Early on in Part 1 of Netflix’s jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, there’s a seemingly innocuous moment that winds up hitting like a ton of bricks. It’s 2002, and Kanye West is playing pool with some friends and collaborators at his apartment after working on the early seeds of what would eventually become his debut album, The College Dropout. The TV is on in the background, and it’s playing an interview with R. Kelly about the recently leaked sex tape — or, more accurately, rape tape — on which the singer can be seen sleeping with (and most infamously, urinating on) an underage teen girl. The reporter asks Kelly point blank, “Have you ever made tapes, sex tapes?” As Kelly struggles to offer a clear answer onscreen, a smirking West mocks him, faux-stammering, “If they have a tape of me, I mean, they’re saying it’s of me…” before trailing off and laughing.

It’s staggering for a number of reasons. For one, it’s a painful reminder that it took nearly 20 years for Kelly to face any real consequences for his actions. But it’s most striking to see West — who would go on to draw plenty of ire for tweeting “BILL COSBY INNOCENT !!!!!!!!!!” in 2016 — presuming Kelly actually did what he’s accused of and laughing at how obvious his guilt was. How did that Kanye, the one who pounced all over Kelly’s total inability to defend his indefensible behavior, turn into the Kanye who dismissed the pain and suffering of the more than 60 women who claimed to be sexually assaulted by Bill Cosby? How did he become the Kanye who, in 2020, changed his tune on Kelly entirely and claimed that the “Ignition (Remix)” singer was “taken down by white media“?

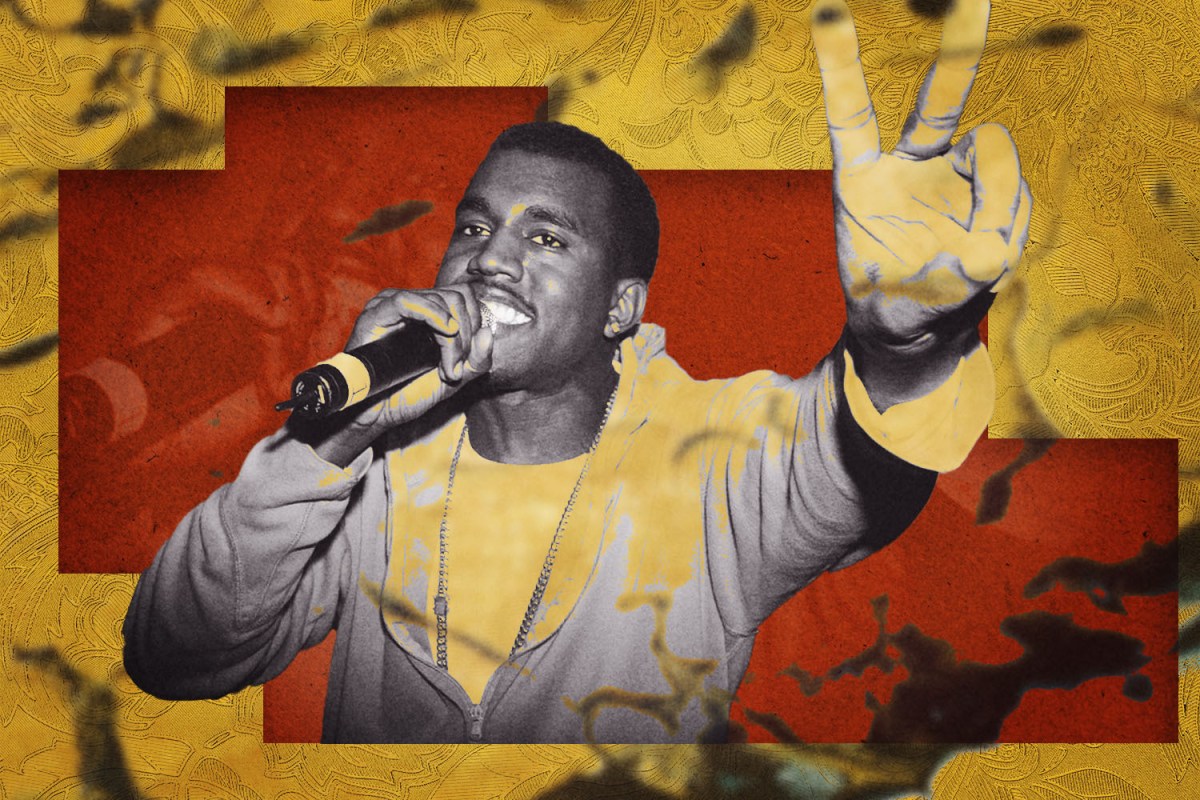

We may never know how, but the three-part documentary from directors Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah (better known as Coodie & Chike) is full of harrowing reminders of the Kanye West that once was, and how he stands in contrast to the frustratingly problematic tabloid darling he’s since become. The four-and-a-half hour doc was culled from more than 300 hours of footage recorded over roughly 20 years, starting in 1998, when Coodie — then a Chicago public access TV host — discovered a young West and gambled on the fact that he’d one day hit it big. Part 1, which is now streaming, chronicles his early attempts to get signed by Roc-A-Fella Records and be taken seriously as a solo artist after his early success as a producer making beats for other people. Part 2 deals with the aftermath of the car crash that inspired “Through the Wire” and focuses on The College Dropout and his breakthrough success. It’s not until Part 3 that we meet the Kanye(s) we’ve all been grappling with in recent years — the MAGA hat, “slavery was a choice” Kanye, the one whose delusions of grandeur led him to run for president in 2020, and of course, the man who is very clearly struggling to cope with a serious mental illness. (Parts 2 and 3 premiere on Feb. 23 and March 2, respectively.)

jeen-yuhs isn’t perfect. Its journalistic ethics are a little dicey, given the obvious friendship between Coodie (who also narrates the documentary) and West. There are parts where our director unnecessarily turns the camera on himself, injecting his own story into the narrative. There’s a big gap in its coverage, thanks to the fact that the two fell out of touch for years after the rapper became a superstar, and we miss out on any firsthand accounts of some major moments from his career. When West invites Coodie back into the fold in 2017 to film him once again, Part 3 is off to the races, but it also reportedly features some upsetting footage of him in the throes of a manic episode that have led some to question whether it’s exploitative. (West was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2016.) At one point, while in the Dominican Republic chatting with potential real estate investors, West becomes increasingly incoherent and paranoid as he references the 5150 involuntary psychiatric hold he was put on in November 2016. “Have you guys ever been locked up in handcuffs and put into a hospital because your brain was too big for your skull? Okay, I have,” he said. “There’s an execution style that was performed on me over the past six to seven years, post Taylor Swift. Where they tie one arm — both arms, both legs to four horses in all different directions. Boom! Bah!” Coodie cuts off the camera after that moment, perhaps himself questioning whether it’s right for us to be leering at someone who’s not in their right mind.

But despite its issues, jeen-yuhs makes for fascinating (if not deeply frustrating) viewing, especially given all the attention West has brought upon himself in recent days by harassing his ex-wife Kim Kardashian and her current boyfriend Pete Davidson. Part 1 in particular feels like a sad reminder of what might have been if he’d just been able to keep it together, rather than self-destructing via a toxic combination of mental illness, hubris and misogyny. Even when we see him desperately playing a demo of “All Falls Down” for a visibly uninterested Roc-A-Fella assistant, his talent is undeniable — which makes it all the more disheartening to think of how he’s since squandered it. The scenes with his mother Donda (who passed away due to complications from cosmetic surgery in 2007) raise the most questions: How can a man who had such an obviously strong love and respect for the woman who birthed him wind up treating the mother of his own children like a possession that has been “stolen” from him?

Watching Kanye with Donda is almost like watching an entirely different person. When she speaks, he instinctively bows his head and listens, trading his usual intense gaze for a soft, almost bashful glance at the floor as he quietly takes in what she’s saying. (In one particularly telling scene, she warns him about coming off as too arrogant, telling him, “The giant looks in the mirror and sees nothing,” and we can see flickers of shame in his eyes as he nods and accepts the constructive criticism.) His deep reverence for her is plain as day, and it’s easy to see how her death completely derailed him; without her — his rock, the only person capable of keeping him tethered to earth — he veered off and became the trainwreck we all now know all too well. Looking back now, after days of cringing while reading about him stalking Kardashian or his pattern of throwing out his girlfriends’ entire wardrobes so he can cultivate new “styles” for them, dressing them up like Barbie dolls he can control rather than women with agency over how they want to present themselves, it seems impossible. How do we reconcile his glaring latter-day sexism with the fact that the single most important person in his life was a woman?

The truth is, West’s problematic attitudes toward women were always there, in his work (see: “Gold Digger,” “Famous,” his recent decision to work with accused rapist Marilyn Manson and many more examples) as well as his personal life, long before Donda died. Even that R. Kelly moment from the beginning of the doc feels darker the more you think about it; his reaction to the singer allegedly being caught on tape raping a child was laughter at Kelly’s ineptitude rather than horror or disgust over the obvious trauma his victim must have endured. His mental illness has perhaps made him more likely to impulsively tweet something vile about women or obsessively, publicly harass female celebrities with little to no regard for any potential consequences, but being mentally ill doesn’t make you sexist — that aspect of West’s personality was always hiding in plain sight, completely unrelated to his mental health. And yet, the guy sure did worship his mom.

So what are we supposed to do with all of this? jeen-yuhs doesn’t offer any real answers or clear arguments as to how we should feel about this deeply polarizing, clearly complicated and extremely flawed artist. But it does raise tough questions by presenting us with revealing fly-on-the-wall footage of his rise and glimpses of his sad descent. Are we right to empathize with him? It’s hard to say. (Is it possible to simultaneously feel extremely sorry for him because he has to live with an illness we wouldn’t wish on our worst enemies — one that has made him the butt of cruel late-night jokes for years — and also disgusted by the beliefs and attitudes that have nothing to do with that illness?) Given everything currently going on with him, jeen-yuhs brings an important new layer to the conversation, adding some fresh context and forcing us to confront how we feel about the 21st century’s most divisive superstar.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.