He made the alt-right’s day.

When Director Don Siegel described his titular anti-hero in Dirty Harry, he was well aware of the danger he’d unleashed on the American imagination: “I was telling the story of a hard-nosed cop and a dangerous killer. What my liberal friends did not grasp was that the cop is almost as evil, in his way, as the sniper.”

Along with movies like Death Wish and Falling Down, the armed avenger, having been pushed to his limits by violence, grief or injustice, feels justified in strapping on a gun and letting loose, forget the collateral damage. And by romanticizing that ultra-American antihero — the lone cop, the wronged husband, the downsized and foreclosed — they have contributed to a culture for the alt-right romanticizing the idea of a lone gunman taking down a corrupt system.

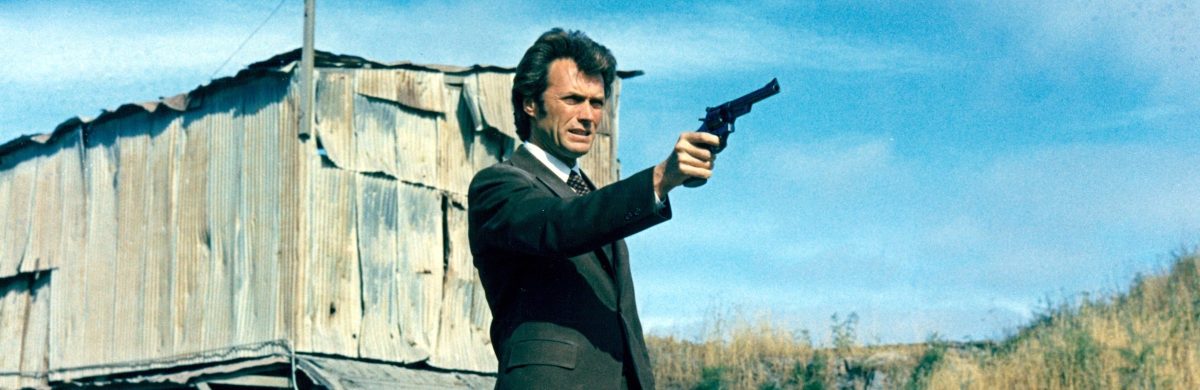

Clint Eastwood became an American icon as cowboy cop “Dirty” Harry Callahan in 1971. The film touched a raw nerve and served as a model for vigilante movie cops for years to come. The knockabout actor and jazz musician from San Francisco, California came to embody that lone American on the edge of the frontier who hopped off his horse, touched his tarnished Sheriff’s badge, and faced down chaos with a dose of kickass.

Callahan and his Smith & Wesson 44 Magnum, the product of American industrial superiority, were a law unto themselves. Miranda Rights are for sissies. This cop is an individual largely detached from familial, romantic or religious connections that could restrain or channel his primal violent urges. Justice without mercy animated cynical Callahan’s intimidating catchphrase delivered over his gun barrel to quivering villain Scorpio:

“Do ya feel lucky?”

Critic Pauline Kael called the film “fascist” and “immoral.” (Nixon, meanwhile, praised it and invited Eastwood to the White House.)

Over at Jacobin Magazine, in the intro to an extract of Patrick Gilligan’s biography of Clint Eastwood, the editors wrote: ” the iconic status of one of Eastwood’s most defining films, Dirty Harry, is attributed to a conservative longing for national confidence, power, and social order, all seemingly eroded by foreign military defeats and domestic civil rights and protest movements. Eastwood backed Nixon for the presidency shortly after the film’s release, thereby explicitly lending his star power to issues for which the Dirty Harry character stood as a perfect symbol.”

As Eastwood continued to be wild about Harry for another four films, broody Charles Bronson played avenger as NY architect Paul Kersey in the grim 1974 crime classic Death Wish. In a plot point normalized by Walt Disney, who had no trepidation killing off fictional family members to launch a plot (Oh, poor Bambi!), the anti-hero’s wife is killed and their daughter raped by three intruders in pre-gentrified Manhattan. This throws Kersey’s hate-and-rage switch. It also steadies his trigger finger.

Like a frontier vigilante, widower Kelsey confronts the black hats with the only lesson they’ll apparently heed: violence. The question dangles – once you’ve cleaned the scum off the street, who’s going to clean the blood off the sidewalks? Like Dirty Harry, this franchise had four sequels plus this year’s reboot starring Bruce Willis.

Joel Schumacher’s controversial 1993 rage-fest, Falling Down is a divisive entry, perhaps because divorced defense contractor William Foster (Michael Douglas) is so clearly cracked. What’s an unemployed and emasculated white collar worker going to do when his expectations decline? Snap.

Douglas’s Kelsey can’t change those elements constricting him – personal, professional, even the weather’s against him. Changing himself is out of the question. So the guy gets a gun and explodes as the LA riots combust in the background. He runs amok.

These movies give audiences escaping from trying times a false sense of control by witnessing a single man taking unilateral action against chaos. Yet, how many recall that at Dirty Harry‘s climax, evil sniper Scorpio hijacks a bus full of school kids. Their lives weigh in the balance for our entertainment. Can we see school shootings as a corollary, in that the killer who is revved up and hungry for vengeance on a larger stage, feels no empathy for the individuals in his wake?

Lately, as we watch the lone gunman scenario unspool again and again in real life – in Pittsburgh, Pa., Parkland, Fla., and Las Vegas, NV — the slaughter of the innocents begins to meld into a mass attack against unarmed Americans. Taken together, the jacked-up lone wolves have become a pack. (And I’d argue in Donald Trump and his angry, enabling rhetoric, it seems they have found their alpha dog.)

In their minds, laws are made to be bent. And, if these movies, and similar ones that followed, are any guide, when cornered they will come out shooting.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.