Recently, a lot of people fiddled with their ethereal bunny ears and dialed up the Netflix to watch the disturbing Motley Crüe biopic, The Dirt.

With the hoopla over the Crüe crew and the rabid success of Bohemian Rhapsody, it is very likely that we are teetering on the edge of a new wave of rock biopics.

Your friend Tim has mixed feelings about this trend.

Like jukebox musicals (my god, there are so many of these!), the appeal of rock biopics is very easy to understand: We know the stories, which are full of sex, tragedy, and glamour. We know the songs. The costumes make us giggle. Sometimes, there is nudity involved.

Biopic or jukebox musical, most of know we are seeing factually specious cat poop, but it reminds us of a time in our life when we didn’t worry so much about mortgages or whether our kid was going to get killed by the Uber driver.

So stick any damn story up there, just get people singing along and leaving the theater with a rousing chorus suck in their head.

Mind, you, rock biopics are nothing new. From La Bamba, The Doors, The Buddy Holly Story, Walk the Line, Great Balls of Fire, to more artful and obscure treatments like Control and Backbeat (not to mention catastrophes like London Town), these things have long been an easy and lazy way to draw audiences of a certain demographic, with truth usually left outside the multiplex.

Funny — and I am somewhat alone on this, especially amongst the rock crit community — I loved Bohemian Rhapsody. (We won’t discuss The Dirt, for about eight hundred reasons; suffice to say that it portrays women as badly as Birth of a Nation treated African Americans, and it makes Mariah Carey’s Glitter look like Roma).

Bohemian Rhapsody was a bright, catchy musical, and a lot of fun to watch. Of course the facts were all over the place — so much so that great spans of the film are pure fiction — but it was a fun, moving movie with great songs. Also, unlike the Motley Crüe film, the facts it altered did not minimize the band’s role in murder, assault, and sexual abuse.

All rock biopics require rather massive narrative short handing for dramatic effect, radically adjusting facts and omitting differing (and frequently legitimate) interpretations of events. For instance, the otherwise excellent Love & Mercy was profoundly shaped by the characters who authorized it. The best music biopics, perhaps, give a somewhat surrealistic impression of a place and time — like my favorite non-fiction music film, 24 Hour Party People. You are always going to get f*cked if we expect a standard rock biopic to actually tell the real story.

That’s okay. No one seeing The Sound of Music is going to come away with a full understanding of how Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg’s weakness and indecision contributed to Austria’s annexation by the Third Reich…yet there’s no bloody Sound of Music without that event. But that doesn’t matter for the movie-going enjoyment, does it?

The truth of bands is boredom and deceit.

Boredom is, well, long and boring. So who wants to watch that on the screen? And the deceit is hard to film. That’s because these betrayals are either terribly complicated — try explaining the vagaries of music publishing or merchandise splits to someone unfamiliar with the music business — or they’re completely petty. Most bands fight (and break up) about stupid nonsense like who gets to sleep on the bed instead of the couch, or whether to stop to eat right now or two exits from now.

This sort of crap dwarfs fun stuff like stomping your feet and writing “We Will Rock You.” A truly realistic rock film would show a band sitting in a diner waiting for their food. Then the bassist would get the wrong food and send it back; then the singer would scream at the guitarist because she took a french fry without asking; then the guitarist and the drummer would scream at the singer for not helping with last night’s load-out; then the drummer would go outside for a cigarette, realize he was out of cigarettes, and come back in and fall asleep at the table. That sort of thing would happen over and over again for four or six hours, and then the final credits would roll.

That sounds a lot like a movie or Wim Wenders film, doesn’t it?

In fact, I have long thought that one of the best rock’n’roll films ever made was Wenders’ 1975 Im Lauf Der Zeit (the English title of which is Kings of the Road), which is basically just two and half hours of guys driving around listening to rock’n’roll and not talking. Nothing happens, other than the occasional argument. See, that’s a real rock’n’roll story.

Likewise, Wenders’ 1974 film, Alice in den Städten (Alice in the Cities),chronicles a character who is vaguely artistic, and traveling thousands of miles with a mostly silent companion. Not a lot happens, other than the fact that the companion lies sometimes. In other words, it is exactly what it’s like to be in a rock band.

The simple Hollywood approach to the rock biopic is to just focus on a death and work backwards (like Bohemian Rhapsody, La Bamba, The Buddy Holly Story, and the Doors.). The rash of rock biopics to come, I suspect, will highlight stories back-loaded with death, even when the death is a stupid and distracting part of the story (for instance, Sid Vicious is the least interesting thing about the Sex Pistols, but he’s likely to be the focus of any film about the band).

Here’s another important reason I believe there are going to be more and more of these things, and why we may think we “need” them:

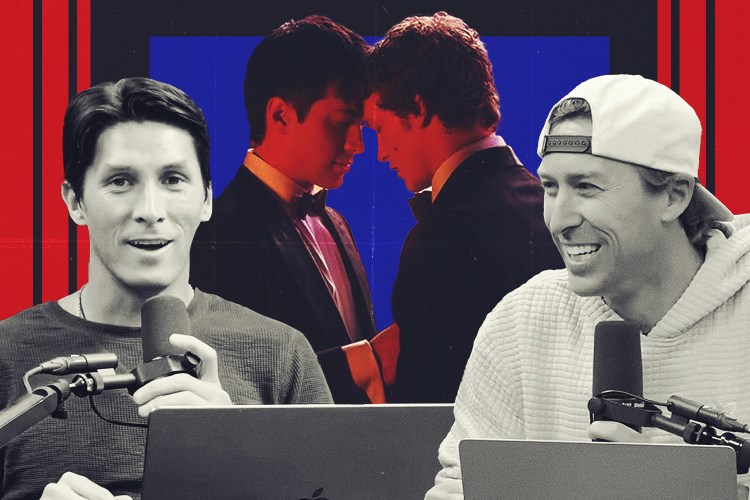

The era of English being the dominant language — the lingua franca, to use the fancy term — of pop is disappearing. In the near future, heck, before I finish typing this sentence, the marketplace will be driven by Koreans, Japanese, Chinese, and Spanish language acts.

As English loses it’s grip on pop, as rock becomes more factionalized, and as an older generation of listeners refuses to latch on to the plethora of fascinating new rock acts, there is a perception that “rock” is a thing of the past. So a simple way for us to form some link with our identity as “people who like rock” is for us to endorse the rock biopic as a common mode.

If we don’t have new bands or records to talk about, let’s find a new way to engage with the old ones.

(Side note: Rock is far from dead; but an older generation of music fans, addlepated by the dizzying plurality of Spotify and YouTube – where to start, where to start?!? — has generally been unwilling to look under the rocks where the spectacular new-ish rock bands reside. We no longer have MTV or the old school FM powerhouses to guide us. This has given many older fans — and journalists — stuck in their Eagles/Floyd/Springsteen rut, the mistaken impression that rock is dead. Rock is not dead; it has just fragmented, gone tribal, and gone underground).

These biopics connect an older generation — that is to say, anyone over 35, but especially over 45 — with their cultural history and social legacy, and keep them actively involved in, oh, the mysteries of rock, and the idea that they are still rocking people, regardless of their age and the advancing years of their heroes.

So bring ‘em on. Just tap your feet, enjoy the ride, and leave the fact checking at the door.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.