“Do you mind if we go to your place instead of mine? My apartment looks like it belongs to a mental patient.”

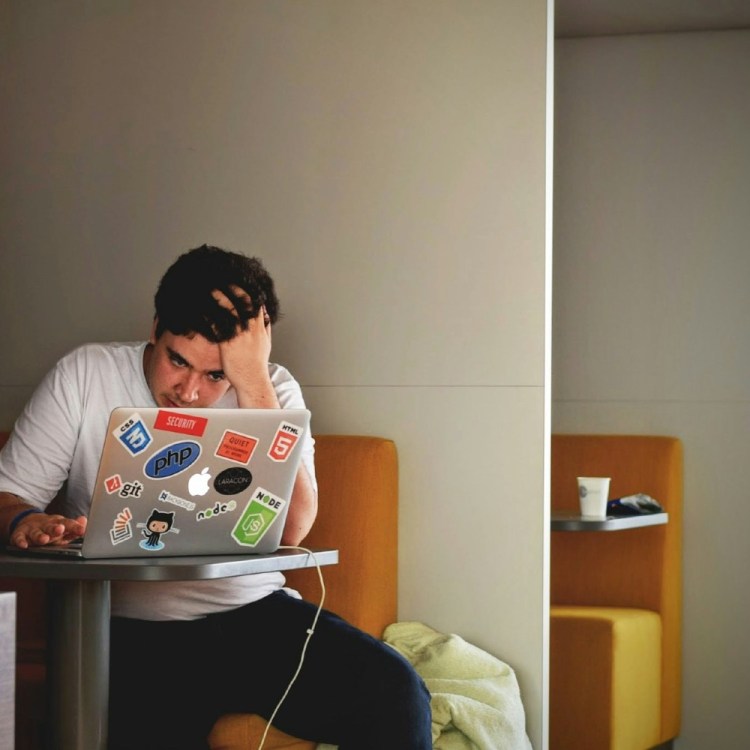

I was kidding — sort of — when I gave that excuse to a friend who was trying to coordinate plans last June. But when those words escaped my mouth, I was surprised by how much they stung. I’ve never been neat, but in the month or so prior, the clutter in my apartment had gradually spiraled out of control, reaching a point where deep down I knew something wasn’t right. Normal people don’t live like this, I’d tell myself. If you walked into someone else’s place and it was this messy, you’d be alarmed.

And yet, I still couldn’t bring myself to clean it up. I knew my apartment was gross, and I very much wanted it not to be — not to be a place I was ashamed to let anyone else see — but whenever I thought about fixing the situation, I felt overwhelmed and paralyzed. I’d let things pile up so badly that I didn’t know where to begin, and starting the job of tidying up felt impossible. Days and weeks would go by where I’d tell myself that I was going to clean and then I simply…wouldn’t. Or couldn’t. Instead, I’d scroll aimlessly on my phone, go to a movie, put on a record or binge-watch whatever the latest cult docuseries happened to be. (I could always take solace in the fact that whatever was going on with me, at least I wasn’t naive or desperate enough to get sucked into a cult.) I had basically transformed into that meme of the cartoon dog calmly sipping his coffee in a room engulfed in flames, except underneath the “This is fine” exterior, I’d silently wonder what the hell was wrong with me.

Around this same time, my lifelong tendency to procrastinate was also getting noticeably worse. I’ve always had a habit of waiting until the night before a deadline to begin writing an article, but it eventually reached a point where I was going to bed and setting alarms to wake up at 3 or 4 a.m. to start writing a story that I’d need to file by 7 a.m. I knew that it wasn’t sustainable, mentally or physically, to be exhausted all the time and living in squalor, so I eventually caved and did something I’ve been putting off for years: I booked the first therapy appointment of my life.

I’d always thought of therapy as something that was hugely beneficial and warranted for others but an unnecessary indulgence for me. There are people out there with real problems, I’d tell myself, people suffering from deep depression or some other form of debilitating mental illness. And I’m gonna go and complain about how my apartment’s a little messy? C’mon.

As it turns out, it’s a good thing I did: After a few weeks of listening to me, my therapist referred me to a psychiatrist, who in turn diagnosed me with ADHD. The symptoms that I’d spent my entire 36 years of life dismissing as laziness or “just the way I am” were actually the result of the chemicals in my brain misfiring. That overwhelming feeling that would hit me whenever I’d think about getting organized? Turns out that’s something called “task paralysis” or “executive dysfunction,” and it’s one of the ways ADHD tends to manifest in women. That extreme procrastination? It’s actually because my brain wasn’t getting enough dopamine — stress gives us a rush of dopamine and adrenaline, so raising the stakes and putting myself under the stress of a looming deadline was my brain’s way of getting a fix. The way that once I finally do start writing, I tend to lock in so hard that I sometimes forget to eat? That’s called “hyperfocus.” My lifelong habit of fidgeting by twirling my hair or picking at my cuticles? Also a known ADHD symptom.

The one that was most surprising to me, however, was weight gain. People who have ADHD are five times more likely to be overweight than people who don’t — because eating also gives us a dopamine hit, because issues with impulse control can mean a lot of snacking, and because executive dysfunction or lack of motivation can keep us on the couch. Like a lot of people, I’d gained a lot of weight during COVID lockdown, but as the rest of the world returned to normal, I found that I couldn’t stop gaining weight. And just like my messy apartment, it felt completely overwhelming, so naturally I did absolutely nothing to address it, letting the pounds pile up until they felt insurmountable.

I’d always thought of therapy as something that was hugely beneficial and warranted for others but an unnecessary indulgence for me.

What I’ve since realized is that I needed to fix my brain before I could fix my body. (To be clear, not all large bodies need “fixing,” and the decision to lose weight wasn’t an aesthetic one. I had reached a point where the extra weight I was carrying was making me physically uncomfortable — getting winded climbing the subway stairs I used to be able to jog up, having more frequent flare-ups of the autoimmune disease I also have — and I was concerned about my health.) Around the same time I started therapy, I started taking Zepbound, a GLP-1 weight-loss drug, which almost immediately quieted the “food noise” in my brain and made it so that I was no longer constantly thinking about my next meal. Since mid-June, I’ve lost about 40 pounds — 10 of which were after a gallstone brought on by rapid weight loss forced me to go off the Zepbound. (I like to joke that I lost weight to get healthy and instead one of my organs grew a rock. Go figure.) I was worried that stopping the drug would cause me to gain all the weight back, but so far I’ve managed to continue to lose, albeit at a slower pace.

That success I attribute to a different drug, the Wellbutrin I started taking for my ADHD. The food noise returned once I went off Zepbound, but the Wellbutrin helps me ignore it. I still catch myself thinking “I wish I had a snack right now” while idly watching TV, but now I’m able to follow that up with “…but I shouldn’t.” I still get the urge to order delivery from a nearby restaurant, but I’ll stop myself and walk over there to pick it up — or sometimes even decide to cook at home instead. I’m less focused on how much I’m eating and more concerned with choosing healthier foods when I do. The Zepbound helped jump-start things physically — you’d be surprised how much easier it is to work out when you’re not carrying a bunch of extra weight, and dropping a big chunk of it in a short amount of time helps create a snowball effect — but treating my ADHD has helped me get motivated to go outside and move my body. The day I really, truly noticed the Wellbutrin working was the Saturday I found myself at home without plans and decided on a whim to go on a four-mile walk. Who am I now?

My psychiatrist once told me that the brain is malleable; it adapts to new environments or behaviors, so the more you eat healthy and start going on walks, the more it reacts by thinking “Oh, I guess we’re someone who eats healthy and goes on walks now” and causes you to stop craving junk food or a sedentary lifestyle. As much as it pains me to admit it, all those platitudes about how getting started is the hardest part and we’re all that stands in our way? Those are true. How annoying.

I’m still a work in progress, but my therapist has helped me see that that’s okay, and that I need to give myself grace and stop looking at everything in absolutes. There’s so much more to life than the simple binaries of messy or immaculate, fat or thin, productive or unproductive, easy or impossible. I’m not going to completely overhaul my life overnight, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t taken great strides this year. The fact that I’m currently writing this article a full 24 hours before it’s due feels like an enormous victory.

So yes, my apartment still probably looks like it belongs to a mental patient. But that’s because it does — and finally admitting it and finding medication that works wonders for me have helped me realize that there’s no shame in that.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.