This is the first installment of the 2024 edition of the French Dispatches, our on-the-ground coverage of the Cannes Film Festival.

“Do you have it in you to make it epic?”

So asks Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) of Furiosa (Anya Taylor-Joy) at a pivotal moment in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, which just premiered here at Cannes; it’s been the question on everybody’s mind here on the Riviera, about George Miller’s film and in general.

When Miller showed Mad Max: Fury Road at Cannes in 2015, in the same Night Two gala slot that Furiosa just premiered in, the crowd at the Grand Théâtre Lumière thrilled to what was quickly, and correctly, hailed as, frame for frame and shot for shot, one of the most astonishing feats in modern moviemaking, a high-BPM smashup choreographed in the sands of Namibia for a small army of souped-up rigs, an achievement made all the more impressive by the 20-year odyssey to secure a green light and a shoot plagued by high-risk logistics and turbocharged egos. With Furiosa, the challenge for Miller is to top himself, to make it epic anew.

One fascinating thing about the Mad Max films until now is that they all feel quite distinct from one another. Miller pursues somewhat different aims at a wildly different scale in each film: Max Mad, in 1979, was a skeletal rape-revenge programmer born out of Australia’s rugged exploitation scene; 1981’s The Road Warrior was a post-apocalyptic Rio Bravo with hints of fetish wear creeping into the costume design; by 1985, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome was a comparatively high-concept adventure at the height of Hollywood’s blockbuster decade, made zeitgeisty and campy thanks to Mel Gibson’s waxing stardom and Tina Turner’s supporting turn; decades later, Fury Road pivoted to a female point-of-view, aggressive color-grading, and large-scale practical effects and elaborate mythology conceived in answer to the digital franchise era. Though similarly art-directed and featuring a uniformly frantic performance style, the films change appearance as Miller takes advantage of progressively more resources to do more expansive and baroque world-building; they’re practically standalones, successive variations on a theme, featuring only one recurrent character (though the same actor plays a different key supporting role in both Road Warrior and Beyond Thunderdome).

Furiosa is the first Mad Max to really feel like a sequel; it picks up where Fury Road left off stylistically, and fits snugly, occasionally winkingly, into series continuity. Characters from Fury Road reappear, the look of the movie is painted in the same bold strokes of desert red, sky blue and motor-oil black, there’s the same chase-movie structure and the same avenging-angelic feminism. And the cars look the same.

None of this is precisely a complaint: the film teems with details — wild supporting character names (“Scrotus,” “Rictus,” “The Octoboss,” “The Bullet Farmer”), characters covered in scars, motorcycle helmets made of two skulls padlocked together. Miller is operating at a very high level, and the centerpiece action sequence, assembled from 197 shots staged over the production’s 156 location days, an attack on a convey traveling down a seemingly endless straight road (a Mad Max franchise standby) has a few new wrinkles, including whirlybird flying machines, paragliders and an unconventional fluid used as radiator coolant.

As Furiosa, Taylor-Joy steps into Charlize’s combat boots with a regal and feral take on the role; Furiosa, kidnapped by Dementus’s marauders as a child, is bold, protective, damaged, and has the core strength to hold herself upright under a careening gas truck. It’s an alpha-female role whose demands are first of all physical (a recurrent interest, it seems, of twentysomething actresses hyperconscious of their agency, or lack thereof, in Hollywood; Sydney Sweeney is in Cannes this year to pitch a biopic of the boxer Christy Martin). But just as Mad Max was not the point of Mad Max: Fury Road, Furiosa is not the point of Furiosa.

Post-apocalypse films often give glancing impressions of confusion and collapse, hinting at a larger social order that may be forming in the wasteland but is remote to the characters, their instincts and their traumas — and Mad Max is an archetypal lone survivor type. But Miller is quite interested in how societies form, how resources are allocated, how leaders seize and maintain power.

Mad Max films have evolved from following the group dynamics of roving wolfpacks blindly following their leader, to the bread-and-circuses and frontier justice of Thunderdome, to the citadel of Immortan Joe and his army of War Boys in Fury Road and Furiosa. Dementus at the start of this new film lives nomadically, in a tent encampment, and travels by chariot, but he’s immediately impressed and inspired by Joe’s empire, with its far-flung provinces where metal is mined and oil refined. Resources — water, oil, scrap metal — are always key in the Mad Max films. How are they extracted and allocated; how do leaders maintain power over the men necessary for such a large-scale project? Loyalty in these films is maintained by heralds and hypemen, like the minion declaring the arrival of “The Ayatollah of Rock and Rolla” in Road Warrior, or Fury Road’s fan-favorite Doof Warrior; in Furiosa, Dementus retains a court-fool figure who gestures in a kind of sign language alongside his leader’s pronouncements. They build a legend and inspire devotion — even all those silly character names are like Homeric epithets, which build a legend, and maybe even a belief system. Miller — who puts hundreds of extras through their places in punishingly remote locations — is naturally curious about how self-interested people born into a vacuum can be persuaded to sacrifice for a nation-building process, out of awe of a charismatic leader, or perhaps out of the simple thrill of doing violence. Civilization, or something like it, coheres over the course of the Mad Max films through brute force as in less enlightened times; it’s through this context, in which rulers maintain harems as a symbol of power and a source of new blood bonds, and accept offerings of child brides for the sake of alliances, that Furiosa’s female fury takes on a fairly primal weight.

So, what else will make it epic? (Aside, that is, from tomorrow’s Furiosa press conference, which promises to follow the bread crumbs expertly laid out by Taylor-Joy, who alluded to unspecified difficulties on the shoot in a Times piece written by Kyle Buchanan, author of a book on the making of Fury Road.) In its programming, Cannes strives for a high concentration of big swings landing on flat-footed audiences; early word is notably hyped for films by the French newcomer Coralie Fargeat, whose The Substance arrives on a wave of vague but visceral body-horror hype similar to that that preceded Titane in 2021; for Mohammad Rasoulof, who may attend the premiere of his Seed of the Sacred Fig after fleeing Iran following a jail sentence motivated by the film’s dissident politics; and for late-period, grief-stricken works by David Cronenberg, whose The Shrouds promises to respond to the death of his wife, and Paul Schrader, whose Oh, Canada responds to the death of his friend and author of the film’s source novel Russell Banks, as well as to his wife’s dementia and his own ill-health.

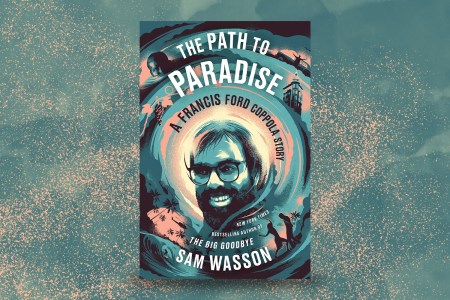

But no swing is bigger than Megalopolis, which screens on Thursday night. Francis Ford Coppola returns to the Croisette, where the grand folly of Apocalypse Now was vindicated with a Palme d’Or, with what promises to be an even grander folly, a self-funded dream project 40 years in the making, already being heralded as a colossal act of either vanity or vision in pieces like an exquisitely bet-hedging Guardian preview replete with anonymous reports of artistic hubris and logistical nightmares. I can’t wait.

Coppola — along with Kevin Costner, here with the first part of his Horizon: An American Saga, premiering out of competition — is part of an inevitably strong American strand at Cannes. Following Jodie Foster in 2021, Forest Whitaker and Tom Cruise in 2022, Michael Douglas and Harrison Ford in 2023, this year will see an Honorary Palme d’Or awarded to Coppola’s buddy George Lucas, late in the festival, to go along with the one given to Meryl Streep at Tuesday’s opening ceremony, following an effusive tribute by Juliette Binoche (who emoted directly to Streep while reading from a printed script she held in her hand; when not distracted by a notably bored Louis Garrel in the audience, the cameras broadcasting the event occasionally picked up snippets of her next line in emphatically underlined 72-point font).

This New Book Revisits Francis Ford Coppola’s Complex Artistic Vision

Sam Wasson on writing “The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story”This was after multiple tributes to Palme d’Or jury president Greta Gerwig: first a clip montage tracing her arc from actress to auteur (eliding entirely the first several years of her career in the so-called mumblecore indie movement, where she did exert significant and formative influence as a cowriter and codirector), and then an exquisitely awkward tribute to Frances Ha’s “Modern Love” dance scene, featuring a French performer in stocking feet singing the song to a very confused audience including, in an aisle seat around the seventh row, the newly Pulitzer-anointed New Yorker film critic Justin Chang, who kept an admirably straight face — better him than me (this is the first time I have ever said this about a fellow film critic enjoying a deserved professional honor).

Per the first tribute montage, which posited Barbie as the fulfillment of a muse and model’s larger creative aspirations, Gerwig’s Barbie, like Furiosa — and like Streep, who, said a choked-up La Binoche, “changed the way we look at women” — is a strong female character; since the festival resumed service after the canceled 2020 edition, two of the three Palmes d’Or have gone to female directors, tripling the pre-pandemic number of “just Jane Campion,” and Gerwig is the first female jury president since Cate Blanchett in 2018.

In that Times piece, Taylor-Joy called herself “a really strong advocate of female rage,” and perhaps the rage that Furiosa embodies will be the most epic thing at Cannes in 2024. Following last year’s Depp-bacle, Cannes will acknowledge #moiassui with a short film by Judith Godrèche, the actress who has done much in the past year to lead the advance of Me Too in France by calling out multiple prominent directors; the thought here is that she apparently has bullets still in the chamber, with the whisper network getting so loud that Cannes president Iris Knoblach has already been asked straight-out what will happen if a filmmaker in the official selection is named and shamed during the festival.

Perhaps protesting too much, the opening night film, The Second Act, from Quentin Dupieux, revels in un-PC dialogue couched in have-it-both-ways self-parody; in a sign of things to come, a character’s transphobic rant is met with a pained reply that you have to watch what you say these days. (The actor delivering the warning is Louis Garrel, whose father Philippe Garrel, a director whose work I treasure, has been accused of sexual harassment by numerous actresses in a pattern of behavior spanning much of his career.)

Dupieux, a prolific and prankish filmmaker who loves cheap rural locations, often outdoors, presumably because they’re cheaper to set up, often writes his way out of corners with meta-jokes that point out the artifice of filmmaking; The Second Act plays out across multiple layers of reality and fiction, with a cast of French luminaries also including Léa Seydoux and 2022 jury president Vincent Lindon portraying actors who frequently break character to bitch about the script, their castmates, or the state of the industry and the world. Complaints about cancel culture dog the set of this meta-movie, along with various global crises, the decline in theatrical moviegoing and artificial intelligence, all of which leave the characters equally embittered and disillusioned about the future of filmmaking — all are, in Dupieux’s intermittently funny dark comedy film, equivalent reasons that artists can’t say anything anymore. It’s a sour, defensive film, and as I walked out of Debussy the clouds over the Mediterranean opened up and it started raining, as if the sky was weeping for cinema.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.