If great songwriters live long enough, eventually they’ll offer their take on what they imagine heaven is like. In 2011, when Paul Simon was about to turn 70, he released “The Afterlife,” an amusing vision of the great beyond in which a newly deceased man learns that getting through the Pearly Gates is akin to going to the DMV — “You got to fill out a form first / And then you wait in the line” — and that his pickup lines aren’t so hot — “I said ‘Hey, what’cha say / It’s a glorious day / By the way, how long you been dead?’”

Off his acclaimed record So Beautiful or So What, “The Afterlife” is one of Simon’s best latter-day songs — clever, colloquial and instantly catchy — but it’s the ending that really clinches it. After getting the hang of heaven, our narrator offers an uncommonly appealing view of the hereafter:

After you climb up the ladder of time

The Lord God is near

Face-to-face in the vastness of space

Your words disappear

And you feel like you’re swimming in an ocean of love

And the current is strong

But all that remains when you try to explain

Is a fragment of song

Lord, is it Be Bop a Lula? Or ooh Papa Doo?

Lord, Be Bop a Lula? Or ooh Papa Doo?

For Simon, heaven is a song — the mysteries of the universe as inexplicable as a perfect melody, of which he has written many.

Earlier this year when the 83-year-old icon announced “A Quiet Celebration,” a new tour tied to his latest album, 2023’s Seven Psalms, it was a surprise on several fronts. He had already embarked on what was billed as a farewell tour in 2018; in addition, during the rollout of Seven Psalms, Simon revealed he had lost significant hearing in his left ear, which made the possibility of future performances seem unlikely. Plus, there was the matter of Seven Psalms itself, an introspective, atmospheric suite of tunes — almost a series of movements — that lacked the traditional pop structure of his best-known material. This somber, idiosyncratic record — which came about from feverish, middle-of-the-night writing sessions — didn’t seem ideal for launching a tour, especially one that would feature the full 33-minute album, in its entirety, at the start of every show.

There were other reasons to be concerned about “A Quiet Celebration,” which began in April and is set to conclude in early August. Simon’s voice has lost much of its expressive power in recent years, his hearing loss appears to be permanent, and in the midst of this tour, he canceled a few dates in order to receive surgery to relieve “chronic and intense back pain.” For a staunch perfectionist, the inevitable decaying of the body has undoubtedly been a humbling, illuminating experience. But for fans aging along with Simon, “A Quiet Celebration” provides an opportunity to measure their own journey. It’s hard not to view these shows as a way of saying goodbye — and for him to say goodbye to us.

Not surprisingly for a musician who doesn’t do anything without applying the utmost of care, the current tour deftly caters to its star’s current limitations. Taking center stage with a small speaker perched close to his right ear, Simon has been performing in intimate, indoor spaces that emphasize pristine acoustics. Here in Los Angeles, where I saw him for the third of five shows, he chose the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is used primarily for classical music concerts. As if to prove to naysayers that this wasn’t going to be a cash-grab greatest-hits tour, he consciously shied away from playing several of his biggest smashes on Saturday night. Sure, “Graceland,” “Homeward Bound,” “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” and other past favorites found their way into the set. But before those chestnuts, he wanted audiences to meet him where he is now and share in the anxieties he faces today.

“The Afterlife” may cheekily envision what comes after this world, but it’s hardly the first time Simon has contemplated mortality. He wasn’t yet 34 when he wrote the ironic “Have a Good Time” about being bummed about another birthday. Getting close to 60, he penned “Old,” which reminded listeners that no matter how old we feel, at least God is still older than us. Speaking of the Almighty, He’s made various cameos in Simon’s work, frequently portrayed as an unknowable scamp whose grand plan is frustratingly baffling to us mere mortals.

But with the exception of “The Afterlife,” lately the playfulness of Simon’s musings on dying and the existence of a higher power has receded, replaced by a sober desire to understand if there is a God and, if so, what will happen when Simon meets Him. That unease suffuses Seven Psalms — so much so that its seven songs eschew conventional hooks. In a career of left turns, the album may just rank as his boldest.

[Simon’s] worn voice and the graceful arrangements ensured that each [song] was flecked with urgency, treated like final proclamations.

To be sure, Simon has taken myriad creative risks since he went solo in the early 1970s. But where previous experiments sought to expand his palette within the strictures of conventional musical genres — say, embracing South African mbaqanga on Graceland or toying with samples on So Beautiful or So What — Seven Psalms is a rejection of those conventions.

Appropriate for its sleep-deprived origins, the album’s winding, immersive tunes feel like snippets of dream logic backed by music full of strings, acoustic guitars, flutes and other non-electric instruments. The songs resemble prayers, the words an apprehensive gathering of regrets and things left unsaid. Simon’s voice is hushed, its usual sweetness sometimes strained, and the tracks’ meditations can sometimes lead to mush. (“Inside the digital mind / A homeless soul ponders the code” is a notable clunker.) But Seven Psalms challenges you in ways Simon’s agreeably approachable work rarely does, his preternatural gift for effortless melody set against a musical style that’s not necessarily his forte. No one confuses Seven Psalms for Metal Machine Music, but it’s as close as Simon has ever come to the avant-garde.

At the sold-out Disney Hall show I attended, only two weeks after that surprise surgery, Simon came out to a standing ovation before explaining we’d be hearing Seven Psalms first. There was nothing apologetic or self-effacing about his announcement, and likewise he and his band’s performance was confidently delivered, bringing out the subtle shadings of a record I don’t love but grow more impressed and moved by with each exposure. On the album, Simon’s aged voice suitably fits these last testaments — his lyrics wavering between worry and acceptance for all that he cannot control — but the intensity of feeling was even more palpable on stage.

Backing musicians that sometimes numbered around 10 wove through the airy, reflective compositions, with cellos, flutes and chimes adding not just color but vitality to an album that very much feels like a steeling for the end of something. Still, Simon’s vulnerable voice and plaintive guitar held the delicate compositions together. On songs such as “Your Forgiveness” and the album closer “Wait,” Simon senses his days drawing short, measuring just how little time he has left. But defiance and anger are in short supply — instead, the prevailing mood is one of gratitude, a sentiment amplified by the presence of his wife Edie Brickell, to whom he’s been married since the early 1990s.

Indeed, it’s her guest vocals on Seven Psalms’ final songs, “The Sacred Harp” and “Wait,” which personify Simon’s guess in “The Afterlife” that in heaven “you feel like you’re swimming in an ocean of love.” On stage, it wasn’t just her lilting, twirling voice but the way she and her husband looked at one another that suggested the abiding affection of a flesh-and-blood love affair that grows more precious the older they get.

Whereas in his early solo career Simon lamented the volatility of romantic relationships, his recent songs have found him trying to maximize the days he still has with his beloved. From You’re the One’s devastatingly matter-of-fact “Darling Lorraine,” where a tempestuous marriage only finds resolution in a literal death-do-we-part, to So Beautiful or So What’s calm paeans to a love that has lasted, Simon knows how good he has it. At Disney Hall, Brickell’s glowing vocals were almost too much to bear, a sign of devotion as she helped lift up her frailer, clearly appreciative partner.

After completing Seven Psalms’ funereal grandeur, Simon and his band took a brief intermission before returning for an attempted buoyant take on his live staple “Graceland.” Unfortunately, Simon’s voice couldn’t hold up its end of the bargain, its fragility dragging down the song’s wistful look at a disillusioned single father on a road trip to Memphis with his son. The stilted performance seemed to augur a discouraging rest of the evening in which Simon would try (and fail) to reach past heights, serving as a sad reminder of how we physically fall apart though our spirits remain vibrant.

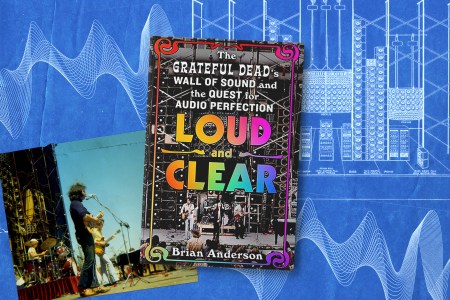

How the Grateful Dead Created the Accidental Future of Sound

“Loud and Clear” by Brian Anderson argues that the band’s most ambitious experiments weren’t musical or culturalThankfully, Simon found his groove after that rough start, settling into a series of sturdy mid-tempo songs that were enlivened by the chamber-piece setting. A bluesy “Slip Slidin’ Away” gave way to a majestic “Train in the Distance,” one of his many sharp, sad portraits of bad love that is heightened by the eternal riddle of its chorus: “Everybody loves the sound of a train in the distance / Everybody thinks it’s true.” Picking three songs from 1983’s Hearts and Bones and two from 1990’s The Rhythm of the Saints, the less-celebrated albums that came before and after Graceland (which only featured twice in the show), Simon wasn’t relying on crowd-pleasers. Some of those set-list decisions might have been informed by his hearing and vocal issues — the danceable “You Can Call Me Al” or “Late in the Evening” probably would have been labored — but it might also be that he was looking toward thematic connections that transcended his obvious smashes.

One of those themes was the inexorable passage of time and the privilege of being alive long enough to witness the seasons of a life. Simon played two songs written for specific children: 1973’s “St. Judy’s Comet” for his first son Harper and 2002’s “Father and Daughter” for his only daughter Lulu, who was in the audience. After each of those songs, a photo of the proud dad with his little kid was displayed above him on a screen, a running bit of reminiscences throughout the show. Earlier, we saw images of the three “Johnny Aces” — Johnny Ace, John F. Kennedy and John Lennon — who are memorialized in “The Late Great Johnny Ace,” his stunning ballad about gun violence and people taken too soon. Before launching into the evening’s other Graceland number, “Under African Skies,” Simon noted he’d written it for Ladysmith Black Mambazo leader Joseph Shabalala, who died in 2020. (A picture of the two of them also flashed on the screen.) Later, Simon saluted bassist Bakithi Kumalo, the last surviving member of the Graceland band to still be out touring with him.

Simon’s discography has always been filled with melancholy observations, but the evening felt especially haunted by friendly ghosts, juxtaposed with happy images of his children and the occasional presence of Brickell, who popped up a few times during the hits section, including gleefully whistling the hook to Simon’s deathless “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard,” a song that might as well be about eternal youth.

On songs such as “Your Forgiveness” and the album closer “Wait,” Simon senses his days drawing short, measuring just how little time he has left. But defiance and anger are in short supply — instead, the prevailing mood is one of gratitude.

Not one of the songs performed during the show’s second half outstripped its recorded version. If you’ve been going to Paul Simon concerts throughout your life — my first was the “Born at the Right Time” tour of the early 1990s — you’ll have heard several of them plenty of times. But his worn voice and the graceful arrangements ensured that each was flecked with urgency, treated like final proclamations from a man who, in some cases, had written the songs decades earlier.

Which is my way of saying that, nearly 35 years after I first heard it live, I was moved anew by The Rhythm of the Saints’ “The Cool, Cool River,” a rumbling groove about the undefeatable anger and sorrow that courses through society. If the song has always suffered a bit from being too conceptual, when Simon plays it on stage, then and now, its momentousness becomes overwhelming, the rhythmic undertow ultimately ceding to a guarded hopefulness. Its key stanza is even harder now to believe than it was 35 years ago, yet he still sings it, the grain in his voice making it all the more moving:

I believe in the future

We shall suffer no more

Maybe not in my lifetime

But in yours, I feel sure

“The Cool, Cool River” was never a hit, but Simon’s insistence on playing it felt meaningful. In a song in which he calls prayers “the memory of God,” Simon was already pondering what gets left behind after we shuffle off this mortal coil. When he first made his name, with Simon & Garfunkel, his hits were generational anthems — songs in which he talked to people his own age about the world they were inheriting — and some of those put in an appearance at Disney Hall. But as epochal as show-closers “The Boxer” and “The Sound of Silence” remain, their youthful vim doesn’t cut as deeply as his examinations of parenthood, grownup love and adult compromise that would fuel his richer, subsequent solo career. On stage, the Simon & Garfunkel songs marked a bygone moment of fleeting optimism for a generation determined to change the country — that generation’s failure made all the more poignant by the older man now singing them, the distance between then and now so pointed.

I’m 50, and I was far from the oldest person in the audience. Many of the concertgoers around me had probably been with Simon since the beginning. His unresolved feelings about death, disappointment and legacy are their feelings. It was tempting to approach “A Quiet Celebration” as an opportunity to say goodbye to Simon — even more so since Seven Psalms comes across as an earnest endeavoring to put one’s existential affairs in order before it’s too late. (Tellingly, some of the album’s finest moments come during the final movement, when Brickell sings reassuringly, “Life is a meteor / Lеt your eyes roam / Heavеn is beautiful / It’s almost like home.”)

But if Seven Psalms is meant to be a vision of the end, the rest of the show — weathered, emotional, invigorating — felt like the afterlife. He didn’t perform “The Afterlife,” but perhaps that would have been too obvious. Simon believes heaven is a song. Maybe we’re already all living there.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.