Bruce Springsteen fans who buy a ticket to the new biopic Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere based on the trailers may be in for a surprise. 20th Century Studios has cut together invigorating ads featuring Jeremy Allen White credibly impersonating the Boss, including some sweaty rock-concert footage of him rocking out with an imitation E Street Band. The movie doesn’t waste much time forking over that scene. After an opening childhood flashback, it’s more or less how the storyline begins, with a glimpse of Springsteen finishing up an exhausting tour following his double album The River, which has just yielded his first Top 10 hit.

This concert footage is not the last time Movie Springsteen rocks out, but Deliver Me From Nowhere also doesn’t provide the cathartic elation of A Complete Unknown, the Fox-released Bob Dylan biopic that this one is clearly meant to evoke. Movies like A Complete Unknown have prepared plenty of music fans for the idea of a biography that looks at a crucial section of its subject’s life, rather than doing the full cradle-to-the-grave treatment, and the Dylan picture is a good comparison point for this one — just not necessarily for the most marketable reasons. A Complete Unknown traced Dylan’s path from New York City newcomer to folk sensation to that mythic Going Electric moment. Deliver Me From Nowhere more or less reverses the trajectory: It begins with Springsteen as a rock star reaching a new level of popularity, and follows his artistic decision to resist capitalizing on the success of “Hungry Heart.” Instead, he goes back to New Jersey, reckons with his past, home-records a bunch of hushed, soul-baring story songs and spends much of the back half of the movie haranguing various studio guys about how to preserve the spare, echo-y quality of what they all assumed were just skeletal demos. He makes some attempts to record the songs with a full band, but they aren’t hitting quite right, so Springsteen keeps pushing to scale things all the way back to his home tapes. Yes, despite Springsteen’s arena-sized presence, this is a movie about the making of 1982’s folky, desolate Nebraska, sure to set the hungry hearts of Springsteen’s music-nerdiest fans aflutter.

That material, the stuff that digs (however briefly) into the nitty-gritty of making Nebraska and then making sure it didn’t get gussied up into something bigger, is the best stuff in Scott Cooper’s film. The material about Springsteen’s family and personal life has its moments, but his inner turmoil is too frequently (over) stated, which isn’t really a problem with the material about record-making, where the audience needs more guidance. (The movie seems to think they need it at every step.) Most interesting, if likely familiar to devotees, is that the creation of Nebraska entwines with the making of Born in the U.S.A., the smash 1984 record that followed it and appended “super” to Springsteen’s star. Disney/Fox must have breathed a sigh of relief when they realized they could at least get a scene where Springsteen rehearses the title track in the studio, and indeed, it’s nearly as fun as watching Dylan try out “Like a Rolling Stone” in the earlier film. A Complete Unknown was content to blend Dylan’s rapid succession of mid-’60s classics together in a blur of legendary song-making. If that one was surprisingly hit-heavy for the iconoclastic Dylan, Deliver Me From Nowhere is surprisingly album-oriented for the more traditionally rousing Springsteen.

If the Springsteen movie feels a little incomplete, a little thin in its supporting cast, maybe that’s because it requires a supplementary text: the not-quite-soundtrack accompanying its release. To complete the picture or possibly render it even more confusing, the movie’s opening coincides with an expansive reissue of Nebraska that includes the original album; B-sides, demos and outtakes, some of which feature early versions of Born in the U.S.A. tracks; a live full-album performance of more recent vintage, because he didn’t tour the record back in 1982; and a version of the legendary “Electric Nebraska” that Springsteen long insisted doesn’t exist.

It’s that last bit that will get a lot of fans’ engines revving, even if Springsteen wasn’t completely wrong to deny its existence. The electric version of Nebraska isn’t strictly a full-band run-through of the 1982 album. It lasts eight tracks instead of 10, with “Downbound Train” and the title track from Born in the U.S.A. in place of “Highway Patrolman,” “State Trooper,” “Used Cars” and “My Father’s House.” For that matter, some of the “electric” versions aren’t exactly full-band rave-ups. “Mansion on the Hill” changes the least with the addition of keyboards. “Reason to Believe” gallops a little more with the addition of drums, but it never really blasts off, by design.

“Johnny 99,” though, sounds more like the old-time rock and roll that inspired Springsteen, and that he plays for fun at the Stone Pony in the movie. The original Nebraska version cleverly riffs on that style by hollowing it out, but it’s still a kick to hear a version with prominent drums and keys. “Atlantic City” is such a terrific song that it shines regardless of instrumentation, but some of the electric novelty is drained from how often it’s been played and covered over the years. (The Hold Steady basically released this version of the song already.)

Maybe the most interesting aspect of the plugged-in Nebraska is hearing some of the songs juxtaposed with early versions of those Born in the U.S.A. tracks, following up on the movie’s connection between the two albums — and functioning as an assurance of sorts that Born in the U.S.A. isn’t being forced into the movie to entice more casual fans or, worse, tease a sequel in the Folk Rock Cinematic Universe. (Would it culminate in one of Dylan and Springsteen’s odd, occasional on-stage intersections?) The comparison enhances both records, bringing out the story-song poignance of the big hit’s anthems as well as the classic-rock roots of the artier, quieter album.

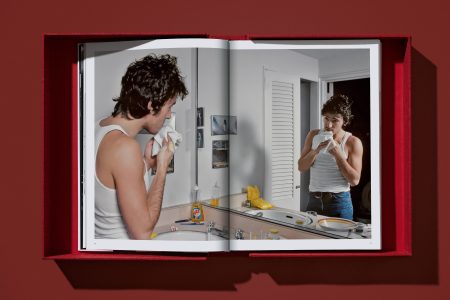

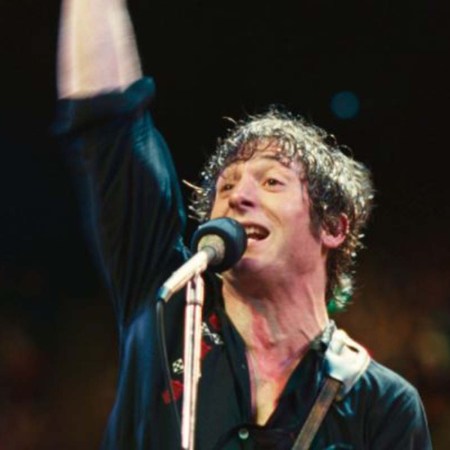

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith Reflects on Bruce Springsteen’s “Darkness on the Edge of Town” Era

Goldsmith’s new photo book captures The Boss at a pivotal moment in his careerIn his 33 ⅓ book on Born in the U.S.A, Geoffrey Himes even makes the hot-take case that despite the record’s reputation as a slicker, more polished Springsteen effort, that it also represents an artistic and lyrical breakthrough for The Boss. To Himes, it’s a culmination of both his increasingly pared down lyrics that strain less obviously for poetry and a greater sense of melody: “The songs on Born in the U.S.A. boast lyrics nearly as good as those on Darkness at the Edge of Town and Nebraska and offer music that is much, much stronger.” He writes extensively about the process of paring down the enormous number of songs Springsteen wrote in the early ’80s, arguing that he should have released even more of it, re-arranging the tunes into three or four albums instead of two. (Many of the other songs from this period didn’t resurface until much later, on various collections — robbing them, Himes argues, of their immediate cultural context.)

Though Deliver Me From Nowhere re-entwines the 1982 and 1984 albums, it doesn’t really offer a sense of the songs pouring out of Springsteen — or even much of that 1980s context that Himes prizes, focusing instead on Springsteen’s haunted past. The filmmakers clearly don’t want to get too far into the weeds on that music-making process, drilling further into the emotional heart of the situation as they see it. That’s probably the “correct” decision, dramatically speaking, even if it doesn’t actually pay off in this particular film. It’s also a reminder that while it can be fun to poke around in an artist’s biography, looking for the stories behind the songs, many of those artists have done an awful lot of work telling the story through the songs themselves.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=450%2C450)

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=750%2C500)