Before he was the founder and president of Motown Records, Berry Gordy was a high school dropout who’d served in the Korean War and come home to try to find work as a songwriter while managing a store that sold jazz records and 3-D glasses.

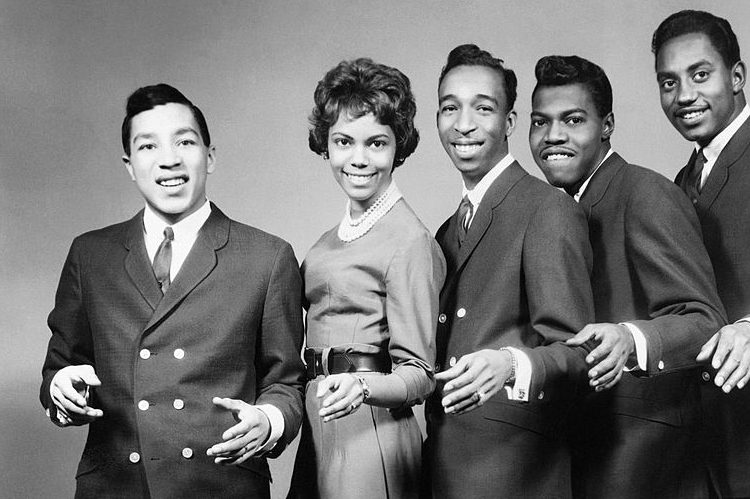

In 1957, the same year singer Jackie Wilson recorded a Gordy tuned called “Reet Petite” that turned into a modest hit, the aspiring songwriter discovered a group called the Miracles which was fronted by a charming young man named Smokey Robinson.

Miracles singer Claudette Robinson, who married Smokey two years later in 1959, was there when Gordy first saw the group perform at the Jackie Wilson studio.

“At that time, Mr. Gordy was a songwriter,” Robinson tells InsideHook. “He had not become the president of Motown or anything because Motown didn’t exist. But at any rate, he was very interested in the songs that we had sung. And he began to work with us.”

Originally signed to Gordy’s first label Tamla Records, the Miracles moved over to Motown once it began operating in 1959 and gave the company its first hit record with 1960’s “Shop Around.”

As she was the first woman to be signed by the label, Gordy dubbed Robinson, who recently released a children’s book called Claudette’s Miraculous Motown Adventure, the “First Lady of Motown.”

Though the title didn’t come with any official duties, Robinson and the rest of her groupmates took their roles as Motown’s first stars seriously.

“I’ve always given the very best that I could, in terms of Motown and our being there first,” she says. “We had an opportunity to get out on the road and really be with other artists that were not Motown artists. When “Shop Around” became a million-seller, that’s when things kind took off. Other artists started to coming to Motown to see if they could do the same thing. Of course, some of them did. And that was a good thing. It was a competition, but in a good way. It was a competition that made you want to work harder, and then to encourage all the other artists that were coming in.”

Being the first group on Motown also meant The Miracles had to blaze a touring trail for other acts on the label to follow so they hit the road when the label was in its infancy for a string of shows in the South.

“Traveling through the South, with a lot of the racial prejudice that existed, there were some road experiences that were wonderful and some that weren’t so wonderful,” Robinson says.

When The Miracles initially hit the road, there were six of them in a car — the five members of the group and their guitarist.

“That was a lot of people in a car,” Robinson says. “We were traveling all over the country. Back and forth. New York to Florida and all the places in between. Sometimes we got paid and sometimes we didn’t. Sometimes we’d be trying to talk to the sheriff of the town to see if we could get our money. And the guy would be everything: he’d be the sheriff, the judge, the manager of the place that we were playing, he would be everything. So of course, he’s not going to go against himself and we had to leave. Most of the time, it was okay. But there were times that we came with nothing and we left with nothing.”

And, given the attitude of that region at the time, sometimes there were other issues that had nothing to do with money.

“As far as our talent and performance, we were never received in an unfriendly manner,” Robinson says. “We were always received well for our work. But there were other situations that were not great.. Sometimes we would want to get gas for the car and when they saw we were black, they might not let us get gas. Or if we wanted to go to a restaurant, not even to sit down, but just to have something to take out like some sandwiches, they may not allow that either. As far as restrooms, those were labeled white or colored because black hadn’t come into play just yet. I always tell people I’ve lived long enough to be all of the above. I’ve been colored, I’ve been negro, I’ve been black, I’ve been African-American, and then I think we went to black again, and then we came back to African-American. So I’ve lived in all those eras.”

It wasn’t in the South, but Robinson also remembers a particular occasion in the group’s early days when they encountered difficulties after they were booked to play at The Apollo Theater in Harlem with Ray Charles’ group backing them as the house band.

Thanks to an issue with their sheet music — not having any — The Miracles almost didn’t make it onto the stage.

“We were rehearsing and when we got ready for our turn, the problem was we just had chord sheets,” Robinson says. “We didn’t have full arrangements and these are professional musicians. They’re like, ‘What is this? What?’ So actually Mr. Charles heard what was going on and, because this was his band, he called Smokey. He told him to sit down and sing whatever you all are trying to sing. Then he had someone come with a pen and paper and he wrote, what I call, our first professional arrangement. Had it not been for him, they probably would have sent us home because the band was not going to play for us.”

Robinson ended up touring with the group until 1965 when, after having had several miscarriages, her then-husband and Gordy convinced her the continuous traveling was bad for her health.

Now, more than five decades after she got off the road, the First Lady of Motown still looks back with fondness on the label that gave her such an illustrious title.

“One of the reasons I feel Motown is important is that it has brought people together,” she says. “Music is always important. It has no color lines or financial basis or anything. It’s just something that can be enjoyed. You can talk about many, many, many, record labels, but the one record label that has fortunately continued to stand out is Motown. Many people think it was the studio, it was Detroit. But what many did not know is that all those recordings were not done in Studio A [in Detroit}. Some were done in New York, some were done in Chicago. It had something to do with the sound. The sound of the people coming together that was making that particular record and that sound. It wasn’t necessarily just Detroit.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.