In broad strokes, Scott Derrickson’s new film The Black Phone sounds like the paranoid night terror of a parent about to send their offspring on a solo walk to school for the first time, their fears stoked by the 10 o’clock news. Neighborhood kid Finney finds himself in the clutches of a deranged child abductor known as The Grabber, already rumored to be behind the disappearance of five other locals who fell victim to his knockout-gas-and-van routine. Locked in the sadist’s basement, our boy must contrive a way out before he meets a gruesome fate, his only assistance coming from a cord-cut phone through which he can speak to the spirits of those poor souls who have faced this same plight. With some spectral pointers, he jerry-rigs a daring escape attempt — but will he be too late?

Finney’s trial-and-error search for a path to survival requires him to think creatively, considering new angles with each approach that winds up in a dead end. His ingenuity is synonymous with that of screenwriters Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill, adapting Joe Hill’s short story and sharing in his goal of throwing up hurdles only to help the protagonist clear them. This new entry in the small canon of locked-door horror — films stranding one or more characters in an enclosed space and challenging them to think outside the box (sometimes literally) to earn their freedom — illustrates the difficulties and pitfalls inherent to this mini-genre. A limited location, a restricted number of characters and a narrative model rooted in sparseness all demand finesse in order to be spun into feature-length cinema, and The Black Phone shows why, for worse more often than for better. Isolating its teachable flaws and looking back on the high points of the form, we’ve outlined five basic tenets for successful locked-door horror, for the aid of amateur scribes and terrified captives alike.

Set your rules (and stick to them)

If someone locks someone else in a cell meticulously constructed for absolute impregnability, there’s usually a point to all the hassle. It’d be much faster and easier for the psycho at hand to just snuff out their quarry and be done with it, so they’ve generally got a fiendish game to be played before that can happen. Whether dictated explicitly by the villain of the film or tacitly by the writer’s pen, a set of rules and specifications take shape to guide our hero(es); if followed to a T, the characters in peril may just make it through the night, while breaking them tends to spell instant death. And the same goes for the filmmakers, their work doomed if they don’t adhere to an established internal logic consistently through the duration of the script.

In The Black Phone, for instance, the abilities of the ghost-children contacting Finney seem to come and go when dramatically convenient. They state in no uncertain terms that they can’t just do away with the Grabber themselves and must rely on Finney to avenge them, yet they possess telekinetic powers enough to move a Sprite bottle around. Sometimes, they manifest visibly to Finney, for no other reason than it gives viewers something to look at in a film nervous about its own inertia. The best counterexamples can use the continuity of rules as a weapon to be marshaled against evil, as in the third installment of mini-genre staple Saw. When the obsessive black-and-white moralizing of the original Jigsaw killer is sullied by the unchecked malice of his latter-day successor, the offender must pay the ultimate price in a second twist stacked atop the first for a genuine surprise. Cruel yet impartial gods govern these savage universes.

Choose your obstacles carefully

In the tradition of locked-door horror, the word “unfilmable” will sometimes be thrown around as a euphemism for a concept too sedentary or too dependent on the interiority of the written word to be translated to the screen. Of course, everything’s only “unfilmable” until it’s filmed, proof that it’s all just a matter of not painting one’s self into a corner. This type of premise thrives on diligence, the assurance that the writers have tested every chink and weakness in the airtight environment, just as the character desperate to free themselves would (as well as the discerning, critical-minded viewer). As such, the obstacles put up by the screenplay must be able to withstand close scrutiny. If we can figure a way out before the characters do, the movie falls apart. 10 Cloverfield Lane barely takes interest in the security of the subterranean bunker where John Goodman holds Mary Elizabeth Winstead, more concerned with the easily answered question of whether aliens lurk outside. Her escape lands beside the point, and makes us wonder what it was all for.

Metaphysics can get the job done, as it does in Vincenzo Natali’s In the Tall Grass (a King/Hill father-son joint), which cuts through the Gordian knot of its “people can’t leave an endless field” setup by drawing on time loops and supernatural influences. More commonly, it comes down to thinking of every last thing; take Natali’s most well-known film, the diabolical Cube, in which a massive three-dimensional booby-trap-laden maze must be solved like an equation. Precision, order and exactitude are the name of the game, enabling us to race along with the six test subjects as they calculate their way to the endpoint. The Black Phone, conversely, falls apart when poked. The Grabber is an exceptionally sloppy operator, for starters in his choice to situate his child-prison in a basement-level room with a window exposed to the street. Even if Finney can’t reach it, he’s visible to the outside world! It’s a wonder the Grabber nabbed six kids before getting caught.

Be brief with backstory and B-plot

The prospect of spending 90-or-so minutes in a single setting is enough to scare off plenty of writers, or perhaps more importantly, financiers and producers. Everyone’s worst fear is boring the audience, and so diversions take us away from the main story to break up what could otherwise risk monotony. These can come in the form of flashbacks explicating the origins of the imprisoned characters, who seldom land in such a predicament at random, more frequently selected to learn a grisly lesson the hard way. The other option is a secondary plot taking place beyond the limits of the confinement, often tracking the investigation or rescue effort developing on the outside. In The Black Phone, we check in with Finney’s possibly clairvoyant, possibly schizophrenic (just like Mama!) little sister as she scrambles to decode the visions that come to her in sleep with no help from the classically useless cops. In her too-clever-by-half dialogue and repetitive head-trip montages, these scenes mostly gum up the works, a tiresome distraction from Finney’s more pressing breakout.

These tangents wield the greatest impact when kept swift and purposeful, if included at all. (The most self-assured entries eschew the other stuff entirely, like the chillingly matter-of-fact Old, an open-air inflection on the concept.) In Gerald’s Game, a Stephen King adaptation reiterating locked-door stories as the King/Hill family business, a husband handcuffs his discontented wife to a bed and promptly drops dead of a heart attack, leaving her to confront the lingering trauma from a girlhood sexual assault at the hands of her father. Director Mike Flanagan portrays this formative moment with a striking shot bathed in lurid, foreboding red by a solar eclipse, the ambient menace of the style communicating more than blunt-force exposition could hope to. Like her, we’re snapped back into reality out of a memory made more vividly severe by time, as well as the brevity of our glimpse.

Won’t somebody think of the captors?

If Stephen King owns the locked-door story, it’s because of Misery, Rob Reiner’s 1990 film being among King’s favorite treatments of his own work and still the only one to have netted an Oscar. Its popularity ultimately boils down to the brilliance of the Annie Wilkes character in conception and execution, a vindictive, violent superfan played by Kathy Bates as a combination of teenybopper and sweet old grandma. King and Reiner don’t shy away from the obsessive side that moves her to smash the ankles of the novelist she’s taken prisoner, but they also take time to consider her humanity as a loner only capable of connecting to the world around her via his literature. Bates brings out the immaturity in Annie’s arrested development, her inner pain as a disturbed woman, her imperiousness and her hysteria — all the things that, when mashed together, form the contradictory array of traits that make up a human.

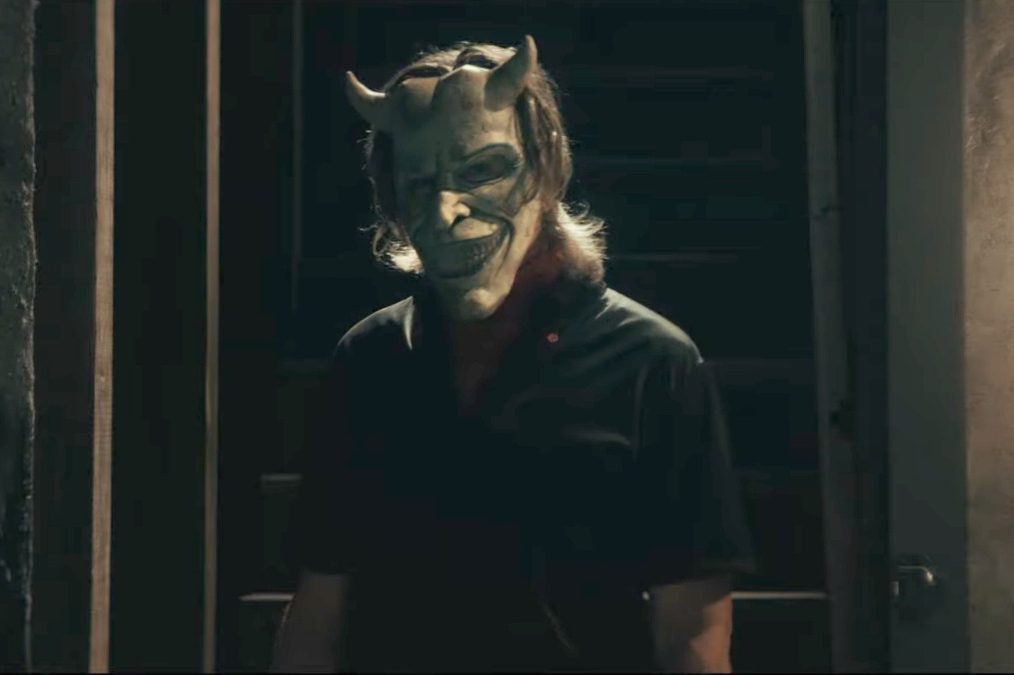

She’s an object lesson in the importance of lending as much psychological depth to the villain as hero, in the understanding that a real baddie doesn’t think of themselves in those terms at all. Being able to muster a measure of compassion for the boogeyperson running the demented show ups the tension all around, lending real stakes to the pressing matter of whether they’ll get away with it. The Black Phone gives us precious little along these lines, writing the Grabber as a self-evident force of malevolence who seems more underdeveloped than enigmatic. His motivation for snatching up youngsters seems no more complex than garden-variety pedophilia, albeit with a more involved schtick attached. The happy-or-sad devil masks and Ethan Hawke’s affectation-heavy physical manner do all the work, reducing a significant piece of the dramatic formula to a collection of quirks and habits rather than a comprehensible (or disturbingly unknowable) mortal soul.

Less is more

Chekhov works overtime in The Black Phone, which arms Finney with an arsenal of objects refashioned as makeshift weapons in his one-boy war on the Grabber. A helpful phantom points him to a cable that can be used to grapple up to the bars on the window, though it comes crashing down. Perhaps he could still amble up there by climbing up one of the numerous mattress topper pads inexplicably stacked by the toilet (which still has its lid), or the mattress itself. Or once he’s learned the lock combination from another ghostly pal, he could slash the Grabber with the pointy toy rocket he’s been allowed to keep, if not one of the many glass Sprite bottles he could use for any number of counteroffensives. The accumulation of objects makes matters messy in a nevertheless overdetermined script, each prop getting its obligatory big moment following a conspicuous introduction earlier on. It feels like the deck has been stacked in Finney’s favor, even if he’s in a quandary no one would envy.

The minimalist spirit of resourcefulness should begin and end with the camera, the most valuable tool when trying to expand the potential of a finite space. Finding novel angles from which to view the scene can bring out notes of hopelessness or resilience, more effective when visually modeled than stated outright. Buried traps Ryan Reynolds in a coffin underground and seems to give him everything he needs, a starter kit including a knife, a lighter, a glow stick, a pen, a flask with booze, and a BlackBerry with which to contact the world above ground. As this all proves useless, however, director Rodrigo Cortés emerges as the truly crafty one in how his cinematography captures the claustrophobia without getting stuck itself. Audiences prize locked-door stories for their wits, the Hitchcockian mounting of anxiety in a pressure-cooker set. As much as we may want to see the hero escape with their hide intact, going easy on them robs the viewer of that cathartic pleasure. They’ve got to be put through hell before they can be salvaged, no narrative handicapping necessary.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.