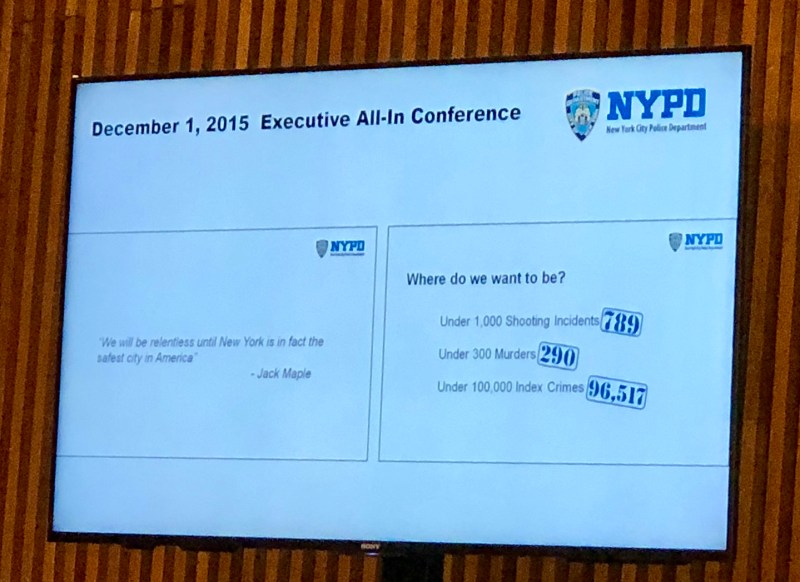

Back in 1990, New Yorkers might not be able to fathom a time when murder wouldn’t be part of their daily lives. That year, more than 2,200 people were murdered in New York City. But after three decades of declines, the murder rate in 2017 was down to 290. The significant change marks a trend that has been occurring for 27 straight years: violent crime in the city keeps dropping in every borough.

“(This year) will go down in history as the safest year we’ve seen in nearly seven decades, that span covers three generations of New Yorkers,” said Commissioner James P. O’Neill, of the New York Police Department, during a year-end crime press briefing held at NYPD Headquarters on Jan. 5.

The last time the murder rate was this low was in 1951. According to Mayor Bill de Blasio, there has been a 93 percent reduction in stop and frisk, a controversial policing tactic, which has been accompanied by the lowest crime NYC has ever had.

“That’s proof-positive that we used to be making a mistake in this city, we stopped making that mistake, we made ourselves safer,” he said at the January press briefing.

There were also 30,000 fewer arrests in 2017 than 2016.

“Today’s statistics prove that New York City is the safety it’s ever been,” said Speaker of City Council Corey Johnson, at the NYPD crime press briefing. “It is hard to even comprehend.”

So what has caused such a constant, and drastic, reduction in crime? According to Deputy Commissioner for Public Information Stephen Davis, who has seen close to 50 years of policing, there are a few key reasons, all of which work together: community policing, more officers on the street and precision policing as well as the use of new technologies.

Adding More Officers to the Force and Beginning Community Policing

Back in 2015, the NYPD made two big moves: adding more officers to the force and starting community policing.

According to Commissioner Davis, the NYPD employs about 52,000 people. Out of that number, 36,000 people are uniformed police officers and 16,000 people are in civilian positions, such as maintenance staff, legal staff, car mechanics and more. Two years ago, the NYPD added about 1,300 new police officers and 700 civilian positions.

That same year, the NYPD divided precincts into four or five fully staffed sectors, that work within the boundaries — as much as possible — to the boundaries of actual existing neighborhoods. The goal was to build trust in the community and make people feel safer.

Commissioner Davis told RealClearLife that the NYPD had a lot of problems with trust, because a lot of trust was lost during “hard-handed policing.” He said when people don’t trust the police, they are not willing to work with the police, and therefore, crime fighting was not being done as efficiently as it could. Commissioner Davis said that building trust, just like lowering crime rates, does not happen overnight, but when the community starts to learn that officers are there, and they’re going to be there tomorrow, and the next day, that they are attempting to be a part of the community, “something develops.”

“The more you trust, the more the word gets out, the more you get positive feedback, then it works,” he said.

During the Jan. 5 briefing, Mayor de Blasio listed examples of crimes that were stopped because community residents had gotten to know the cops who patrolled their area and had called them. Those crimes included drug hubs, illegal weapons and suspects of multiple robberies.

“Technology is great … but I think the best thing we offer is the ability for police officers to establish their relationships with the people in this great city,” said Commissioner O’Neill at the January press briefing.

The NYPD is planning on continuing this policing policy into 2018.

“We’ve got a new baseline, a new normal, and that normal is going to fluctuate, but we’ve got so many systems in place, and now we’ve got people in place, and I don’t mean boots on the ground, I mean people communicating with people, people really dealing with people on a very, very, personal basis that makes them feel like they got ownership of their own precinct sector, and the people in the precinct-sector feel like they’re got a cop, not a cop from the 24th precinct, they got Joe, and they got Tom and they got Jane, and that can only help,” Commissioner Davis told RealClearLife.

The Move to Precision Policing

Commissioner Davis started with the police department in 1969. He said back then, “you cared about your own house,” in regards to working with other cops outside your designated precinct. There was no technology — they didn’t even have enough radios — that allowed officers to track crime or look at overarching patterns and there wasn’t an environment of sharing information across neighborhood borders. Accountability and resources were both low.

So the NYPD created the Organized Crime Control Bureau (OCCB), which put everything under one bureau, including vice, prostitution, mafia, sex trafficking and gangs. Chief of Detectives Bob Boyce, who had joined the force in 1983, was put in charge of the bureau. Boyce had a “wealth of knowledge of many disciplines and areas of the city,” Commissioner Davis said.

They decided to take a new approach on arrests — instead of arresting one person on the street, who can easily be replaced, the NYPD started building cases against the biggest perpetrators of crimes.

Commissioner Davis described it as fighting yellow jackets. He said instead of swatting yellow jackets on his back porch, because a different yellow jacket will always come back, he instead finds and destroys the nest.

“In 2016, we took down approximately 100 what were called gang cases,” said Commissioner Davis. “They could be as small as five guys selling narcotics on a certain street up in the Bronx, five guys doing a stolen credit card scam, five guys doing burglary out there in Queens, or as many as 100 guys in one pop in the Bronx.”

The NYPD, using technology and better communication, started to bring the main players of crime out the equation and putting them behind bars through major cases.

Commissioner Davis believes this is “the most significant cause” of the drop in crime.

“No coincidence in my mind, and upon analysis I don’t think anyone can challenge it, all of a sudden now, having done that intensely in 2016, now in 2017 you see a dramatic reduction in shootings, and in homicides, which are the two crimes that are closely associated with those activities,” he said.

Commissioner Davis also said that now there is better communication, computer programs like CompStat to track crime, more accountability, and one bureau. Though tracking crime and communicating between precincts now seems like a “no brainer,” he said that “in those days, we were so damn busy that all you could do was go from day to day, hour to hour, putting out fires, dealing with drugs, the shootings were phenomenal.”

The Outlier

Not every category of crime has dropped in New York City. There was an increase of four rapes from 2016, with a total of 1,446 rapes in 2017.

“It is a stubborn crime and we have work to do still on that front,” said Chief of Crime Control Strategies Dermot Shea during the January press briefing.

Will Crime Rates Keep Dropping?

NYPD officials say that these rates can go even lower.

“I believe we can go lower, we can do better, crime can be pushed further down, it’s going to take a lot of cooperation and I think we’re going to get it,” Chief Shea said.

But criminologists are not entirely sure why the declines have continued. Franklin E. Zimring, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law told The New York Times that better policing accounted for much of the thirty-year decline, but it is not the primary driver anymore. He said the reason for the decline is “utterly mysterious.”

The NYPD — and the mayor — say that the numbers will keep falling as they continue community and precision policing.

“Something very powerful is happening because of the neighborhood policing model and meanwhile, other great efforts that are happening … all of this is happening simultaneously,” said Mayor de Blasio. “This is a new day in New York City, a new reality and it’s working.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.