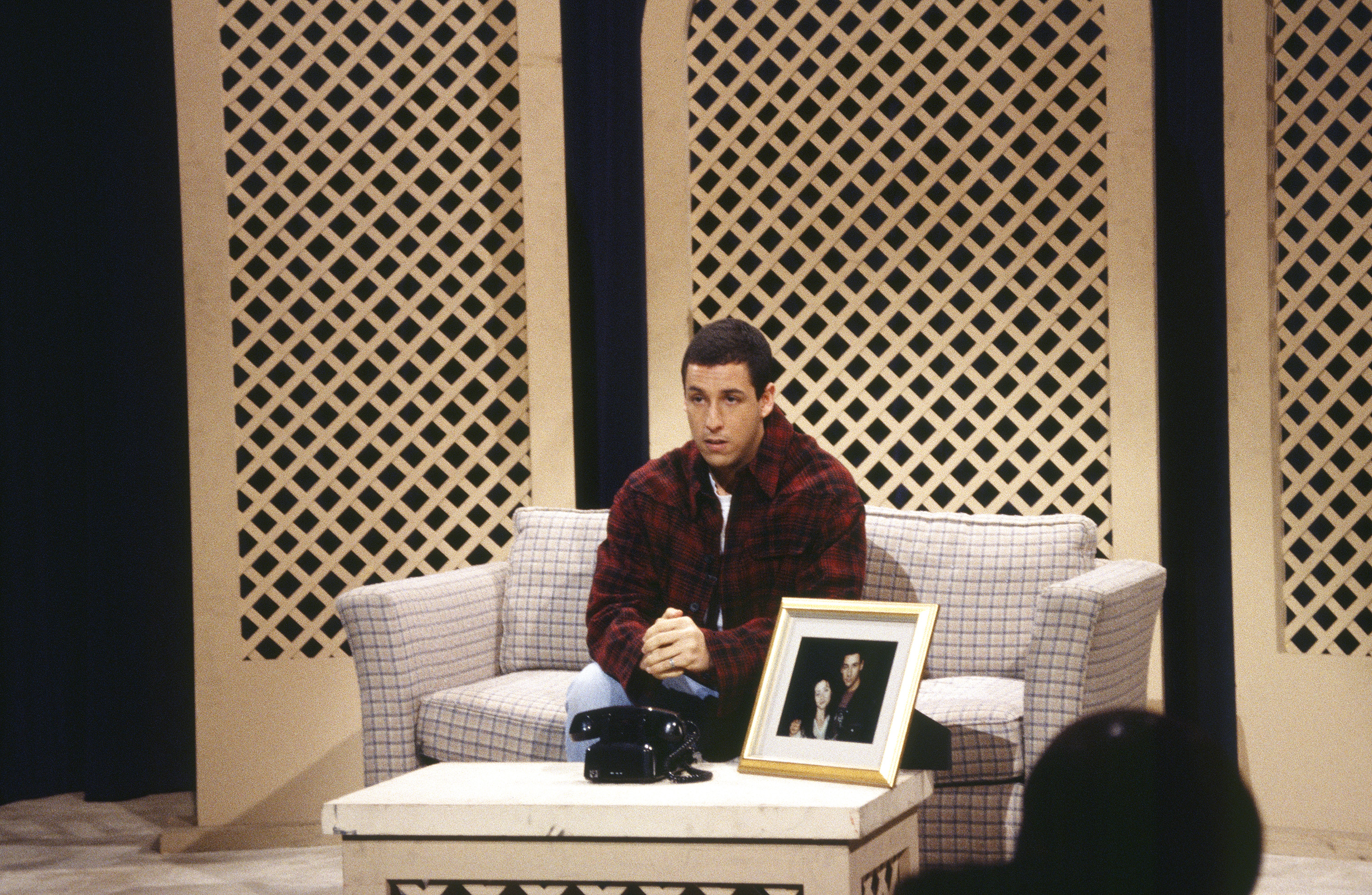

This weekend, Sandler will host the third-to-last episode of SNL’s 44th season. In a statement, executive producer Lorne Michaels said, “We are happy to welcome Adam back to SNL in what is sure to be a special night.” Longtime fans of the musically inclined comic will undoubtedly be tuning in to see what happens. After all, Sandler told fellow ex-SNL employee Norm Macdonald in 2014 that returning to host wasn’t something he wanted to do after reports surfaced indicating he had been fired in 1995. “Why should I? I don’t know how good it would be. I’m slow now,” he said. “I did what I could do on that show.”

Yet Sandler’s return also begs an important question: Is he finally starting to get the respect he deserves?

Sandler has long served as a punchline or, at best, a name you can toss in a snappy headline like “Adam Sandler is awful, and it’s our fault” or an angry Reddit threadfrom people that likely consider themselves arbiters of what’s funny and what isn’t.

Then there’s the matter of Sandler’s comedic oeuvre and its critical reception over the past few decades, which has been mostly negative. “Man-child” is one of many terms that critics have used to describe Sandler’s characters as much as Sandler himself. Others include “juvenile,” “buffoon” and a number of similar descriptors. In other words, his comedy is deemed “vulgar,” in that it’s both unrefined and crude. The thing is, only one of these meanings readily applies to Sandler’s canon.

Sandler has done so much that simply writing all of his work off as lacking in refinement or complexity misses the point. There’s his five-year tenure on SNL, as well as early comedy albums like They’re All Gonna Laugh At You! and What The Hell Happened To Me? An entire generation of moviegoers grew up on films like Madison, Gilmore and The Wedding Singer, in which he played lovable idiots who managed to excel. Others were introduced to Sandler’s more dramatic acting abilities in smaller projects like Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love or 2009’s Funny People, the latter considered an “underrated masterpiece” by some circles. There’s a lot to contend with.

Not everything Sandler has done has been as well-received, or is as well-remembered, as those titles. Many of his more recent Netflix films, like Sandy Wexler and The Do-Over, are some of his lowest-rated projects on Rotten Tomatoes. (The Ridiculous 6, the production of which was plagued by reports of its alleged mistreatment of Native American actors, currently sits at zero percent.) In terms of viewing numbers, these movies and the many others that stem from Sandler’s massive Netflix deal worth $250 million could very well compare to his previous classics. Then again, Netflix doesn’t release viewing figures, so it’s impossible to know for sure how many people are still paying attention.

What is known, however, is the apparent fact that, unlike SNL contemporaries Farley, Chris Rock and Phil Hartman, Sandler’s comedy has never received the acclaim it generally deserves. So whatever happened to the comedian who, as original SNL writer Marilyn Suzanne Miller told the New York Times in 1994, “[filled] up the room” with his “piercing personality”?

Nothing. Or, at least, nothing has happened to Sandler when it comes to what Miller saw in him 25 years ago. From the two Grown Ups films to his and Jennifer Aniston’s upcoming Netflix comedy caper Murder Mystery, Sandler’s comedy stylings haven’t changed all that much. He’s a little older and a bit more weathered, especially when it comes to his opinion of negative reviews, but the comedy itself largely remains the same. It’s big, it’s loud and it’s designed to appeal to the largest swath of people possible. What Sandler does best is nothing like the more inventive and complex works like Tim Robinson’s I Think You Should Leave sketch show or Comedy Central’s acclaimed series The Other Two, and that’s perfectly fine. He’s a modern-day comedy everyman, warts and all.

Except that he never discusses his warts in great detail. At least, not with the press. Sandler has occasionally done interviews, like the ones he did for Macdonald’s podcast and Howard Stern’s radio show, but when it comes to promoting his latest film, he stays off the grid. This is partially due to his disdain for bad reviews, of course, but also because of his fame. Thanks to the celebrity his work on SNL and his first movies created for him, Sandler doesn’t have to do any press to promote his latest fare.

What’s actually changed is Sandler’s fanbase. Those of us who were old enough to watch him come into his own on SNL or listen to his first records are much older now. Others who were a few years shy of this group — the ones who grew up on his “golden age” movies in the late ‘90s and early 2000s — are also entering their thirties. Some have even gone on to become professional critics and comedians themselves, and it shows.

In her review of Billy Madison for the New York Times in 1995, Janet Maslin remarked that Sandler was “at his most bearable” in the film. “Which is to say that the random idiocies and squeaky-voiced singing are kept under control,” she added. “Even if this film doesn’t live up to the absurdist, Groundhog Day-type potential of its premise, it succeeds as a reasonably smart no-brainer. If you’ve ever had a yen to relive the third grade, this must be the next best thing.”

The revered critic isn’t wrong, especially when she compares Sandler to contemporaries of the day like Jim Carrey and Pauly Shore, but her opinion is most interesting in that it reflects a viewpoint that was decidedly more mature than Sandler’s audiences were at the time. This group is now a lot older and more experienced than it was in the mid ‘90s, which means that they’re perfectly able to appreciate and assess the comedian’s latest, even if it doesn’t hold up as well as Little Nicky or Big Daddy do in their memories of them.

Consider Sandler’s recent Netflix special, 100% Fresh. Currently rated at 89 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, the special is one of his highest-rated films in recent memory. By returning to the comedy-album format that solidified his status during the early ‘90s, Sandler successfully transformed his fans’ nostalgia for his older work into something new and, pardon the pun, “fresh.” It’s a collage of stand-up and musical performances from numerous tapings that, much like the albums, smashes together Sandler’s comedic stylings with the occasional assist from friends like Rob Schneider. As a result, critics who were often dismissive of his recent output (myself included) gave him some of his best reviews ever.

Even his alternative output, like Noah Baumbach’s drama The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and the kid-friendly Hotel Transylvania movies, have earned Sandler just as much critical praise as they do audience approval. These are all ensembles of which he is simply a part — but what a part he plays in them.

So in some respects, Sandler has actually been given his due more often in recent years than he was as a young SNL writer and cast member. Sure, the majority of his Netflix projects haven’t fared too well in terms of critical reception, but the wider breadth of Sandler’s filmography has grown to become as respected as it is popular.

It’s almost as if the comic and his work — like the audience that deems their worth — have simply had time to age, eventually realizing a more mature and complex version of themselves. Which is incidentally the theme of every film in the Sandler canon, when you really think about it.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.