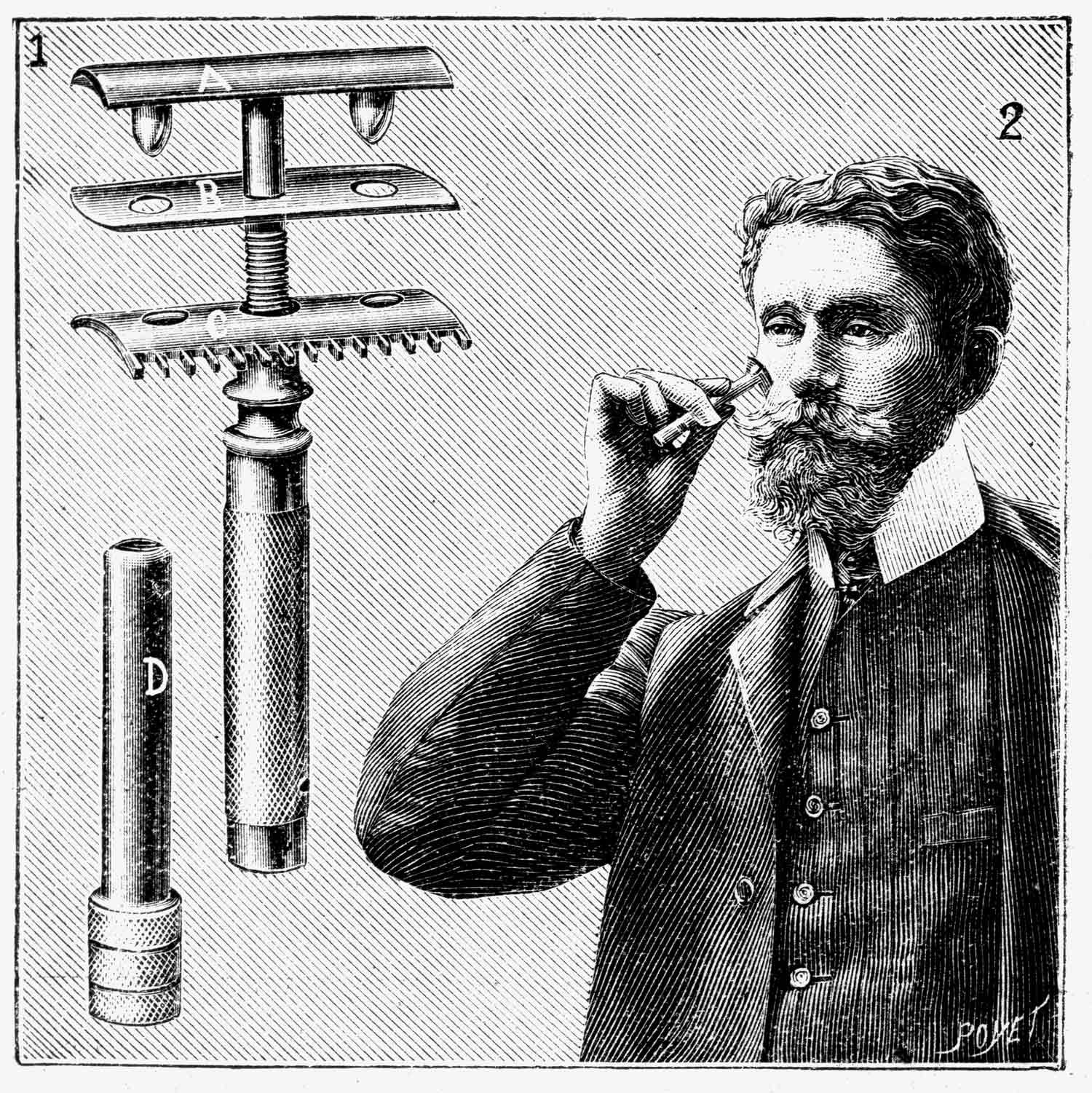

While your average second-century Roman would be dumbstruck by your car or your smartphone, there is one piece of daily gear he would likely fail to be impressed by: your razor. For all of the industry’s vaunted technological advances, a sharp bit of metal is precisely what he might use to tame his whiskers, too. Surely by the 21st century, we should be shaving with lasers, he might propose, had he any idea what a laser was.

Laser shaving is an idea that’s been considered since the 1970s, first dismissed for the obvious safety challenges, and, a decade ago, proposed again, this time using the light traveling along an optical fiber to do the cutting. It’s still just a concept, great for the next Star Trek movie perhaps. All the 21st century seems to have offered in the shaving department is, well, more sharp bits of metal stacked on top of one another.

“Yet the business of razors has always embraced ideas of the new,” says Alun Withey, Ph.D., a historian specializing in facial hair and senior lecturer at the University of Exeter. “Go back to the 1750s and the language used to promote them isn’t that dissimilar to the language used now. It’s all about the ‘shininess,’ the ‘hardness’ and ‘crispness’ of the blade. There’s always been that appeal to the masculine love of tools and technology — it’s why even disposable razor blades are made of titanium and make claims to use nano-tech now, even as the base technology itself has really remained much the same for many decades.”

“Nothing truly radical has come along,” he admits. Instead, the shaving industry has proven to be a gold mine for those studying the effects of pizzazz as much as product.

“The marketing of the shaving industry stands on a tripod of ideas — closeness of shave, convenience and cost — which exist in a kind of unstable equilibrium,” argues a happily-bearded James Fisher, Ph.D., professor of marketing at Saint Louis University. “Consumers are inevitably not really buying into new technology, but just a smooth face or an easy shave or a satisfying daily ritual. In other words, what makes a shaving product different is that it has a story to sell, something the consumer can relate to, and maybe stay loyal to for life. The trick is to keep that consumer engaged, with the occasional new packaging or new design, with the promise of technological advance.”

“I don’t think we can get that much closer with a shave. In fact, we probably reached ‘peak shave’ some time ago.”

Alun Withey, senior lecturer at the University of Exeter

Fisher cites an article on the spoof news website The Onion, in which the apparent CEO of Gillette explains why the answer to a competitor introducing a four-bladed razor is “Fuck everything, we’re doing five blades.” “It just so perfectly captures the product improvement escalator characteristic of the shaving industry, one that’s subject to diminishing returns,” Fisher says. “If you only have four blades and your competitor has five, then, ipso facto, yours is inferior. The great enemy [of the industry] is when all products are perceived as being more or less the same.”

Therein lies the problem. The two-blade razor, it’s often argued, did introduce a genuine benefit: the first blade lifted the hair, the second cut it closer. But that doesn’t mean that endless blades lead to an ever-closer shave — or, at least, as Withey points out, not one that’s perceptibly different to the human hand or eye, especially at seven in the morning.

“I don’t think we can get that much closer with a shave,” he says. “In fact, we probably reached ‘peak shave’ some time ago.”

While the shaving industry loves its trademarked lingo — the likes of ProGlide, Xtreme, LifeProof, Hydro, SkinGuard, FlexBall, and now EasyRinse, the “anti-clogging” system launched last year by BIC, with 21 patents and patents-pending involved — Fisher argues that most major innovations in the market in recent years haven’t been technological.

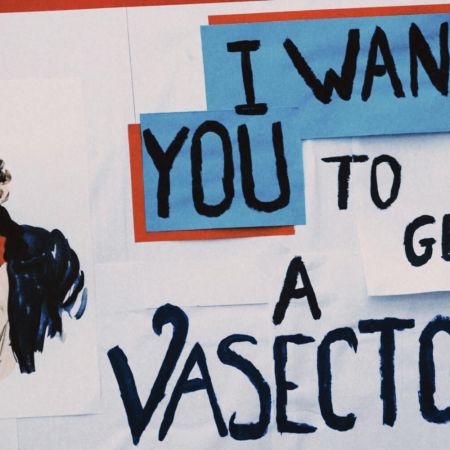

The innovations have instead been ones of distribution, like the price-conscious and more competitive subscription models of brands like Harry’s or Dollar Shave Club; or of attitude, like an emphasis on social issues, recyclability or an ironic undercutting of the machismo with which a lot of razor advertising has traditionally been suffused; or of aesthetic, like the trend towards a more “artisanal” barbershop-style of less technology, not more. One of the challenges facing the industry is the elephant in the room: If more tech leads to a better shave, why do barbers still use single straight-edged razors of a kind definitely familiar to our Roman friend?

“The industry is full of gimmicks that I don’t think everyone is buying into anymore,” argues Austin Mutti-Mewse, the creative director of British shaving business Truefitt & Hill, established in 1805 — making it the world’s oldest of its kind— with North American stores in Chicago and Toronto. (He’s currently developing a range of shaving products for King Charles III’s Highgrove brand.) Ask a barber and, Mutti-Mewse insists, they will tell you that with a multi-bladed cartridge product, all you’re doing is taking off more and more layers of skin, to the detriment of your face. A single blade means less friction, and so less burn.

“You just need one blade, a good brush to lift the follicles and a shaving cream, not a gel,” he says. “And practice to master the technique.”

That last point is important. “Single-blade razors provide for a close shave when in experienced hands,” stresses Dr. Camila Janniger, clinical professor of dermatology at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. “With the multi-razor blades, and especially poor-quality ones, it’s exceedingly easy to go below the skin [because the action of multiple blades causes it to bulge up slightly], causing damage to hair follicles that can lead to inflammation and ingrown hairs.”

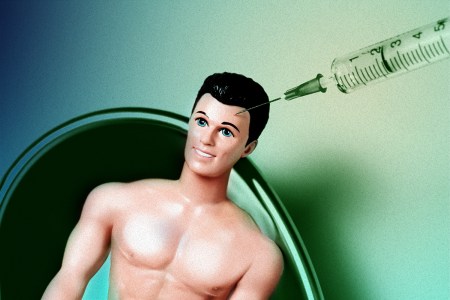

More Men Are Getting Botox. Should You?

The cosmetic procedure has been growing among men for years. Here’s what to know before going under the needle.Is the market for many blades just a means of compensating for a lack of shaving skill, then? After all, protecting delicate, often sensitive human skin while also slicing through human facial hair with the same strength as copper wire is no easy balancing act. And if men were once taught to shave by their fathers, societal pressures no longer expect them to be clean-shaven. At least one generation has grown up with stubble and beards as the norm. When they do shave, a device that’s more idiot-proof may be the order of the day.

So while there may be room for an even closer shave, it’s other aspects of the razor that companies increasingly focus on, mostly aimed at making shaving less arduous, like swiveling heads (introduced in 1970s), lubricating strips (in the 1980s) and, more recently, vibrating the razor’s edge to reduce friction. Greater blade longevity might be an objective too: In 2020, metallurgists at MIT worked out why even hair could, over time, chip away at a razor’s edge — it’s to do with the mixed composition of the steel — and subsequently “filed a provisional patent on a process to manipulate steel into a more homogenous form, in order to make longer-lasting, more chip-resistant blades.”

Of course, ease of use is also a large part of the appeal of the electric shaver — dry, fast, fuss-free, blood-free. “The fact is that there’s not much difference in closeness between an electric shaver and a razor shave at home now, and the difference in closeness between shavers is hard to spot [for users too],” concedes Christopher Barleycorn, U.K. marketing manager for Wahl, a company probably best known for its barbershop tools. “That means innovation in other aspects of the shaver [are pushed to the fore]: comfort, ease of cleaning, multi-functionality and so on. How a shaver feels in the hand matters, even the color.”

Yet if a wet-shave razor is limited by cost, weight, dimensions, function and other factors, electric shavers have more room to play with new technological ideas. With all the hype around how artificial intelligence will transform everything, inevitably AI now ponders your chin, too. Inside products like the Philips Norelco Series 9000 — a nod to HAL 9000, perhaps? — are all the normal bits: sharp pieces of metal that do the cutting, a flexible head, coating to reduce friction; but the app-connected gizmo also touts itself as “the world’s most intelligent shaver powered by AI,” with built-in motion-control sensors to track and guide your shave’s pressure, speed and action in real time. If your father didn’t teach you how to shave better, the app will.

“I think people are getting tired of [the constant upgrading], the version 10 and later the version 20 [of what looks to be the same thing]. The category can be overwhelming. They’re asking, ‘Well, how much more of a close shave can I really get?’” says Dana Medema, senior vice president of personal health North America at Philips. “But I don’t think the market is really about that now. The holy grail is a product that’s adaptable, [that recognizes] that every person’s face and skin is different. How do you make a product ‘smart’?”

“The market does need something truly disruptive to come along — for an Apple of shaving to make an iPhone of shaving products, because right now we’re stuck with bloody Nokias.”

Will King, founder of the brand King of Shaves

That’s not the only question the shaving industry is currently grappling with. “How do we meet the needs of both the kind of consumer who wants one tool to do everything, and the one who wants several tools each to do one thing really well?” asks Medema. “How do we address the fact that [the industry] is speaking to four distinct generations now, with four distinct shaving needs? Or that men are grooming body hair too, or that there’s a fluidity in hair norms?”

Given these challenges, it may well prove that the future of shaving technology will be in devices rather than in wet-shave razors — the latter will just start to look increasingly similar. Besides, if electric-shaver technology leaves more gaps for startups to potentially revolutionize shaving, Will King — who, 30 years ago, founded the King of Shaves brand — argues that the wet-shave cartridge-razor market is virtually unassailable.

Together, Edgewell (owner of Schick and Wilkinson Sword) and Gillette command around 80% of the wet-shave razor market. Then, he says, consider that the profit margin on a basic cartridge razor blade is huge — costing just a few cents per unit to make and selling for at least a couple of dollars.

That means that there is the money to invest in R&D that may lead to the development of some new ideas, but also, crucially, money to invest heavily in promotion. As Wahl’s product director Jeff Bovee points out, “[We have] tried to educate men about the gentler shave they can get by switching to an electric shaver, [but] with powerful brands investing so much on the marketing of wet blades it can be difficult to get the message out through all the noise.”

All that spare money only facilitates legal challenges to rival patents from startups, or the outright purchase of the startups themselves. Unilever bought Dollar Shave Club for $1 billion eight years ago, and Edgewell tried to buy Harry’s for $1.37 billion before the deal was blocked by the Federal Trade Commission in 2020 as anticompetitive. When your margins are that big, “Why disrupt a cash-flow hypersonic missile [with bold innovation]?” asks a skeptical King.

Not that doing the new is easy. In 2014, the minnow King of Shaves went up against the giants with its Hyperglide system, which, thanks to a cartridge that produced its own lubricant on activation with water, meant no foams or gels were required. Unfortunately, the project was plagued with manufacturing issues and, ultimately, King sold the tech.

“Nobody has really done anything truly innovative for years, and now the market is more about packaging,” King laments. “Arguably, wet-shaving tech reached its peak with Gillette’s Mach3 [launched in 1998]. That’s just a beautifully engineered bit of kit. Could Gillette develop a laser-powered razor? Yes, I think so. The question is what’s its incentive to do so, when it’s easier and very profitable to stick with, so to speak, an internal combustion engine razor? But the market does need something truly disruptive to come along — for an Apple of shaving to make an iPhone of shaving products, because right now we’re stuck with bloody Nokias.”

King imagines a time when both razor and shaver are replaced by a chemical solution, some kind of smooth on/wash off substance that gently eviscerates facial hair without damaging the skin. But he concedes that this is likely some time away. Oddly enough, even that futuristic-sounding idea isn’t exactly new. Those Romans also used depilatory creams and rubbed them off with some pumice stone.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.