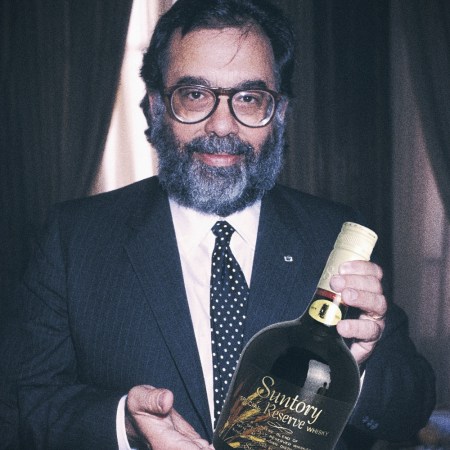

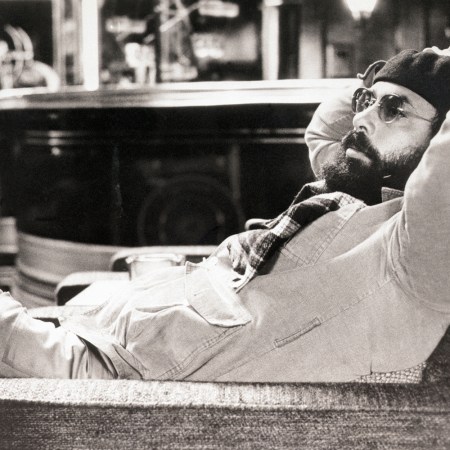

It can be dizzying to consider the career of Francis Ford Coppola, part of a generation of filmmakers who changed the face of American movies forever — and yet for whom filmmaking is only one fraction of his overall story. Coppola’s business ventures include his production company American Zoetrope, a successful winery, a literary magazine and a 2018 foray into cannabis.

Sam Wasson’s new book The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story explores the contradictory impulses, artistic vision and constant evolution of Francis Ford Coppola. Focusing largely on the productions of Apocalypse Now and One From the Heart, Wasson creates a portrait of one man’s vast artistic ambition— one that (to this reader, anyway) portrays Coppola as a kind of precursor to the tech moguls who would take San Francisco as their base of operations decades after Coppola did so.

It’s an insightful book that takes stock of Coppola’s importance to film history and creates a vibrant portrait of a restless artist constantly on the move. InsideHook spoke with Wasson about the process behind this new book and how the subject compared to some of his other forays into cinematic history.

InsideHook: Was The Path to Paradise already underway when you began speaking with Coppola, or did it come out of conversations with him and grow into something organically out of that?

Sam Wasson: It’s been a book that’s been underway in my mind for about seven or so years. When I first started talking about doing it seriously, Francis was reluctant to be a part of it for many years. At one point, thinking that I didn’t want to do it without him, I abandoned the project because I felt I shouldn’t go forward without Francis. But then it didn’t leave my mind, and I knew I wasn’t going to walk away from this and that I had to do it, Francis or not. And so I forged ahead respectfully, but in the course of it, I re-engaged with Francis and I had been recommended to him by that point. So he knew I was okay, and then we were up and running.

How is he as a conversationalist? Was that experience different from some of the other filmmakers and writers you’ve spoken with?

Yes. He is highly informed and highly discursive. It almost seems when he’s talking to you, you could say he rarely stays on subject — or you could say his definition of the subject is so vast that one thing is also another thing. And so talking to him, you really have the sense of the size of his learning and contemplation. He’s like a library, and not just a film [library], of knowledge. He’s a bigger reader than most any other filmmaker I’ve ever met by far. And his tastes are totally diverse — fiction, science, history, you name it, really. I think you can see that influence in his movies, oftentimes to their detriment, oftentimes not. But his interests extend beyond movies. Movies become for Francis a way for him to engage in all of these other things.

As you point out in the book, one of the really fascinating things about Coppola is he doesn’t necessarily have as distinctive of a filmmaking style as some of his peers. Do you think some of that is because of the fact that the Godfather films, while they are landmarks in American filmmaking, are also something of an outlier in terms of his career?

Yeah, definitely. That’s one of the reasons. Also, he’s more collaborative than most filmmakers, so he’s going to be influenced by what’s going on around him. That’s another reason why his style seems to be changing. Also, he himself changes — and this is one of the big themes of the book. The material that he picks is, from film to film, so different. And he wants a style to come out of that. So that’s another reason.

Also, he’s not a natural, and he himself recognizes this. He wasn’t born thinking about movies the way Polanski or Spielberg or Scorsese were, whose styles are innate. Francis is interested in theater, literature, all of these things. So as a latecomer to the movies, he really sees himself as more of an explorer. It’s like he hasn’t arrived yet at who he is or why he’s making movies.

Do you think that’s something common to his collaborators as well? I’m guessing you’re familiar with the Lawrence Weschler book on Walter Murch’s forays into astrophysics. [Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists -ed.]

I’ve heard of it. I’ve never read it. How is that?

It’s good! I’m a fan of Weschler’s stuff in general, and I’m a fan of Walter Murch’s work, so I might be the ideal reader for it. I was thinking about that as I read your book because they’re frequent cinematic collaborators whose work goes far beyond film. One of them is an editor who’s also worked in astrophysics, and Coppola is someone who became a successful winemaker and published a successful literary magazine.

You’re absolutely right. It’s a perfect comparison, and you’ve also characterized what the Zoetrope ideal is with your description of Murch, definitely. And Storaro is also one of those guys. Dean Tavelaris is also one of those guys. These are not people who live and breathe movies to the exclusion of all else, and there’s no judgment in that. Some may even say that’s an advantage, but yes, you’re right. These are polymaths and adventurers of the mind.

Did you also find comparisons between what Coppola was doing in the period around Apocalypse Now and One from the Heart and what some tech moguls were doing decades later in San Francisco? It seems like there are parallels there in terms of trying everything and sometimes succeeding and sometimes not in a way that never occurred to me before reading this.

I don’t know a lot about the tech business and the tech renaissance, except to know that it was a renaissance. And what all of those renaissances have in common, and I base this on my knowledge of Zoetrope and my knowledge of the beginnings of the movie business, is that there is an incredible amount of improvisation, and that means trial and error. There has to be a freedom to fail, and Coppola allows that.

I mean, again, you could say that freedom to fail even to his own detriment. I happen to think it’s freedom to fail for his own success. But both of those renaissances have that in common. People have to be free, and the only way for them to be free is for them to know it’s okay if they crash and burn.

Your book focuses on the period from Apocalypse Now to One From the Heart as the spine of the book, and you move forward and backwards in time from there. Did you always have that in place, or did it emerge that it was the most natural way to tell the story?

I had that going in. Apocalypse Now is as famous a making of story as there could be, and it’s not just a great story, but it’s been told beautifully by Eleanor Coppola in her book and by the film Hearts of Darkness, obviously. But there was the part that made it an even better story than we knew with the fact that Zoetrope was on the line. That aspect of it has been lost or was less considered in this now-mythic telling of the making of the movie.

So I knew from the beginning that I wanted to start out with Francis. Now, it’s not just his family that is on the line. It’s not just that his sanity is on the line, and his movie is on the line, but his vision for the future is on the line, which is to say all of our futures are on the line. So I knew the book had to go there, and then it had to end when that vision didn’t end but when that incarnation of it ended, and that’s One From the Heart. So I knew going in that was going to be my beginning and ending. And then of course, I would have to flash forward and back along the way.

You’ve written about some of the most renowned figures in film and theater and the making of one of the greatest films of the ’70s, if not the latter half of the 20th century. How did writing this book differ from some of the other forays you’ve done into writing about film?

I thought of this book as a biography of a dream, less a biography of a person, less a making of a movie, although it has those elements of it. You’re going to get a biography of Francis, and you’re going to get making of Apocalypse Now and One From the Heart, but you’re also going to get the beginnings of Zoetrope, which precedes those, and you’re going to get the future of Zoetrope, which follows them.

So it’s a biography of a dream. On the one hand, that freed me from having to go through the play-by-play of Francis’s later work, which is a disappointment to me and I think a lot of us. It freed me, but it was also in a way overwhelming. How do you characterize a dream? Where does a dream begin? Where does a dream end? So in that way, it was challenging and freeing, not knowing I wasn’t going to do a cradle-to-grave story. But once I found the shape of it, I was off and running.

Did writing The Path to Paradise change the way you view any of Coppola’s films or all of his films? Were there some that became higher in your estimation after you had gone through the process of writing this book, or did you find your feelings about his filmography were relatively similar?

Basically, relatively similar. My feelings about him had changed. My admiration for him, which was already high, went even higher. As far as the film work goes, I have a deeper love of Rumble Fish. Maybe The Conversation, I would say, would be slightly overpraised. I would modulate that one down a little and Rumble Fish up. And also The Outsiders — I’m a fan of The Outsiders. And Francis’s work as a producer, I fell even harder for. The films with Carroll Ballard. American Graffiti, which I think we can all agree is George Lucas’s best movie. Even the Star Wars people would have to agree, I would think.

You wrote a little bit about Coppola and Lucas stepping in to help Akira Kurosawa get some of his films made, and I’m also a huge fan of Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. When I’d see Coppola’s and Lucas’s names on films like that, it heightened my opinion of both of them because they weren’t just making their own films, they were also helping some really fascinating projects by other filmmakers get made.

That was a big impulse for me writing the book, too: Francis as showman and Francis as Medici. And I think his work for others, his work for Zoetrope, is as great a dream as anyone has ever dreamt about the movie business. And so that’s a gift for me on par with The Godfather, which is only just a great movie. Zoetrope is a great dream for all of us.

You talked a little bit before about creating and sometimes failing. Do you think that explains why we’ve seen Coppola go back to a number of his older films and re-edit them? It seems like he’s revisited everything from The Godfather Part Three to Dementia 13 in recent years.

It’s a work in progress for Francis. And it’s amazing, actually, that it’s not true of more people.

Revisiting “One From the Heart,” the Film That Almost Bankrupted Francis Ford Coppola, 40 Years Later

The movie turned the beloved director into a Hollywood outsiderIf you were to suggest a starting point for Coppola’s filmography to someone who’s never seen any of his work, where would you recommend they start?

It would depend on who that person was. Because it can go wrong if you start at the wrong place for the wrong reasons. You could get the wrong idea about a filmmaker or a novelist or composer and carry that with you erroneously for your life. So it would really depend. I don’t know. What about you?

I’m honestly not sure. For me, I saw the first two Godfather films first. But looking at his broader filmography, I’m not sure if that’s necessarily the most representative of his work. That said, I’m also not sure there is a theoretical film buff who would be interested in watching Coppola’s films who hasn’t seen any of them already.

When it comes time to turning people on to movies, I think the most important thing is to watch them with people who love them deeply. And that could transcend whatever hesitancy a person has around the movie. My dad showed me The Godfather when I was young. Most people have this experience — their father showed them The Godfather, right? It’s almost an initiation at this point. And I think that has a lot to do with why the movie continues to be a part of the culture because it’s not the only great movie that we’ve made. However, it is one of the few movies whose greatness has been passed down from generation to generation.

And if you hear about how people first saw The Godfather, it’s because somebody who loved it, who was an older figure of authority, sat down and said, “Here’s why you should love this.” A lot of times we turn people onto movies. We leave them to grapple alone with the movie, which is oftentimes less productive than actually being there for the movie, even sitting with them in the moviegoing experience.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.