Journalist Peter Ames Carlin has written about some of the biggest names in rock music: his bibliography includes works about the likes of Bruce Springsteen and Paul McCartney. In many ways, the subject of his new book, The Name of This Band is R.E.M., fits seamlessly into his areas of interest. R.E.M. have sold millions of records, have a place in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and continue to find listeners among younger generations today.

But R.E.M. also took a different track than most to get there. They have a longtime association with Athens, Georgia, for instance; they’ve also eschewed a high-profile reunion tour (so far, anyway) despite having stability that few other bands of their stature can claim. Carlin’s book is an empathic, insightful look at this band and its long history — and it does an excellent job of explaining how R.E.M. went from cult band to stadium act without changing much along the way.

InsideHook spoke with Carlin about his own connections to R.E.M.’s music, the moment from their discography that surprised him the most, and the odds of whether Bill Berry, Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Michael Stipe might reunite in the years to come.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

InsideHook: Late in the book you talk about the different types of R.E.M. fans, from people who are dedicated to their debut, Murmur, to fans who got into them after they signed to Warner Bros. Where do you fit on that continuum? What first drew you to their music?

Peter Ames Carlin: I was probably a little bit of a later adopter. I came in right around the mid-’80s. Obviously I was aware of them from the beginning when they first began to pop up every so often on MTV. And of course I was reading about them in Rolling Stone. I was very aware of who they were and what they were, but it wasn’t until they began to pop up on mainstream radio. I grew up in a part of the country where there wasn’t a lot of left of the dial taking place. I grew up in Seattle and then I was in Portland for a lot of that time. That alternative culture thing hadn’t really taken root yet, certainly not in the media.

Once “The One I Love” was on the radio, all that kind of stuff, it began to resonate a little more. The point at which I really tuned in in an intense way was that moment from the late ’80s and into the early ‘nineties ’90s when their music and their vision became so tied into that breeze of idealism and political progressiveness that was just beginning to take root. There was something about not just their music but how they went about creating it, and also how they chose to run their career and run their business, staying in Athens, really leading with that sense of social and political responsibility that I found moving.

As they began to connect more with the culture and became much more present, that part of their story became that much more vivid. And then, of course, their incredible run of really, really big records made such a big impact on everyone. They became so prevalent in mainstream media.

I talk a bit in the book about the Murmurers, the people that caught it from the get-go. Obviously I admire that and, to an extent, I’m envious of the people who managed to pick up on the signal that early. I was in the Pacific Northwest, so we were a long way away from their stomping grounds and it was more challenging to find them. But I know what it’s like to get into an artist of any sort, musicians and writers who seem to be speaking to you directly. There is something so powerful and moving about that experience, and it’s jarring when you see your guys, your heroes, who you feel like are speaking to you directly, begin to connect with the broader world and suddenly you find yourself surrounded by fellow fans and travelers who don’t feel familiar to you and maybe who you don’t even like. But I was never too much of an artiste to ever feel that about R.E.M. I was just glad to be there with them.

Was there something specific that prompted you to start working on an in-depth look at R.E.M.’s music in the 2020s?

Their music is always around; they were too popular for too long for it to fade, but it wasn’t as prevalent in the mainstream. Even though their influence was all over the place, as a result of their being who they were — which is to say not obsessed with fame and maintaining their reputation — it began to slip away a little bit.

I also felt like that message of idealism that they were so symbolic of, that that had faded away too — that commercialism and cynicism of mainstream media had swelled to a degree. And I missed them. I missed what they represented and how they lived their lives, and I wanted to dive back into that.

I spent a lot of the first Trump years writing about Warner Brothers Records and how they came from being a very counterculture type of outfit and using those values in a weird way. They became one of the most popular, successful and influential major labels in history, while still being sweet and cool people. I saw R.E.M., who ended up becoming Warner Brothers artists, as a continuation of the same story.

I seem to remember one of the members of R.E.M. saying in an interview when their second greatest hits album came out that they had to be talked into it by U2. It also seems telling that they haven’t gone that route and done, say, a reunion at the Sphere in Las Vegas, even though the members are all alive and seem to get along.

I think the first words of the book are “Even from the start, you would know them from their refusals.” The litany of things that were just traditional rock star music industry things to do, they wanted no part of. Over the years, those evolved a little bit as they grew and changed and came to understand that some of the lines they drew weren’t necessary in order to maintain their artistic vision.

Probably today somebody is sending them an enormous offer to re-form and play a few shows or play some festivals and stuff. It’s generational money that they could theoretically get. A lot of artists take that on, because why not? I don’t think it’s always necessarily a purely financially driven, cynical move. Yes, it’s financially remunerative to get the band back together and hit the road. But you know what else it is, I think, is super fun and satisfying. Because if you were part of a group of people who made a lot of successful art, that’s a really cool feeling, you know? And probably you love those other guys to some degree.

The one thing about an R.E.M. reunion — which probably won’t happen, but who knows, maybe it will — is that I think the thing that might tip them over to do it, should they ever do it, isn’t just the fact that they would all make a ton of money, which they definitely would. And maybe that will become something that’s appealing to them. But I think it’s also because they really enjoy one another as people. They care about each other. They love each other. They really brought out the best in each other. They really enhanced each other’s work.

See/Hear: The Best Movies, TV and Music for December 2024

This month, we’re gifted a Bob Dylan biopic, a new “Squid Game” season and moreIn the acknowledgements, you wrote that the members of R.E.M. didn’t talk to you for this book. Did that mean you did more archival research than you’d initially planned? Was there anyone who became more important to the finished book than you would have expected?

I’ve written a bunch of these books and sometimes I’ve had cooperation and sometimes I haven’t had cooperation. Sometimes people do whatever they can to try to stop you. R.E.M. were far more cooperative and friendly throughout. It may have been because I know Peter Buck because I lived in Portland for a long time and he was one of my neighbors for the last 10 or 12 years I was there.

So Peter knew my work and we would see each other around town and occasionally get together. I started talking to him about this when it was an abstract idea. He was very forthright and said that he doubted that they would cooperate, but he also said that he didn’t have a problem with this. I also know Bertis Downs, their manager, who’s been a friend of mine for more than 20 years now.

I spoke to Bertis and he basically said, “Sure, send me a letter. We’ll talk it over and see what they think.” The answer I got back was a little disappointing. Obviously it would have been great to have them and be able to talk stuff through with them. But on the other hand, I’ve met them all. I know some more than others, and Peter by far the best. He was very helpful, but all of them were, along the lines of telling their friends, “Yeah, go ahead, talk to him, he seems like a good guy.”

I did a ton of original new interviews. I always read everything I can get out of the archival stuff and just try to put it together to create the fullest possible portrait. One of the interesting things is, because R.E.M. have always been very community-based, there were a lot of people with a lot of interesting stories to tell.

Anytime something like this happens and a bunch of guys get together and create a band and work really, really hard to become successful, there are always going to be people left behind. There are always going to be people who felt hard done by these guys that made it big. So, of course there were people who had stories to tell that were less happy than others. That’s just an inevitable part of life, and you need to add that part of the context as well.

Whenever I write a book like this, the challenge is to try to get as close as you can to the essence of the art and understand the artists who made it and how they made it and why they made it without necessarily violating the zone of privacy that all humans deserve.

One of the compelling things about R.E.M., and one of the reasons why I wanted to write about them, was the fact that they had been so good at maintaining that distinction between who they were as artists, what mattered to them as artists, and how they made their art without really disemboweling themselves for the entertainment and intrigue of the media and people that read that stuff.

So, the fact that they didn’t want to do that with me was disappointing, but also strangely affirming because it confirmed what I thought I had figured out about them as people and the level of emotional maturity and sophistication that they took into their project. They all came from really good families, so they were well-raised, which sounds kind of snobby. I don’t mean it to sound that way, but they were fortunate in that they didn’t come with the kind of dysfunction and darkness that inspires a lot of art in people. They certainly all had their challenges and issues to work through, as we all do, and a lot of that surfaces in the art as well, but they managed to create art and work through that stuff without shredding the veil of privacy that most well-adjusted people try to keep around themselves.

One detail I loved in there was when Michael Stipe’s father figured out that Bill Berry had contracted Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

His dad had been in the military forever and knew all about these different kinds of diseases. In the same way that Mike Mills’s dad was a fairly successful singer on a more regional scale. He took a great deal of pleasure in performing and did, I think, throughout his life. When Mike joined the band — a lot of times when your kid joins a band and drops out of school, it’s a nightmare, and parents get very upset about that. Except not Mike’s dad, because for him, his son was living his dream. I think having that type of background really allowed them to function as sensible, grounded people as they were diving headlong into this very surreal and at times destructive part of the world where you’re being turned into a product.

Original R.E.M. Lineup Appears Onstage for First Time in 17 Years at R.E.M. Tribute Show

Specifically, Michael Shannon and Jason Narducy’s “Murmur” tour stop in Athens, GeorgiaI don’t think I had realized the full story behind how they fell out with Jefferson Holt, which I think I remember reading about as it happened, but which also seems like it would have been a much bigger deal if it had happened in an era with social media.

I approached it extremely carefully. These guys had been very, very close. Jefferson was essentially the fifth member of the band and was treated as such. He was a big part of their progressive vision because of his family. His mother was a very influential, very politically progressive state representative in North Carolina. She and her husband raised Jefferson and his siblings as very socially aware, politically progressive, sensitive people.

Jefferson’s imprint runs deep in the DNA of that band. There’s no two ways about it. But one of the things that happened when a band begins and they’re very young, in their early 20s — and Jefferson wasn’t much older than them — was that they really turned to him to help figure out what their group identity and vision was going to be.

He really helped form that. He helped set up that office and keep it in Athens and set an example for how to be a socially responsible organization and a socially responsible big business. So it was extremely disappointing to them when it turned out that he had this Achilles heel of these relationships that he was having or wanting to have with people in the office. I think for a lot of people, it’s difficult to figure out where the line is, especially if you’re in a relationship where you’re the powerful person and you’re interested in someone who works for you and is less powerful than you. You have to be extremely delicate about that. And this was a long time ago. As little as our society has evolved since then, it has evolved to a degree, and it was evolving then.

The allegations were that Jefferson had not evolved with them and had created some uncomfortable situations. I think the intensity of their discomfort may have had something to do with the fact that they were rock-and-roll guys who had been on the road at that point for 15 years and that they too had developed a lot of friendships with people, let’s put it that way. And some of them were more fleeting than others.

That’s young people on the road in alternative cultures, living alternative lifestyles. I think the fear of possibly being lumped in with that or the allegation being that those guys did exactly the same thing was terrifying. Also, I think they wanted to protect the people that worked for them.

I think also, in a lot of these types of relationships where somebody like Pete Best, the Beatles’ first drummer, gets kicked out, to me, it’s never the one thing. The one thing that they end up getting fired for is just like the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back because there’s a whole array of other things. You know, Jefferson was to some extent losing interest in their project. He was more comfortable as an outsider being kind of a rebel in pop music than he was at being at the top of the heap in pop music, which is where they were.

He had less to do because they were older. They were in their early and mid-30s by then and didn’t need a counselor helping to guide them. They could guide themselves. There were all those things. I think there was some unhappiness about the ticket pricing for the 1995 tour that he was involved with. There were allegations that they had been profiteering because their tickets cost were what now seems like an unbelievably small amount, like $40 or $50.

It really was a different time, wasn’t it?

It’s super delicate. I talked to Jefferson. I bumped into him at a show when I was in Athens in 2022, but he was forbidden from saying anything on the record. The way things were written, he couldn’t really speak to me off the record, either. There was a point where I just needed him to confirm some details about his family and his mother; just biographical Jefferson Holt facts. He was very, very leery about cooperating even on that level. But that goes to show you how bitter and unresolved that conflict is. To me, that’s the saddest part of their story.

Was there anything that really surprised you when you were revisiting these albums? Were there any songs that felt like overlooked gems where you might not have had that realization if you hadn’t embarked on this project?

I had never really listened to their set at Glastonbury in 1999 during the Up tour, which was the first major project they did after Bill Berry left, where they had to reinvent themselves as a trio. There was that very famous performance in 1998 at the fundraiser for Tibet in Washington, D.C., and they came out and debuted a lot of their new songs, which were very electronic and very different from what they had done, and didn’t work out well. Everyone was super eager to hear their new music, and they came out and there was a lot of atmospheric bleeping and whirring. It wasn’t as melodic, and in a big stadium full of people, then they’d break into “Losing My Religion” or something, and the place would explode.

They were still trying to figure themselves out, but a year later when they got to Glastonbury and they had everything to prove again, and they have this enormous audience — 100,000 people or whatever — they came out and they just rocked. I mean, they blew the place away. It was a huge success.

One of the things that I thought was so cool was that for a band that at that point had been together for nearly 20 years, and had just released an album that had not connected with listeners in the U.S., they came out and they blew the doors off the place playing mostly new stuff, hardly any of the classics from the 1980s and just a handful of things from the first half of the 1990s.

In the first 30 or 45 minutes of the show, they had played maybe two of their hits, and the live versions of the songs from Up now had the guitars forward. They were great R.E.M. songs, like “Walk Unafraid” and “The Apologist.” They’re dark and weird, but still somehow full of hooks, and so fun to listen to, so satisfying and meaningful. Twenty years in, they were still at the top of their game.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.

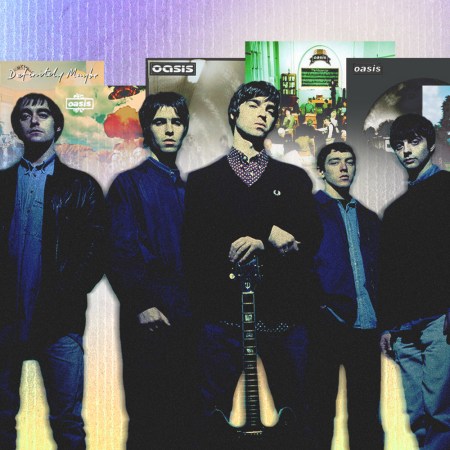

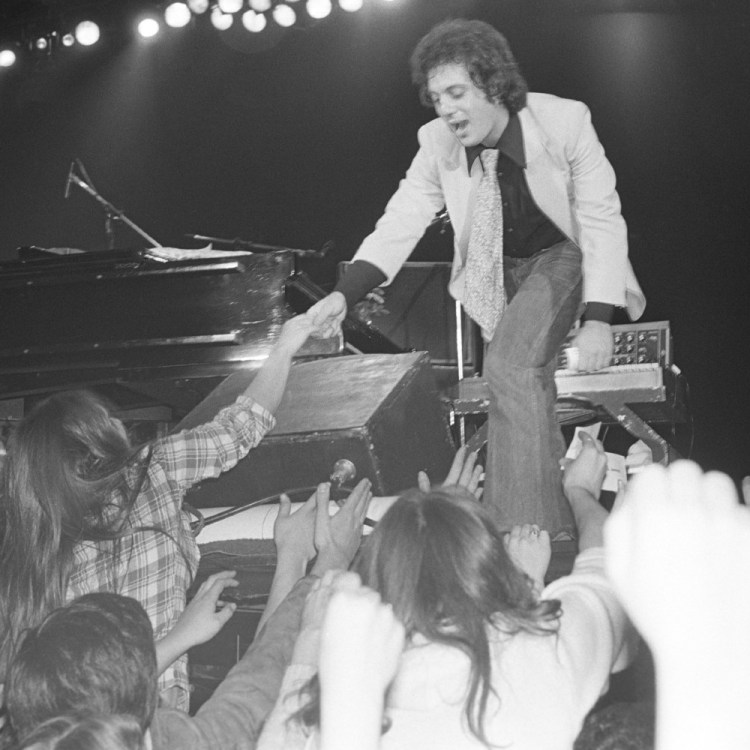

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?fit=1200%2C800)