![]() f the 1980s produced a rival, or even a genuine spiritual heir, to the great American naturalists — Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Teddy Roosevelt, John Olmsted — we must consider the unlikely case of Jack Longacre, a long-distance truck driver, trailer park owner and writer who lived within sight of Taum Sauk, the highest point in Missouri. That last was no accident, and it nods to the final, and most salient, entry on his resume: founder of the Highpointers Club.

f the 1980s produced a rival, or even a genuine spiritual heir, to the great American naturalists — Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Teddy Roosevelt, John Olmsted — we must consider the unlikely case of Jack Longacre, a long-distance truck driver, trailer park owner and writer who lived within sight of Taum Sauk, the highest point in Missouri. That last was no accident, and it nods to the final, and most salient, entry on his resume: founder of the Highpointers Club.

In October 1986, Longacre wrote an open letter to the editor of Outside Magazine, noting that he had observed, in his own hiking to the tallest peaks of various states, “a pattern of comments in [summit] registers in reference to the state highpoints: ‘This was my 21st state H.P. …’ ‘This was my 12th …’ … My God! I thought. There must be others out there with no more sense than myself, and I’d like to meet or correspond with them.”

Of the 30 people who wrote to him, seven joined him in a motel room in L’Anse, Michigan, in April 1987, for what would be later regarded as the first Highpointers’ convention. The focus was an assault on Mount Arvon, which surveyors had determined to be 11 inches taller than neighboring Mount Curwood, unticking that box on the highpointers’ lists. “He had already been to Mount Curwood, but not to Mount Arvon,” Jack Parsell, who attended that first meeting, told me on Campbell Hill, the site of the 2011 Highpointers Convention and the highest point in Ohio. (Parsell, a woodworker, ski patrol volunteer and chemical engineer, died in 2015, at 93.) His first highpoint was New York’s Mount Marcy in 1939, when he was 17; he finished his fiftieth exactly 50 years later, at the 13,089-foot Gannett Peak, Wyoming’s highpoint and one of the pursuit’s biggest challenges.

(Highpointer trivia: Theodore Roosevelt had just summited Mount Marcy when a guide alerted him to President William McKinley’s imminent death — and Roosevelt’s impending presidency.)

Mount Marcy, NEW YORK

The year after the Michigan expedition, Longacre reserved a restaurant’s event room for a convention in Flagstaff, near the Arizona highpoint at Humphrey’s Peak. “He didn’t expect more than 20, he made a commitment for 30, and he had his fingers crossed that enough people would show up to pay the bill at the restaurant,” Parsell said. Over the next few years, the club swelled from eight to 30 to 90 to its current tally of about 1,500, and nearly three decades after the “original eight” met up in Michigan, hundreds of highpointers annually gather in an elevated corner of the country every summer. In 2016, they met at Red Lodge, Montana, near Granite Peak, a 12,800-foot summit in Montana’s Bear Tooth range; next year, they’ll travel to Massachusetts’s Mount Greylock, a “drive-up” highpoint topped with a memorial tower that pays tribute to veterans.

Highpoint conventions share certain elements, including the one that will be held next July 20-22 at Mount Greylock: There will be a meeting of the board of directors. There will be a pancake breakfast (next year, at the Golden Eagle Restaurant in Clarksburg, Massachusetts) and watermelon awaiting hikers at the summit, one of Longacre’s traditions. Other events are up to local organizers. Suggestions for next summer include a visit to Susan B. Anthony’s birthplace and Cessna flyovers of the Berkshires.

* * *

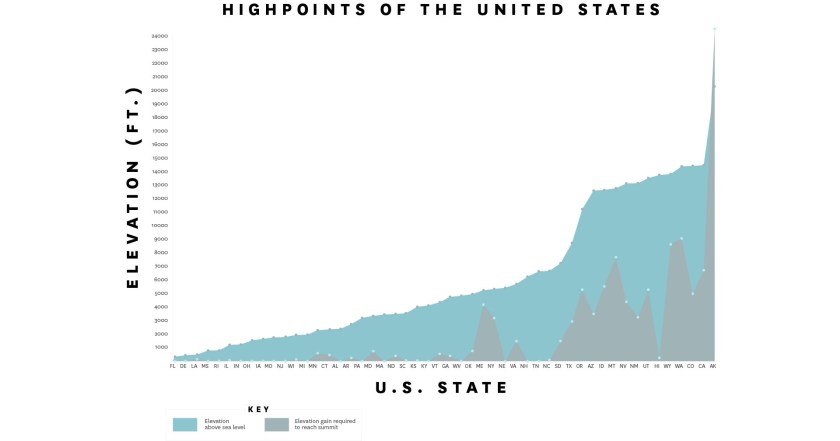

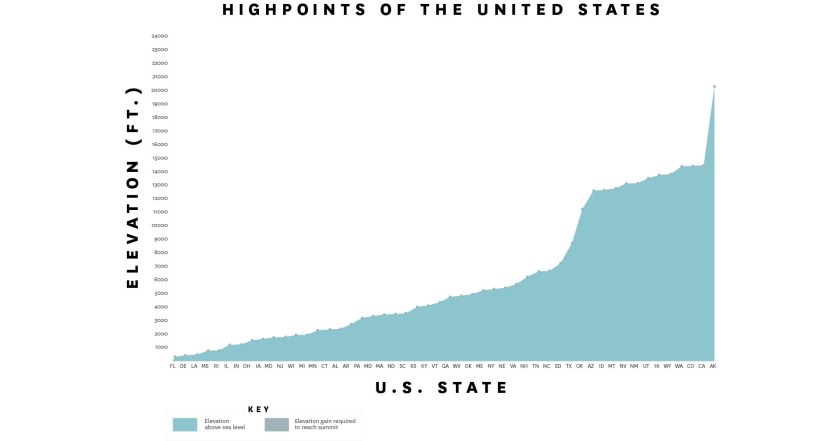

t each of the conventions, special regard will be extended to 50-state highpointers, who’ve summited peaks ranging in altitude from 345 feet (Britton Hill, Florida) to 20,310 (Denali, Alaska). “Back in ’95, I had … let’s call it male ‘mental-pause,'” highpointer Kenny Pokera told me, when we met on a patio above an indoor pool at the Emerald River Hotel in Sheffield, Alabama. “And I decided I wanted to climb Mount McKinley.” After a 10-day mountaineering course and three weeks on the mountain, he summited Denali, and he was hooked — not on ice climbing, per se, but on highpointing. “You get on a mission, if you want to call it that. You gotta do Nebraska, you gotta go to Kansas, you gotta do Briton Hill in Florida. I would never have gone to Florida; I would never have seen Sassafras Mountain [in South Carolina] without it. All of a sudden, you’re seeing areas of the country you’d never thought of coming to.”

t each of the conventions, special regard will be extended to 50-state highpointers, who’ve summited peaks ranging in altitude from 345 feet (Britton Hill, Florida) to 20,310 (Denali, Alaska). “Back in ’95, I had … let’s call it male ‘mental-pause,'” highpointer Kenny Pokera told me, when we met on a patio above an indoor pool at the Emerald River Hotel in Sheffield, Alabama. “And I decided I wanted to climb Mount McKinley.” After a 10-day mountaineering course and three weeks on the mountain, he summited Denali, and he was hooked — not on ice climbing, per se, but on highpointing. “You get on a mission, if you want to call it that. You gotta do Nebraska, you gotta go to Kansas, you gotta do Briton Hill in Florida. I would never have gone to Florida; I would never have seen Sassafras Mountain [in South Carolina] without it. All of a sudden, you’re seeing areas of the country you’d never thought of coming to.”

PANORAMA POINT, NEBRASKA

For many, the quest extends into multiple decades. “I think lots of people start when they’re 30 — and hey, guess what? You’re 45 when you finish,” says John Mitchler, a 50-state completer and the editor of the club’s newsletter, Apex to Zenith.

And once they complete the list? Some simply start over from the beginning. Pokera is on his third tour through the 50 highpoints; when I met him at the convention in Alabama, near the highest point in Mississippi, he was on number 110. “I started the third trip around after 60 years of age,” he told me, “so if someone is silly enough to try it for a third time, to do better than me I guess you’re going to have to do it after 60. But I’ve got 39 to go — Denali, Gannett [Peak in Wyoming], Granite [Peak, in Montana]. None of them are gimmies.”

Pokera’s wife Donna sat quietly beside him in a plastic pool chair as he reeled off his plans. At the time, they were a week short of their 28th anniversary. “I thought he was absolutely out of his mind,” she said. She stayed at home while he worked his way through the Seven Summits: Argentina’s Aconcagua, the highest point in the Americas; Mount Vinson in Antarctica; Mount Wilhelm in Papua New Guinea, the highest point in Oceania.

“In Papua New Guinea, not only did the climbing worry me, but his life worried me — there were guerrillas, with machine guns, and that was just blowing my mind,” she said. “I love to do these things, but he’s an extremist. I appreciate it, but I would like to do them with a little bit more moderation.”

Donna Pokera has accompanied her husband on all but six of his American highpoints, and she has seen firsthand the unique psychological makeup that highpointers possess: a sense of whimsy and a love of nature that derives its power neither from a Romantic affinity for wandering nor the aimless wonder of the flaneur but a wildly diverse — and distinctly American — set of values. While climbing Denali requires the classical mountaineer’s constitution (courage, fortitude, resourcefulness), trekking to the highest point in Delaware begs something more perverse: whimsy, doggedness, a sense of humor.

“They’re all insane,” she said. “They’ve all done insane things, where they’ve driven miles and miles — one of the hardest things is that to get to all these places, you have to drive thousands of miles — and you’re half asleep, and then when you get there, you have to pursue these mountains, which the weather doesn’t always permit. We’ve been in white-out situations where we’ve had to turn back, and we’ve been in white-out situations where we didn’t turn back. I’ve actually hated him for it, and said, ‘We shouldn’t do this — the sign says there are white-out conditions, to turn back.’ And he says, ‘Oh, no. That’s for someone else. That’s not for us.'”

I asked if she’d be accompanying her husband on his third tour of the highpoints. “I don’t want to do that,” she replied. “Personally, I’m OK with not wanting to do that.”

She had all but the biggest western peaks: Granite, Gannett, Hood, Rainier, Borah, Denali. “When I got to 44,” she said, “I told myself, ‘That’s 44, and there ain’t no more.’”

* * *