It feels like a gross understatement to say that music and place are inextricably linked. Where artists are from can inform everything from how their voices sound and the and the words they choose to the particular worldview they espouse with their material. Certain places are hotbeds, home to thriving local scenes, and others — like Muscle Shoals, Alabama, home of the Swampers (including David Hood, father of Drive-By Truckers frontman Patterson Hood) — have some sort of intangible magic to them that finds its way into the songs and prompts some to theorize that maybe there’s just something in the water.

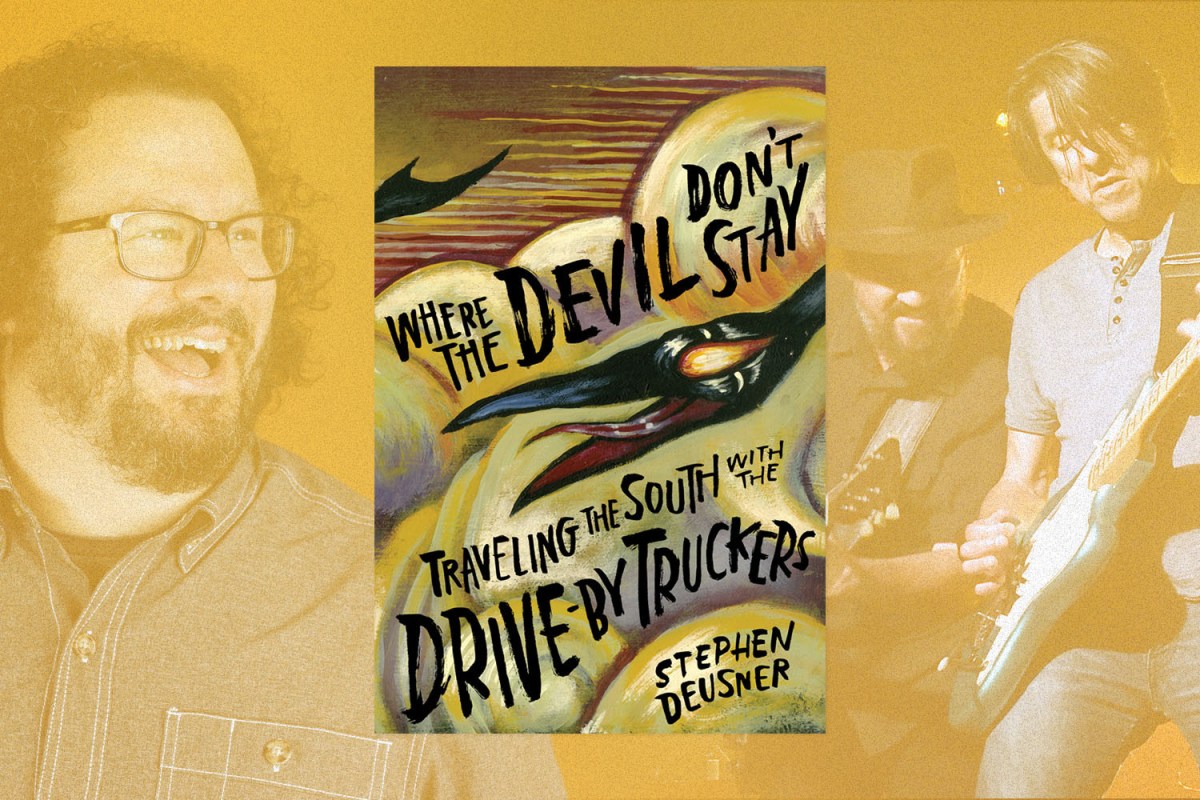

It makes sense, then, that for his excellent new book Where the Devil Don’t Stay: Traveling South With the Drive-By Truckers, author Stephen Deusner decided to focus on place rather than writing a traditional band biography in chronological order. Each chapter is named for a particular locale that played a significant role in the beloved Southern rock band’s history or catalog, making it part biography and part travelogue. Along the way, he examines how the band has wrestled with its Southern identity over the years, whether it’s through songs like “What It Means,” penned in the wake of the Michael Brown murder, or Hood’s thoughtful and regretful op-ed last year about the racial implications behind the band’s name or his eventual move to Portland.

We caught up with Deusner to find out more about that, his own personal connection to one of the book’s chapters and all other things DBT.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell me a little bit about what inspired you to organize this book by place and location rather than presenting it as a traditional chronology.

Stephen Deusner: Well, I think originally when I first thought there could be a book here, a long time ago, my first thought was it would need to be chronological. But then, the more I sort of lived with the songs and went back through some of their older material — actually, I was living in England for a little while. I would just walk around Birmingham, playing some of their records. I think being over there, being so far away from home, it made me realize there are a lot of place names in these songs. So I started thinking about them in terms of place. I knew that their story took them to a lot of different places, both physically and just lyrically. It seemed like they were talking about these places in very specific ways, and I wanted to really explore that. So, that kind of became a way in and a way to sort of distinguish it because, I mean, they’ve been going for 25 years and I think they could go for another 25. So I felt like a chronology would be necessarily truncated. I thought this just seemed like a better way to go about it, especially for a band that is still adding very exciting installments to their catalog.

How did you go about deciding which specific places you would include? For example, the Memphis chapter I think is one that is maybe not one of the first places that people, unless they’re more diehard fans, are really familiar with being part of the band story.

That’s actually a really good question. I’d say slightly different ways. I mean, Memphis, that’s where I got my start writing about music. My editor at the Memphis Flyer, a guy named Chris Harrington, who’s actually a really good music writer, I think he covers basketball now, but he turned me on to the band. I remember he wrote this piece that sort of mentioned that they had lived in the city and that stuck with me. They had this kind of local connection. This is after I had moved away from Memphis. So, I think that always stuck out to me. And then you hear a song like “Carl Perkins’ Cadillac” or “The Night G.G. Allin Came to Town,” which is … I mean, I’d heard people talk about that show even before I heard that song. Even something like “One Of These Days,” that song where there’s a line about Memphis being hell on earth, that seemed like there were enough clues there that, that made that particular place seem important. Obviously, I’m from Selmer and the first interview I ever did with Patterson, we talked about McNairy County and Buford Pusser. So that one also stood out to me as well.

But the others, I mean, it was just kind of going where the music took me. Obviously, I’m going to want to write about The Shoals, not only because that’s where they’re from, but that’s what they wrote about. They wrote about that the way the Ramones write about New York or something, or Lou Reed wrote about New York. That had a profound impact, to hear about some of these obscure places that I knew, but that never got talked about in rock songs. I think the weirdest one was Richmond because that was not one that I had going in or I had given much thought to. That city kept popping up in interviews that I had with Wes Freed and with Mike Cooley, in particular. I think he’s the one who was like, “That’s where we really had an impact, was in Richmond.” So, that was kind of fun that that kind of jumped out and kind of demanded to be written about. Birmingham was the last one I wrote because it wasn’t in there for a long time, but it felt like something was missing, and I kept trying to figure out. I hadn’t had a chance to really dig into the making of Southern Rock Opera. So, once I kind of thought, “Okay, I’ll just do something on Birmingham,” it actually kind of wrote itself. I have no memory of writing that chapter whatsoever. Which I hope doesn’t reflect on the quality of that chapter, but it just kind of came together in a way that I think back on it, was weirdly like a bit of sorcery or something. I was channeling some sort of demon. Maybe that’s not the right way to put it, but you know what I mean.

You mentioned the McNairy County chapter, and obviously you’re from there. Did you go back and forth about how much of your own personal experience you wanted to include in that chapter, or was that something you knew right away going in that you wanted to include?

That was something that I kind of negotiated with myself and with the material, pretty much the entire process. It started out with a lot more about me. I whittled that back and whittled that back a lot. But I think that was good because it really kind of surveyed my own experience as a Southerner and as a fan of this band, to sort of at least have that material and to know where I stood. So it was a really good exercise. I knew that the Selmer chapter had to be included, but also had to be very first-person. Same with the Birmingham one, but by then, I kind of had an idea of how to bring that material in. But with Selmer, it was really a lot of, negotiation just with myself, just trying to figure out, “Does this really belong? Is this too much? Is this too much, just that breaks up the flow?” But also just, I didn’t want it to be one of those books that becomes more about the writer than the band. So I was very hesitant to put myself too far into it because I don’t want to bore people. But on the other hand, I do think just dealing with fans of this band, it’s obvious people have similar stories to mine. So it felt like that was another thing that was prompting me to include some of that first-person material like, “no, everybody does this. This just makes it more relatable on a whole.” So yeah, there were a few things that I ended up cutting and a couple of things I wish I’d included in the end, that were less about me and more about just my relationship to my hometown.

In the book you mention how it was 2003 when you first listened to the band, because you had initially been put off by their name. Was there a moment when you finally listened when you realized, “Oh, this is actually not at all what I was expecting”?

Well, I think as soon as I listened, it didn’t sound like what I was … I expected something that was more in line with their earlier work, like their first album. That was very alt-country and kind of jokey. I’m really glad I did not hear that album first. I love that album now, but only because I came to it later. I remember specifically hearing the beginning of “Marry Me,” where Cooley does that incredible boogie rock guitar riff that is obviously very ’70s but also felt very fresh for what was going on in guitar rock at the time. It was just like, “Oh, there’s something else going on here.” I remember there was a line from “Sink Hole,” where Patterson says something about nana pudding. That was a phrase I had not heard in 20 years or something. It was just like, that phrase, those words, that’s such a specific Southern thing. That was something that took me back to my own childhood and to my own experiences in the South in a way that was very, very vivid and evocative. I just remember thinking, “Not just anybody would use that phrase. This guy knows what he’s talking about. This is not just a bunch of guys in a rock band. This is somebody who’s really attuned to a certain kind of experience.” I think those two songs on Decoration Day were the first time I was like, “Yeah, this is something that I’m going to really want to dig into.”

In the intro chapter, when you’re talking about American Band and “What It Means,” you reference the line “the duality of the Southern thing.” And then towards the end of the book, I think you have a line about how the South is becoming more like the rest of America and the rest of America is becoming more like the South. How do you think that that impacts the duality of the Southern thing? Do you think that duality will always be there?

I do. I mean, especially with what’s going on right now with Afghanistan, that represents 20 years of American intervention that I think all along was misguided. And what’s going on with the vaccinations, which a whole group of people has decided not to get it, for reasons that don’t make very much sense except cultural or political obstinance. I mean, I think that duality is more pronounced for me. I think it’s helped me kind of weather the last couple of years. Because I think, coming out of the South and realizing that this place that I love and this people that I love and this culture that I love, is embedded in this history that is incredibly ugly. How do you deal with that? How do you balance those two? I think that’s the genius of American Band, is that they expanded that and really set that idea to apply to the entire country. That’s something that I keep coming back to a lot lately, is that duality. I love America and I love rock and roll and all the music that is identified as American and all the culture that is identified as American. At the same time, I realize that this is a country that has a dark and ugly legacy in a lot of ways. A lot of ways it doesn’t, and a lot of ways it does. So I think that’s kind of helped me come to a good place, where I can see both sides. I think that’s helped me become more active. There are things worth saving. There are things worth being radicalized or activists about. So, I think it’s helped me take steps to at least try and make it better, or at least try to make my little corner of it a little bit better.

Sort of related to that, you end the book on the idea of leaving and leaving behind. I’m curious how you think the Athens Homecoming shows fit into that concept, because it’s sort of like they leave, but then they always come home. How does that fit into your thoughts on the Truckers being a little bit nomadic and moving around from place to place?

Actually, that’s a really good point. I hadn’t really thought of it in those terms. It is about leaving, but it’s also about coming home again. I guess you could sort of apply that to the whole sunset, what’s on the other side of the next sunset, that sort of thing that I wanted to end with. Homecoming, it has become a time to mark these departures. They still dedicate songs to Craig Lieske, who was their merchant guy who died, I believe it was the night before Homecoming, very suddenly. It startled a lot of people and obviously saddened a lot of people. He is someone they still commemorate. Same with Vic Chesnutt, same with a lot of people who have been with the band and aren’t with the band or some of those old Muscle Shoals guys or something like that. There’s a lot of commemoration of those departures at Homecoming, but I think that you’re right. I think it is a renewal. I think it’s like a renewal of this relationship between the band and the community that’s kind of gathered around it and people like me, who have these stories that apply to the music. I think that is one of the most crucial aspects of their longevity, is not just the Homecoming shows, but what it represents for their fans and the community. So I think that’s super crucial.

In researching and doing interviews for this book, was there anything that really surprised you or caught you off-guard?

I will say, I think one of the things that did surprise me was the sort of depth of their dysfunction at the end of the Isbell years, the depths of his addiction problems, the severity of his marriage with Shonna. Those things I knew, sort of from a very dry kind of … I’d read about them, but you don’t know until you actually talk to people and try to write about it, just how dark it got. People were very forthcoming about their behavior during that time, not just Jason, but a lot of other people as well. I think seeing how bad it got made me realize how amazing it is that the band is still around and still making great music, but [also] that Jason has had this incredible success as a solo artist. He’s gotten sober. He’s not only gotten sober, but he’s turned that into material for songs that create this incredible connection with his fans. So, they’ve used that, those bad experiences, for something really good. They’ve turned it into something that is very meaningful. Maybe that didn’t surprise me necessarily, but I did grasp the magnitude and importance of that turnaround.

Speaking of Jason Isbell, one of my favorite quotes in the book from him is when he’s talking about why he stopped trying to sing like Otis Redding. He was basically just like, “Because I’m a white person, I don’t have the lived experience to sing like that.” He has this really great self-awareness that all of the Truckers do, of just sort of who they are and their privilege and their background.

I don’t think they ever tried to write a song that would end racism. I don’t think they ever tried to write a song explicitly about a Black character because they don’t know that experience. I mean, that’s a thing that is easy to overlook and kind of hard to overstate, because there’s a sense there that they know what they can do and what they can’t. I mean, even with the allusions to Southern hip-hop, those are just references. I mean, they’re an acknowledgement of influence, but they’re not trying to own any of that, necessarily. I think that’s really, really crucial, their awareness of what it means for them to be in a Southern rock band and what the stereotype of that would be. I mean, immediately, they’re trying to distance themselves from the Confederate flag. That’s not a new thing, by any means. That was pretty much baked in, almost to who they were when they started. I think you also see that a lot in what Jason is doing now, with the vaccination policies for his shows. He knows that a lot of people are looking at him. It might be easier to just ignore it and hope for the best, but more power to him, that he is sticking up for that. I think that’s incredibly important right now. I just can’t even begin to say how much I appreciate what he’s doing or respect him for how he’s doing it.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.