Joe Hale wasn’t trying to get paid — the thought hadn’t even occurred to him. He just wanted to come inside and snap some photos. He’d first shot runners at the age of 18, on a lark, at Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. An older friend of his, a former cross-country teammate who now ran for Siena College, lent him a DSLR and asked him to capture the race. Shooting on auto the entire time, Hale had a blast. Afterwards, he saved up for months to buy himself a Canon Rebel T5i.

But now, a little bit older, he wanted entry to The Armory (officially the Nike Track & Field Center at The Armory), New York City’s century-old, neoclassical indoor track mecca. The one with the banked Mondo track, where pros run the mile in under three minutes and 50 seconds. Once the venue’s social media manager, Billy Cvecko, finally relented, Hale never left. He spent the winter weekends of his freshman and sophomore years at Manhattan College at the track, taking photos for 10 hours a day, no matter the event.

The Armory hosts more than the Millrose Games, after all; it’s a constant campground for backpacks and sweatsuits belonging to every iteration of adolescent runner: the highly recruited elites, the glue guys, the freshman prodigies, the parents-made-me-do-this set. Hale shot everything from Class D action to the Wanamaker Mile, and over time he met a lot of people.

“Pros, elite high school and college athletes, coaches, brand people, you name it,” Hale says. “[Including] Kyle Merber, who was a Hoka NJNTYC [New Jersey-New York Track Club] athlete at the time, and Sam Parsons and a bunch of the Tinman Elite guys. I started shooting NJNYTC practices shortly after, since they practiced directly across the street from my dorm. I also stayed in touch with Sam virtually.”

Hale was already planning to spend the summer of 2020 in Boulder, Colorado, but when COVID hit, he found himself unusually free. He reached out to Tinman Elite (TME). The professional running team was founded in 2017 by Drew Hunter, a onetime high school phenom looking to relaunch his career alongside his fast friends; by 2020, the group was pioneering a contemporary strategy for funding its runners’ (expensive) Olympic dreams: making YouTube videos and selling caps and tees with an axe logo, a nod to the adage “chop wood, carry water.”

“I made my services available to them,” Hale says. “[I] told them I’d love to help out any way possible.” At first, that meant folding T-shirts and taking photos a few times a week. But over 16 months in Boulder, Hale says, “my network in the sport of running was essentially built.” Slowly but surely, he started photographing the elite runners who were in town for the summer, testing their mettle at altitude on Boulder’s endless foothills. From there he’d go straight to TME’s practice, where he’d also bump into runners from Team Boss, Roots Running Project or On Athletics Club (OAC), which was then still an unvarnished upstart on the scene.

Hale counts his summers in Boulder among the best of his life. They left him with lifelong friends and a core lesson: “Running is an extremely small community. You can be a crew runner and be one connection away from an Olympian. The spiderweb is super tight. Just being at various events is the most important and efficient way to meet people and expand [your] network.”

Four summers later, Hale found himself at the biggest running event of them all, shooting the likes of 1500m champion Cole Hocker at the Summer Olympics in Paris. Throughout 2024, he has also taken photos of track athletes at Switzerland’s Weltklasse Zürich, middle-distance runners at New York’s 5th Avenue Mile and sprinters at the inaugural, female-only track and field series ATHLOS. He’s shot competitors from different sports, too: U.S. Open champion Aryna Sabalenka drinking a smoothie; Jalen Brunson under the warm lights of Madison Square Garden.

Still, Hale estimates that 75% of all the photos he’s ever taken feature a runner. He has, through a combination of resolve, timing, talent and passion (and we’d have to assume, a little bit of luck) become a “running photographer.”

That sounds too specific, a little made-up. But while Hale’s path is unique to him, he’s far from alone in his vocation. As the running community expands ever-larger, riding its biggest bonanza since the late 1970s, the sport’s shutterbugs are at the very heart of the story: they’re not just capturing it, but adding to it, fanning the flames, authoring running’s many spinoffs and side quests into the worlds of run clubs, brand wars, racing teams, YouTube influencers and underground events.

Tick, Tick…Running Boom!

What makes a running boom? I’d submit: record-setting finishers for the New York City Marathon; a brand-new world major in Sydney; the proliferation of “unsanctioned” events like Take the Bridge, The Speed Project, backyard ultras; the ascension of fresh brands that engage at the community level (Tracksmith, On and Hoka, to name just a few); Instagram and YouTube influencers who run, but aren’t self-professed runners (e.g., the guy who barnstorms the world chugging Guinness also ran a 2:57:53 marathon in Denmark?!); Strava as perhaps the last great social media platform; and of course, the well-publicized explosion of inclusive run clubs.

Popular media seems infatuated with run clubs as a nouveau dating platform — and sure, some people are meeting significant others at these events — but the broader appeal of run clubs is more practical than romantic. They’re a social outlet, a safety net (running alone can be dangerous, depending on your schedule/neighborhood/gender) and a proven incubator for incremental progress. Some meet three times a week for track workouts and long runs, others meet once a week and sometimes skip the miles for pickleball.

It might feel a little messy to contextualize an entire “moment” in running under the same umbrella. Can we really sort the obsessives who stalk the Trials of Miles homepage and those who ordered their first pair of running shoes during Cyber Week on the same shelf?

I think so. That looseness has always been at the very heart of running. First-timers run the same course as elite marathoners. Runners share roads, tracks, paths. The sport’s moment-to-moment pains are relative, as are an individual’s greatest triumphs. Your mileage will vary (literally), but the point is that running feels the same, up and down the community axis. Besides, as “activity stewards” go, runners have never exactly been gatekeepers. I’d characterize runners’-runners as a breathless, overeager bunch, if anything, with an open-door policy.

Who knows how long it will last, but these days people actually want to walk through that door. The sport is the coolest it’s been in a long time, somehow playing the simultaneous roles of welcoming and rebellious. I was amused the other day, in an age where some online have called running “the new skateboarding,” to learn that some runners are putting their marathon times on their resumes. Why? Running is also associated with commitment. Achievement. Zillennials can’t afford homes, but they can earn marathon medals…and get tagged in great photos along the way.

Every step of the running boom, at every level, has been captured. Running photographers aren’t just showing up to shoot Olympians in Paris; they’re faithfully cataloging sessions with local run clubs on rainy weekday mornings. No corner of the running movement — no single runner — is seen as too insignificant (or let’s just say it: too slow) to feature in the overall construction of the 2020s’ Instagram Running Complex.

These photos have mythologized the sport and demystified it at the exact same time. Even if your algorithm isn’t as running-pilled as mine, it’s relatively easy to stumble into slideshows showcasing the joy and grit of running. Maybe photos of someone you know, or people you’d like to know (especially those who are gnawing on croissants or clinking beers at the end of the slideshow, their miles done and dusted).

It’s impossible to give running photographers total credit for spurring this 360-degree movement. That would discount massive global forces like COVID and Strava. But you’d be a fool not to acknowledge the situation’s chicken-or-egg qualities. Countless nascent runners have likely started running on account of certain photos — and certain running photographers.

Grayson Wise, 28, hails from Ohio but has lived in the Prospect Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn for the last three years. He takes photos for Dirty Bird Run Club, a sprawling, West Side Highway-based crew founded by Jack Gilbert. Wise joined Dirty Bird in March 2022 with the intention of getting into running, even though he’d long “seriously hated” it. Just two weeks into his tenure, he rolled his ankle while playing pick-up basketball.

Wise didn’t want to lose his connection to the club so quickly, though, and asked if he could bike along the club’s route and snap some photos. Gilbert obliged; casual content creation is a familiar story in the world of run clubs. Two years later, Wise’s ankle is back to full strength (he ran the NYC Marathon this year), and he’s at the peak of his photographing powers, capturing outtakes from On events, marathon-finisher portraits, bar-hoppers cheesing during the club’s “Save the Turkey Crawl.”

“I’ve been a photographer for about five years total,” Wise says. “I did it a bit growing up, but really got into photography when I started owning a gym, Rocky Mountain Athletics, out in Denver with my brother. I knew we’d need all sorts of marketing content and figured it was a good time to break the old camera back out, so I got a lot of reps shooting all sorts of fitness content. [In New York] I collaborate with the clubs I run with and have made friends in, so I’m always happy to help out shooting their events, new merch, anything else they need.”

A run club like Dirty Bird doubles as a hungry and hopeful brand. It hosts events with dive bars and yoga studios, pairs with giants like On and upstarts like Cadence (a fledgling electrolyte drink) and vends merchandise like a rock band. The goal that unites all of these projects is adding — and retaining — members. Flying the flag. At their best, running photographers aren’t just marketers. They’re boots-on-the-ground storytellers, distilling the vibes of a given club or event into images and video.

(This typically isn’t a cynical, get-rich-quick enterprise. But as there are a lot of run clubs now, and we live in the age of influencers, outliers like Austin’s controversial Rawdawg Run Club — the cursorial equivalent of a TikTok house — do exist.)

Running is an extremely small community. You can be a crew runner and be one connection away from an Olympian. The spiderweb is super tight.

– Photographer Joe Hale

Dave Hashim is another photographer who’s on the right side of the fence. A 40-year-old from Western Massachusetts who studied film at the University of Michigan, Hashim has worked with brands like Nike, Brooks and Saucony, and got his start with Brooklyn Track Club.

“In 2021 I picked up a camera with the intent to shoot running as just a hobby,” Hashim says. “I was still very new to running and didn’t realize there was an entire culture around the sport or even the activity. Initially, I just wanted to photograph my friends and make them look cool. I had no idea this small hobby would eventually turn into my entire career.”

Hashim launched a website that year called NYCRunPhoto.com, which makes it easier for runners to access photos of themselves from recent events. The shots are free to download and really freaking good. Hashim just requests proper credit in the event that a photo is posted to Instagram…which it usually is. The campaign helped him grow his online portfolio, connecting him to more runners, clubs and brands throughout the community. (And especially the NYC running community, which, as you may have gathered by now, is the nexus of the running photographer revolution.)

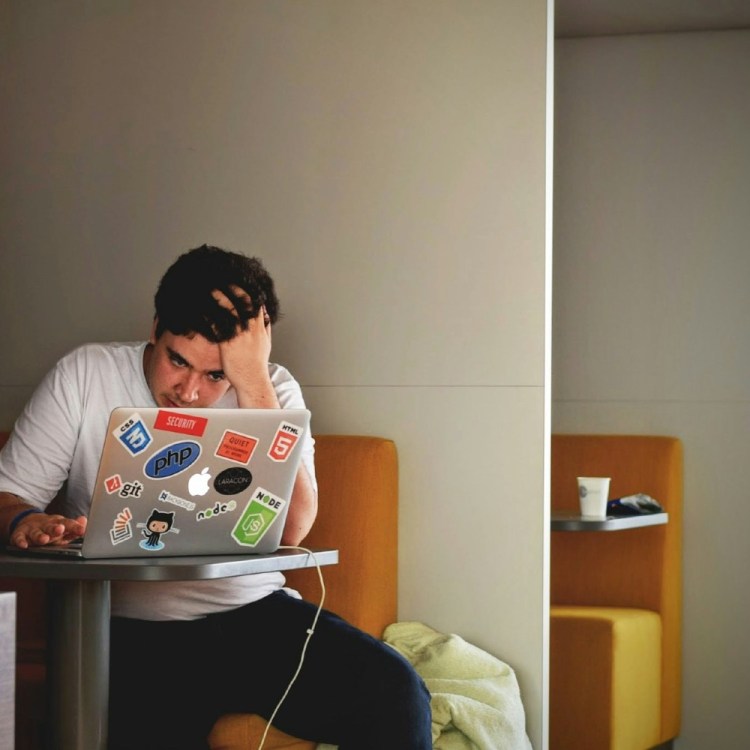

Hashim says he often gets messages from people wondering how they can launch a career as a running photographer. “Honestly, I tell them all the same answer,” he says. “Just start. Go photograph a track practice, or bring a camera to the next race. Go shoot a friend’s workout. You’ll learn a lot…it doesn’t need to be so formal. There are so many opportunities to tell stories of the local runners through images.”

The Art of “Running Photography”

Earlier this December, the nation’s best high school runners descended on Portland, Oregon for Nike Cross Nationals (NXN). It was a muddy affair. The prized recruits raced through a forest of Douglas firs, slipping down the final track as neon-orange Nike pennants fluttered in the wind and the wet. On hand to capture the afternoon were three up-and-coming running photographers: Don Smalls III, Jordina De La Rosa and Robby Zacharias, all of New York City.

I can recall watching NXN as a teenager, following the runners from my region (Northeast) via a stream that looked bootlegged, like I was squinting at a Premier League game with a link from Reddit. I loved the high school running scene then and followed it like a fan — even while the sport’s stars were simply my much-faster peers. It’s fascinating, then, to ponder this moment in the sport: when young fans have access to professional-quality media from the day’s action, and young talent is crossing the country for the meet of their lives…only they’re not competing in it. The trio’s work was supported by veteran photographers Connor Surdi and Nick Carnera.

What if you don’t have a legendary mentor, though? What sort of technical expertise does one need to shoot subjects in constant motion? It’s one thing to put yourself out there — to knock on The Armory’s door until your knuckles hurt, or take that brave first step to take photos at run club — but how does a running photographer make sure their photos don’t suck? That their composition makes people look good? That it has something to say — or, at least, something to say that’s different from every other budding running photographer?

“Photographing running is all about having a fresh perspective,” Hale explains. Even though running belongs to the same family of action photography, “[it] isn’t like basketball or soccer, where there’s an element of unpredictability to it. It’s extremely predictable. People move at usually the same speed, in the same direction the whole time. That means it’s not about differentiating yourself via the action, but rather how you see it. Trying to innovate through aerial perspective, different focal lengths, shutter speeds, lighting setups and post-processing is how to set a running shot apart.”

Hale says he’s taken photos of hundreds of thousands of runners passing by in a “standard” way. “There’s a time and place for that,” he says. “But I really try to shoot by thinking through the facility, course, event or athlete to find differentiating points to set my photos apart.”

This can involve some acrobatics. “I’ve gotten pretty good at Citi Biking one-handed while taking photos,” Wise says. “A lot of times the hard part is just keeping up. I shot a race a few months ago that had runners going right through Downtown Brooklyn. Even on an e-bike I could barely keep up with the leaders, especially weaving through traffic. But that’s also what makes it so fun — you have to be fully engaged the whole time, and you know you only have a split second to capture the shots you see.”

Far from understanding the wizardry of camera operation, I also don’t speak the language of photography. Me words guy. So I don’t exactly know why I like certain running images. I just do.

To lend a hand, Hashim offered some critical context on what makes worthy running photography: “You need to ensure you’re capturing the full context of the scene, photographing the runner in a flattering way (or a specifically unflattering way…running is ugly sometimes) and providing a visually pleasing composition. All while you and the runner are in motion.”

The task combines a variety of photographic disciplines. The photographer must understand their optics (which lens to use when, with respect to available light and desired composition); they should know how to capture a runner in stride (or more generally, how the individual’s running form will translate to the camera); they have to build muscle memory and hand-eye coordination for capturing runners while on the move (from the side of a bike or the window of a car); they need to understand how to work with skin tone, color grading and light in the editing process; and they should feel comfortable shooting bizarro events in low or nonexistent light (as modern runners love meeting for run clubs at dawn and racing half-marathons with midnight start times); and they ought to keep social media in mind, too, as the ratio requirements of a platform like Instagram (4×3 and 9:16) may, from time to time, dictate framing and composition.

It might seem like that list of commandments is missing a crucial entry — “a running photographer should own a very expensive camera” — but Hashim points out that camera equipment has become more affordable in recent years. It’s now possible to acquire a camera with specs like 24-megapixel resolution, 4K video and high-frame-rate shooting for a sum of $1,500….instead of $5,000. Riding a wave of democratization, more running photographers can enter the space. They already have.

Wrangle these forces together, over and over again, and a running photographer begins to cultivate a sense of style. A point of view. Hale says that sometimes, and particularly when shooting for a client, he has to cater to a creative brief. But his favorite gigs are when he can capture whatever is most interesting to him. “My style is energetic,” he says. “Lots of pops of color, motion blur, close-ups.”

Wise, meanwhile, mentions his love of unusual compositions. “I love to get up-close with the subjects, to capture the little moments that highlight the emotions and effort of the runners,” he says. “I also try to pull from as many different references as possible. Whether it’s a skate shoot I saw in an old Thrasher magazine, recreating School of Rock scenes with a running team or highlighting run club members like a ‘choose-your-player’ screen in an old video game…I’m always trying to bring unexpected ideas to my work.”

For his part, Hashim says people tend to gravitate towards his work because of its organic, cinematic quality. “I always want my images to feel authentic and lived in,” he adds. “My goal is always to try to sustain the level of fidelity in my images. I don’t love to just add grain or filters. I want the content and composition of the image to speak for itself.”

Running Photographers Are Runners

Even as running photographers cultivate and retain distinct styles, I’ve noticed some common penchants across the form. Like: purposely blurry images, in-motion portraits where runners acknowledge the camera, glorious backcountry adventure shots, and of course, lots of sweat. That these motifs are widespread isn’t a bad thing — the photos that employ them are usually visually striking. An individual image’s ultimate efficacy (its mix of originality and memorability) is contingent on the talent, vision and execution of the photographer.

Another common through line: community. Think explosions of confetti on marathon day, Champagne showers when a relay team crosses the finish line, Renaissance painting-sized portraits of run clubs once the work is done. These photographers shoot with compassion. They photograph runners like they’re their friends, because they are. They photograph runners as if they themselves are runners, which they usually are. They understand why a face would look like that at this point in the race; they recognize the quotidian joy of chatting with a running partner during a cooldown.

Hashim told me that when he first started running in 2019, he didn’t own any running clothes. After a ton of research, he eventually splurged on a cap from Ciele. He wore the hat for hundreds of miles, including three marathons and some ultras. “Fast-forward to shooting a campaign for them,” he says. “Not only was it an incredible experience, but I felt like I was right where I needed to be in my career and life. When you freelance, there aren’t many times you feel like that.”

Wise has a pinch-me moment, too: when his photography expanded into documentary. His short film, If It Hurts, Good, followed a team from Almost Friday Run Club as they ran The Speed Project, a relay race from Santa Monica Pier to the Las Vegas Strip. Wise was up for the assignment on principle, calling TSP one of the purest forms of running there is, but the project took on a special significance when he learned AFRC was running for their friend and founder, Sam Norton.

“Sam passed away a few months earlier,” Wise says. “He’d been the one to submit an application for this race, and it was accepted a few days after his funeral. The team came together around the idea of running this race in his memory. Spending 40 hours in a van, watching as they fought through 340 miles of bad weather, hurt legs and raw emotions was incredible. I’m so proud of the work I did to capture that experience for them. I love shooting running when it’s not just about the running. [It was] one of the most meaningful experiences of my life.”

Hale doesn’t have trouble getting into The Armory anymore. He’s chopped the wood, carried the water, shot thousands upon thousands of photos. “Running is a vehicle to show off places, people and things,” he says. “And when you dive in, there are so many different perspectives to show within the sport. The elite scene views running so much different than a run club in a city, but at the end of the day it really is just putting one foot in front of the other.”

All booms bust in the end — or at least settle in. However long this running boom lasts, we’ll have endless, resonant proof that it happened. That we were here for it. That this time, when the sport opened its doors, the world came charging on through.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.