“I like boring things,” Andy Warhol said. Making it all the sadder that Drella was not around to witness the September 27 premiere of Baa Baa Land at London’s Prince Charles Cinema. With a run time of a mere eight hours, it features slow-motion footage of sheep in a field in England.

It also includes … actually, that’s it.

If it sounds less than electrifying to you, you’re absolutely right.

“It’s better than any sleeping pill — the ultimate insomnia cure,” declared Alex Tew. No, he’s not a film critic: he’s the film’s executive producer. Get a taste of his creation below.

Understand, Baa Baa Land is decidedly not the latest Michael Bay offering. It was produced by Calm.com, the “#1 App for Mindfulness and Meditation.” This is the rare movie where the camera capturing nothing of particular interest was a day well done.

Baa Baa Land isn’t the only recent example of slowness equaling success. In the midst of reports a human being now has a shorter attention span than a goldfish and a frightening amount of quality options in this peak TV era, Norway still debuted Slow TV. It offers programming supplying exactly that. For their debut, they put cameras on a train going from Bergen to Oslo then showed the scenery. If you have seven hours to kill and want to do so as mellowly as possible, the video below is for you.

The result is ratings gold, as roughly a quarter of all Norwegians tuned in. (It’s now available to Americans as well via Netflix, with titles including “National Knitting Evening,” which is not to be confused with “National Knitting Night.”)

Producer Thomas Hellum fully acknowledged the lack of drama, arguing that’s part of its appeal: “Much of life itself is boring. But in-between, there are some exciting moments, and you just have to wait for them.”

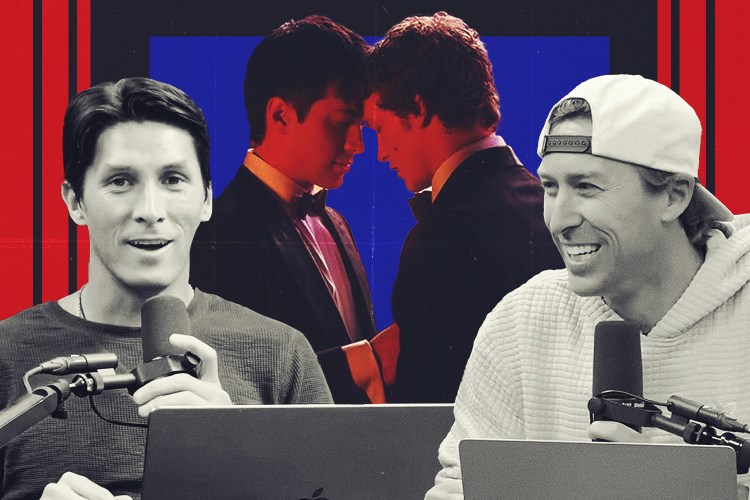

This is all part of the rise of slow cinema, a term Matthew Flanagan defined in 2008 as “the employment of (often extremely) long takes, de-centred and understated modes of storytelling, and a pronounced emphasis on quietude and the everyday.”

Warhol, of course, had a genius for being ahead of his time. His prediction of everyone being famous for 15 minutes was a prophecy of reality TV. Over 50 years ago, he helped pave the way for Baa Baa Land and Slow TV.

Land acknowledges Warhol’s influence. “Andy Warhol’s 1964 film Empire was ridiculed and mocked,” noted writer/producer Peter Freedman. “But it’s now revered as an avant-garde and slow cinema classic.” Hellum told RCL that any resemblance by Slow TV to those films was purely coincidental—”none of us had seen Andy Warhol”—and they consider Slow TV “storytelling – not actually art.”

While Warhol may be best known for paintings that can command over $100 million at auction, his legacy spans well beyond his art. He was a major figure in the lives of fellow artists like occasional collaborator Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose own work can fetch nine digits. Warhol played a key role promoting and supporting the Velvet Underground. (His name and artwork can’t be missed on their debut’s album cover.) With so many accomplishments, it’s easy for his film work to be overlooked.

Warhol’s career as a filmmaker was relatively brief, spanning from just 1963 to 1968. In 1968, Valerie Solanas shot Warhol. She had acted in one of his films and allegedly was angered he wouldn’t use one of her scripts. Only 39, he nearly died in surgery. He suffered from complications the rest of his life, including a split in his abdominal wall that forced him to wear girdles to hold in his bowels. In 1970, he withdrew his films from distribution, a policy that lasted until after his death in 1987 at 58.

Of course, Warhol’s name still appeared in cinemas throughout the 1970s. He served as producer for works directed and at least partially written by Paul Morrissey such as Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974). (They were retitled Andy Warhol’s Flesh for Frankenstein or just Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Blood for Dracula or just Andy Warhol’s Dracula.) Frankenstein even had a 3D version.

These were more conventional works than anything Warhol directed on his own. (Not that they were particularly conventional, as they flirted with X-ratings for sex and violence.) Warhol’s most famous creation from the 1960s is probably Chelsea Girls (1966), which presented the action in a split screen. It was a method both bold and not particularly easy to watch, as you can see from the clip below.

The movie won a surprising amount of distribution, it not the corresponding critical acclaim. Roger Ebert gave it one star and wrote: “Warhol has nothing to say and no technique to say it with.”

Arguably, Warhol’s most important film works came earlier and involved him doing even less with the camera. There were his famed screen tests, such as this one of Velvet Underground leader Lou Reed. Warhol slowed the film down, creating an oddly hypnotic effect.

If by the end of this clip, you were muttering, “That lasted much too long,” Empire is not for you. It’s over eight hours of continuous slow-motion footage of New York City’s Empire State Building.

To say it’s not for everyone would be an understatement, but this (along with 1963’s Sleep, in which Warhol filmed a friend sleeping for over five hours) provided Warhol a vehicle to attempt to shake the way we view film and even life itself. As Warhol said of his film work in an interview with Nigel Andrews:

“Watch a man sleep for two minutes? No; why not watch him sleep for six hours? Everything changes even when it doesn’t appear to. The meaning of Sleep, you could say, is that there is no stasis in human existence. Nor in nature. In Empire I filmed the Empire State Building for eight hours. The building didn’t change but the daylight did. That has a long and honored pedigree in art, yet when people are warned that something is ‘revolutionary,’ they don’t see the evolutionary. When Monet painted his haystacks or his Rouen cathedrals, no one said, ‘That’s enough,’ after the third one.”

So did Warhol stumble upon something profound with these minimalist yet epic works? The Library of Congress thinks so, having added Empire to the National Film Registry in 2004. Indeed, these films suggest that entertainment and even insight can come from focusing on something seemingly not that engaging if we just do it long enough. (It’s a feat we’re all capable of: that goldfish attention span story has been debunked.)

And it should be noted that Warhol didn’t want to antagonize his audience any more than the makers of Baa Baa Land or Slow TV do today. As he told Andrews: “I was not imposing these films as endurance trials. I was not saying: ‘Sit and suffer. I dare you to watch the unwatchable.’

“You could always go out for popcorn.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.