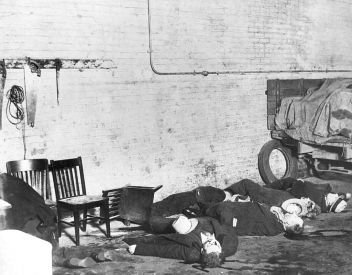

WARNING: GRAPHIC VISUAL CONTENT BELOW

Thursday, bloody Thursday.

It was on a cold Chicago morning 90 years ago today when four men – two of them dressed as police officers – burst into a brick garage on the North Side and told the seven men inside 2122 North Clark Street to line up against the wall.

Ninety bullets later, all seven were dead or dying and the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was complete.

What led up to the infamous mob shooting? Here’s how how it all went down on that fateful Valentine’s Day nine decades ago.

In early 1929, Prohibition was going strong in the United States rival gangs in Chicago were at war over control of the city’s bootlegging industry as well as the gambling and prostitution side businesses.

On opposing side of that turf war were Irish gangster George “Bugs” Moran of the North Side and Italian mobster Al Capone of the South.

Though they’d been fighting over territory and control of the city’s illicit businesses for years, the battle between Capone and his longtime enemy reached its bloody climax after a failed assassination attempt by Moran on a gent named Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn failed.

Angered by the attempt on his life, McGurn approached Capone while he was on vacation in Florida and said he had a plan to rub out the Moran gang and was willing to execute it as long as the future Alcatraz resident would fund the operation.

After Capone agreed, McGurn set wheels for the Massacre in motion.

In order to make sure the hit wouldn’t be traced back to Capone or his gang, McGurn outsourced some heavy hitters from outside the city and then set up a deal via a third party to buy some hooch from Moran at the S.M.C. Cartage garage, his bootlegging warehouse. To make sure there was no funny business, McGurn’s hoods rented a room at a nearby rooming house to spy on Moran’s garage.

The deal on offer – $57 a case for Old Log Cabin whiskey – was too good to refuse and the two sides arranged to meet on the morning of the 14th and exchange liquor for cash.

With Capone still in Florida, the quartet of hired guns, two of whom were dressed as police officers, arrived at the North Clark Street address and acted as if they were conducting a raid upon entering the building.

Expecting a simple bucks-for-booze transaction, the seven men inside the garage, including Moran enforcer Frank “Hock” Gusenberg, his brother Peter “Goosy” Gusenberg and a thrill-seeking optician named Dr. Reinhardt Schwimmer, treated the intrusion as if it was a standard shakedown and complied when they were ordered to line up against a wall.

Courtesy of the counterfeit cops and their plainclothes peers, the seven gentlemen against the wall had their backsides introduced to a hail of bullets from submachine guns.

With the smoke still clearing, the gunmen walked back to their siren-equipped black Cadillac touring car with the phony officers acting as if the other two men were the perpetrators of the shooting for the benefit of onlookers who had gathered. Once inside the car, they sped off.

It was a seamless plan, except for one thing: Moran wasn’t inside.

Having slept in that morning, Moran was late to the meeting and, upon seeing the siren-equipped Caddy outside the garage, he assumed a sting was going down and beat feet away from the scene.

Though Moran escaped the shooting intact, his criminal empire did not and Capone and his successors would go on to run organized crime in Chicago for years.

A few days after the killings, Moran told reporters “Only Capone kills like that.”

Capone, when reached in Florida, took a shot of his own: “The only man who kills like that is Bugs Moran.”

Ultimately, authorities couldn’t determine if it was Capone, Moran or anyone else who was responsible for the gangland slaying and no one was ever brought to trial or served time for the cold-blooded killings.

“These murders went out of the comprehension of a civilized city,” the Chicago Tribune editorialized at the time. “The butchering of seven men by open daylight raises this question for Chicago: Is it helpless?”

On a Thursday in mid-February in 1929 at least, the answer was yes.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.