On Nov. 23, the baseball world lost Ralph Branca, a big league pitcher best known for his 10 seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers, who was on the losing end of one of the most infamous game-ending plays in baseball history.

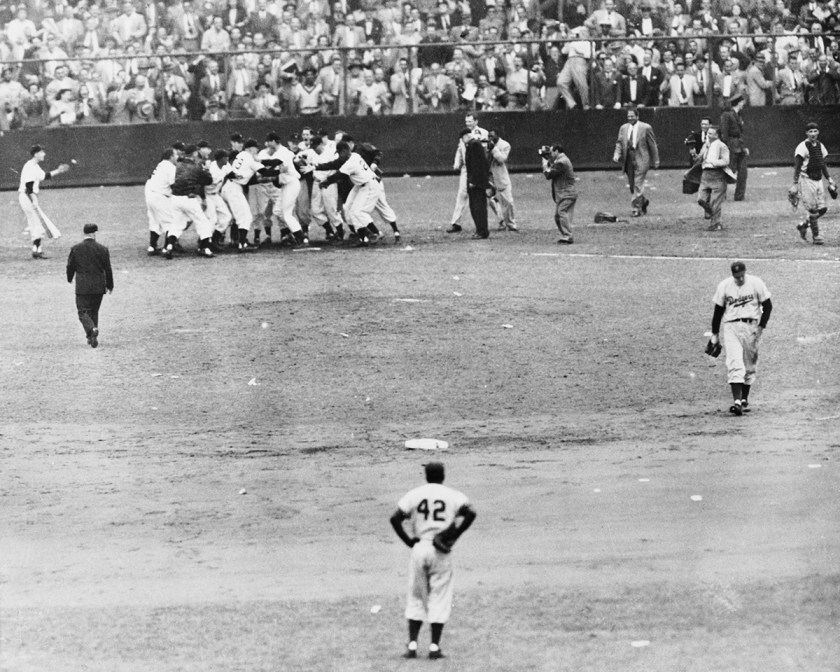

Known as the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” Branca dished up a walk-off home run to New York Giants outfielder Bobby Thompson to lose the 1951 National League pennant—the first-ever nationally televised game of its kind. Millions more viewers than normal were watching Branca’s tremendous failure—including a number of American servicemen stationed in Korea, who would have been listening to the game via radio.

In fact, the moment received one of the most thrilling calls in sports broadcasting history as radio announcer Russ Hodges screamed, “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! It’s the “Butt Fumble” of the baseball world—possibly, the most ego-shattering moment in the history of America’s greatest pastime.

And yet Branca, who lived to the tender age of 90, didn’t let the moment get the better of him. He wore it like a badge of honor, which is something commendable in this day and age.

In looking back on Branca’s career and life, The New York Times‘ Joshua Prager delved into the pitcher’s backstory, revealing a number of interesting nuggets about the Brooklyn Dodger. Here’s Prager on the immediate fallout of the play:

“[It] took him mere hours to find his footing. For after a cold and tearful shower, he had posed his question to a Jesuit priest in the parking lot at the Polo Grounds [baseball field] and received an answer that made sense to him. God had chosen him to endure what was already a blow of biblical proportion, the priest said, because his faith was strong enough to bear it.”

Three years later, notes Prager, another player claimed to Branca that the Giants had cheated, stealing the sign for the pitch, which embittered Branca. Again, he echoed the “Why me?” sentiment. And while the story largely fell on deaf ears in the baseball community, Prager himself reported extensively on the stolen play in the Wall Street Journal in 2001, helping to partially vindicate Branca.

This writer remembers additional evidence from the ’80s or ’90s, when the sports memorabilia world was on fire with young fans, and baseball card shows—giant events where regional and/or national dealers would meet to sell their wares to throngs of enduring collectors—were all the rage. Branca and his “nemesis” Thompson would regularly appear together at shows, signing photographs of the infamous play together. (We have at least one of these dual-signed photos somewhere in our parents’ house.)

For more on Branca’s backstory and incredible mettle, click here.

—Will Levith for RealClearLife

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.