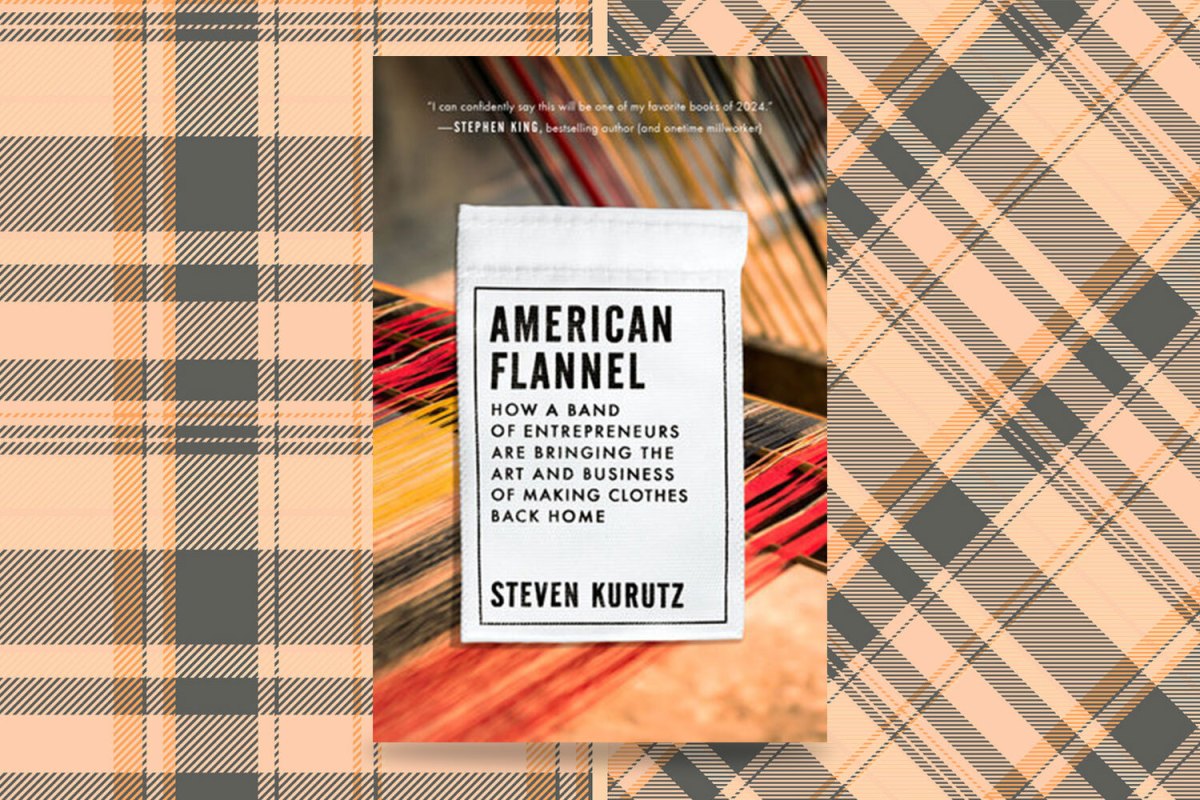

There are two big themes that suffuse American Flannel: How a Band of Entrepreneurs Are Bringing the Art and Business of Making Clothes Back Home, the new book from Steven Kurutz. The first has to do with the perennial search for high-quality clothing — in other words, something that can last for years and still look good in the process. The other is the decline of manufacturing in the United States — and it’s not surprising that Kurutz finds an innate connection between these two ideas.

Throughout American Flannel, Kurutz chronicles the challenges facing different companies — including both longstanding businesses and startups — trying to keep their footing in an ever-shifting market and produce high-quality clothing that people will want to wear. It’s a complex and urgent story, made even more gripping by Kurutz’s focus on the bold personalities within this space.

InsideHook spoke with Kurutz about the genesis of American Flannel, how writing the book changed Kurutz’s own buying habits — and how the rise of companies like Shein factor into things.

InsideHook: Early in American Flannel, you mention American Giant founder Bayard Winthrop being drawn to his industry via a favorite shirt. Do you have a similar origin story in terms of your own interest in the more human-scale aspect of this industry?

Steven Kurutz: I grew up near the village of Woolrich, Pennsylvania, home to the eponymous workwear brand that originated the lumberjack flannel shirt. It’s a mountainous, remote area, and Woolrich gear was commonly worn, especially during hunting season. (Head-to-toe buffalo plaid is a “Pennsylvania tuxedo.”) Having such a revered heritage brand in my own backyard no doubt informed my early appreciation for American apparel. I’ll add that my maternal grandfather was a stylish dresser in the classic American sportswear vein and my biggest style influence growing up. He didn’t have a lot of money but he appreciated quality and bought the best clothing he could afford, like Woolrich, Eddie Bauer and L.L. Bean.

How did you settle on the companies that you wound up covering in your book? Were there any designers or manufacturers who you had difficulty contacting?

I didn’t choose the companies so much as they chose me. When I met Gina Locklear, the founder of the organic sock brand Zkano, who runs a hosiery mill in Fort Payne, Alabama, and later Bayard Winthrop of American Giant, I found them both remarkable people, though in different ways. Bayard was an outsider coming into the apparel world — he knew next to nothing about making clothes — but he had a sense of mission around reviving U.S. manufacturing and big ideas and energy. Gina is quieter, but she has a steely resolve. She’d grown up in her parents’ sock mill, saw the local industry collapse due to offshoring and returned home determined to reinvent her family’s business. I profiled both Gina and Bayard for The New York Times and their stories stayed with me long afterward. I wanted to continue to follow them and see how their careers and lives developed.

Was there one aspect of researching or writing American Flannel that was especially challenging for you?

The structure was a challenge. For far too long, the book was organized as a series of long essays, each one about a different company or maker. That form wasn’t working — it had no narrative drive, no oomph. Luckily, my editor, Rebecca Saletan, is an ace at structure and saw a way to crack apart those essays and create a narrative arc from the pieces. The spine of the book follows Bayard’s efforts to make a flannel shirt in America again. That turned a book about clothing into a quest story.

Your book looks at a number of companies that are looking to revive certain methods of making clothing. In recent years, there have also been heightened efforts to unionize different workplaces — and while seemingly different, they also both seem to be a way of addressing the deindustrialization that took place in the U.S. decades ago. Do you see the two phenomena as being interrelated?

I do. Fifty years ago, America began shipping its manufacturing overseas and decided it was going to be a consumer economy that relied on debt and financialization to spur growth. That doctrine was promoted at the highest levels of Washington and Wall Street, without a lot of thought as to what would become of the local communities and workers who were reliant on those manufacturing jobs.

Fifty years later, after so many American towns and cities got hollowed out, it’s become clearer that losing our manufacturing base in exchange for cheap, foreign-made TVs and sneakers was not a good tradeoff. The unionizing efforts at Amazon and other companies, as well as the recent victory by the striking UAW, are part of a long overdue recognition of the value of American workers. In short, I think we recognized what we lost — including the ability to make a flannel shirt.

Something that struck me as interesting about your book is the way it points to one trend in clothing — to wit, returning to the idea of paying more for a better-made, longer-lasting garment. At the same time, we’re also seeing the growth in companies like Shein, which seem to take the exact opposite approach. Do you think we’re about to see a greater sense of polarization within the industry?

Ah, the S-word! Just when you think the idea of “buy quality, buy less” has taken hold in the broader culture, along comes another fast fashion retailer to capture consumers’ desire for novelty and cheap stuff. Frankly, the popularity of Shein at this moment in time baffles me, and I do worry about what it says about our commitment to sustainability and ethically produced clothing.

How far into researching this book were you when the pandemic happened?

I’d already spent a lot of time immersed in the world of U.S. apparel manufacturing through my reporting for The New York Times. But I sold the book to my publisher in March 2020, so just as I was ready to hit the road and do more reporting, the world shut down. For months the only reporting I could do was via phone, which was challenging and not nearly like the fun of hanging out with your subjects.

In American Flannel, you discuss some of the ways in which COVID-19 affected the companies you wrote about. Were there any larger or structural ways in which the pandemic completely altered something you’d planned for the book?

The book asks these questions like, “What does it mean for a country to lose the ability to make things?” And, “Was globalism a good tradeoff for American communities?” The pandemic made those somewhat abstract ideas real. Americans saw images of doctors and nurses wearing trash bags and bandanas because the country didn’t have the ability to make PPE. We’d ceded that capacity to China. What the pandemic did, really, was give the book an ending and a kind of weight it might not otherwise have had.

The Best Flannel Shirts to Channel Your Inner Lumberjack

Bring a some Paul Bunyan energy to the partyOne of the running themes in your book is the precarity that even successful businesses have — especially in terms of a lack of institutional memory. Do you think there will be a kind of tipping point where one person retiring wouldn’t put an entire business at risk, as you describe in one chapter?

That depends on whether we as a country decide to reinvest in manufacturing, and whether some of the bigger clothing brands return at least some of their production onshore. If so, the industry can get economies of scale, manufacturers will have steady orders and young workers can be trained up again and develop expertise as they once did.

Either way, though, the Gina Locklears of the world will find a way to stay in business. As Gina told me, “I’m not a sock seller. I’m a maker. It’s hard every day. But I still love it. It’s what I want to do forever.”

Did researching and writing this book change the way that you shop for apparel?

Yes. It’s given me a greater appreciation for what’s involved in making clothes. When Bayard succeeded in making an all-American flannel shirt and then sent me one, it practically glowed in my hands. I could not separate the shirt itself from all the work that went into it and the hundreds of people along the supply chain who had a hand in its creation. I don’t think I’ll ever again look at a flannel shirt, or any item of clothing for that matter, as a throwaway purchase.

Are there any companies that you’d recommend interested readers check out if they’re looking to seek out well-crafted and American-made garments?

I am partial to Zkano socks and American Giant T-shirts. Another company I write about in the book is Rancourt & Co., a shoemaker based in Maine that employs some of the last hand sewers in America. They make “some damn fine shoes,” as one of their customers is quoted as saying. There’s also Citizens of Humanity, which makes its jeans in Los Angeles. And Chatham blankets, a wool blanket company that traces its history back to the mid-1800s. And Gamine — a line of cool workwear for women founded by a Rhode Island gardener. The funny thing is, even though U.S. apparel makers represent a tiny fraction of the marketplace, the more you look for these companies, the more of them you find.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.