A converted pickup truck transmogrified into a giant wooden barrel is bumping down a dirt road that slices between vast fields of agave, predominantly espadín, with smaller parcels of varieties such as tobalá. A dozen people are seated on benches in the pickup’s bed, sipping on mezcal shots with more ending up on our shoes than in our mouths, given the conditions of the ride. We’re stocked with six bottles to last the next hour or two, and we’re encouraged to continue indulging as rock music blares on the speakers and the group sings along and dances in the aisle.

Rock classics from the ’80s are blasting away until a song I wasn’t familiar with pops up, though it doesn’t stop the crew beside me from singing louder than ever. That makes sense; the music is from the band SUSU, and the rowdy revelers are, in fact, the band SUSU. We’re all visiting Palenque Mal de Amor in Santiago Matatlán, a town in Oaxaca dubbed the “world capital of mezcal,” to learn about the the magic of the spirit right at its source, particularly the palenque’s work as the chief distillery partner for Ilegal Mezcal.

While I’m focused on absorbing the ins and outs of mezcal production, the band is more attuned to soaking up the vibes while preparing to head on stage the next night at Bar Ilegal in Oaxaca City. It’s the launch party for the 2023 Bar Ilegal Tour, with the mezcal brand celebrating two decades of history in its original home, Café No Sé in Antigua, Guatemala. SUSU will bring the party, Ilegal will bring the drinks and tattoo artists will be busy buzzing free tats in the back during the course of a three-country, eight-stop tour between April and December.

An Illegal Mezcal

Ilegal made its unofficial – and well, illegal – debut when founder John Rexer began bussing crates of mezcal he sourced from Oaxaca to his new bar in Antigua more than 20 years ago. “Mezcal wasn’t exported legally to Guatemala at the time, so he started smuggling it in,” Gilbert Marquez, Ilegal’s global ambassador, says. “John has gotten into a lot of, you could say, sticky situations.”

By showcasing his wares at Café No Sé, Rexer gained access to an in-house focus group of consumers that helped him refine what he was looking for from his mezcal. Ilegal made a more formal debut by 2004 and is now one of the largest mezcal brands in the world. Bacardi acquired a minority stake in 2017, and in 2022, Ilegal sold approximately 220,000 cases across several dozen international markets.

Ilegal is working on doubling that sales figure pronto, and as such, Mal de Amor is bustling with activity during our visit. Much like roadwork in Pittsburgh, construction at the palenque is essentially year round at this point. Mal de Amor, run by fourth-generation mezcaleros Armando and Alvaro Hernández, practices artisanal (artesanal en Español) mezcal production, and the ongoing work brings in a constant influx of the equipment they need in the form of stills, fermenters and tahonas – the traditional method for crushing agave piñas with an enormous stone wheel pulled by horses or donkeys.

The palenque pit roasts agave using a combination of encino and mesquite wood, crushes agave via animal-powered tahona and uses open-air wooden fermenters. They practice double distillation with dozens of 250-liter copper pot stills heated with wooden logs via direct flame, with the first distillation run performed with the agave fibers kept in the juice. They also produce their own labels of mezcal, though about 80% of their production goes to Ilegal; the two entities have a partnership, with Ilegal investing in the palenque’s expansion and using the facility as its brand home. They’re committed to growing together and prioritizing job creation over automation, all the way down to the one-by-one bottling efforts by a crack team of employees.

Finding Mezcal Along One of Mexico’s Most Notorious Roads

How one writer discovered some of Oaxaca’s best mezcal producers on a stretch of steep, winding highwayAuthenticity, Tradition and Risk

In addition to its Joven, Ilegal produces Reposado and Añejo mezcal, something which some purists turn their noses up at, believing that authentic or traditional mezcal is never barrel-aged. “Well that depends on when folks think ‘tradition’ starts; mezcal has been aged in Mexico since before Mexico was a country,” Marquez says.

Marquez acknowledges that less than 5% of mezcal is matured in oak casks, so it’s far from the standard approach, but notes that certain sub-regions within Oaxaca and other mezcal-producing areas may be more likely to pursue the method than others. As Ilegal looks to expand its presence within Mexico, their barrel-aged mezcals are appealing to consumers who either have an affinity for other barrel-aged spirits, such as American whiskey, or are looking for a change of pace from the abundance of clear, unaged mezcal available to them.

More importantly, Marquez emphasizes that Ilegal isn’t attempting to showcase a singular or superior style of production, but is rather pursuing its own preference. “There’s an over-specification of what mezcal should or shouldn’t be,” he says. “It’s an artisanal spirit, so who is one artisan to say to another that your art form isn’t correct? It doesn’t mean it’s the best way or the only way, it’s the way we do it.”

One of the most cherished elements of mezcal is the spirit’s great breadth in terms of flavors and styles, with hundreds of agave varieties, micro-terroir and climate differences leading to massive changes in outcomes. Not to mention the specific methodologies that vary from village to village and family to family. “Mezcal is the most diverse spirit in the world,” Marquez says.

Yet, that beloved, diverse spirit is facing a serious threat in the form of its own success, with industrialization imperiling the long-term wellbeing and viability of the category. The irony of diversity falling way to homogenization in the pursuit of profits, and the resulting risk that creates, isn’t lost on those in the industry.

“I don’t want to be dramatic, but we don’t have much time,” says Vicente Reyes, a long-time advocate for the mezcal industry. He’s the founder of Hermano Maguey, a community development project which helps indigenous Oaxacan families while striving to make mezcal more sustainable, not only for the environment, but for people as well. “It’s getting late. Disaster is imminent, especially with the growth we’re having.”

Espadín is mezcal’s cash crop for several reasons, including a rapid six-to-eight year maturation period and a sugar-rich makeup that requires the lowest ratio of raw material required per liter of production. But massive monoculture fields, as opposed to wild harvesting varieties when and where they naturally occur, set a dangerous course for sustainability. Meanwhile, distilling byproducts are being dumped into water sources and harming the surrounding environment at the same time.

Reyes calls for the largest brands to put their money where their mouth is, for once. “That’s a ticket they have to pay,” he says. “What I haven’t seen yet is the willingness to do something impactful. I think they’re very naive. The way I see it is, if you have a big business, you have a big responsibility.”

Small family producers are squeezed out of the regulatory processes they’re then forced to abide by, and while large conglomerates invest billions into the business while extracting each dollar they earn and then some, those same producers are often benefiting the least in terms of monetary gain from all of this growth. “You cannot make a change without the commitment of the communities, you have to not try to convince them but instead co-create with them,” Reyes says.

The body that should, in theory, be most involved with the protection of the interests of its own producers and long-term future is the Consejo Regulador Del Mezcal, or CRM. Say those letters around most of the people with their boots in the fields, and it turns from an acronym into an epithet. “It’s become an entity that’s only concerned with growth and marketing,” Reyes says. “It’s always been a disaster because it’s too political. It should be an NGO. Their agenda is not clear to me.”

That doesn’t mean you should stop buying mezcal. To the contrary, actually. But you can make informed purchasing decisions about which brands you’re supporting and why. Are they following sustainable practices in the harvesting and cultivation of their agave? Are they investing into their producers and communities? Are they adhering to traditional rather than industrialized distillation?

Exploring the Community of Mezcal in Oaxaca City

You could spend weeks in Oaxaca and barely scratch the surface of the mezcal-soaked region. There’s as much to learn and explore as you’re willing to handle, and while you should head out into the fields and visit as many palenques as you can, you’ll also cover a lot of ground right in the city center.

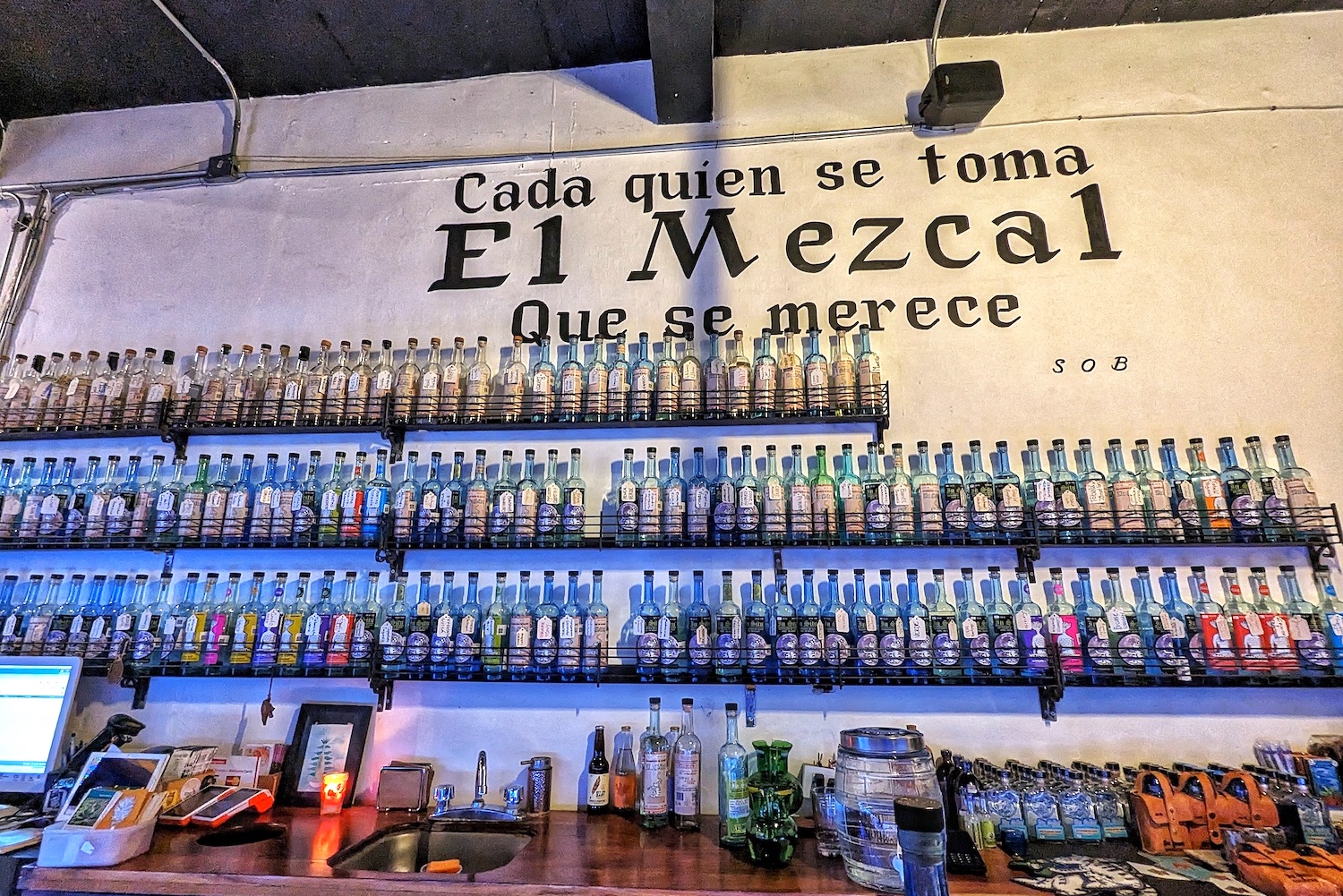

There are dozens of mezcalerías in Oaxaca City, many of them serving as both bar and bottle shop, some showcasing spirits they produce themselves, and others labels that they source straight from small producers you’d never be able to track down on your own. They’re all well accustomed to the tourists coming through town, which has increased from a trickle to a torrent in recent years.

You’ll need to make a reservation for Mezcaloteca, where you can sit down for a hosted, educational flight of between three and five mezcals lasting about an hour. At Mezcalería Cuish, the eponymous variety (also known as karwinskii) is highlighted alongside subspecies such as tobasiche and madrecuishe. Other wild harvested varieties are sold as well, including one of my favorites, tepeztate, which takes between 25 and 30 years to come of age, about four times as long as espadín.

El Cortijo Mezcalería showcases a deep selection of agave varieties and allows you to build themed tasting flights from their current lineup. There I enjoyed sampling selections such as jabalí and penca verde while chatting with a bartender who patiently endured my awful seventh-grade Spanish. Selva, meanwhile, is Oaxaca City’s best cocktail bar and one that has begun receiving international acclaim. High-concept drinks showcase a bounty of the region’s ingredients, bringing local flavors to the forefront in inventive creations.

Mezcalería In Situ showcases dozens of house labels, separated on its menu by production style, with sections devoted to clay pot distillation versus copper pot stills, for example. After working through more than a few agave varieties I had never even heard of before, let alone sampled, the bartender smiled knowingly and said, “Welcome to In Situ.”

It’s at In Situ that I had my meeting with Reyes. The staunchest of grassroots advocates for the industry was once on the other side of the fence, stoking the fires for some of the initial bursts of momentum that the mezcal industry enjoyed. “I do have guilt about it, I don’t know how much I can clean my karma,” he says. “I have to be on the other side of the equation now. Yes, I’m doing it out of guilt.” Self-flagellating as Reyes may be, there’s no denying his heart is in the right place — in Oaxaca, amid the people.

The most intrinsic, fundamental truth about mezcal is that it’s defined by the place it comes from and those who make it. “Mezcal is so beautiful and cultural, and that’s always been one of the most important aspects of mezcal, the community,” Marquez says. “That’s what we fell in love with.”

Reyes wants to get the power and the profits back to the community and create a more circular and sustainable economy for producers. “For me, my purpose is to make a difference here in Oaxaca,” he says. “Everyone knows each other here. This is the essence of the industry.”

It’s about time you went down to Oaxaca and experienced that essence for yourself, isn’t it?

Every Thursday, our resident experts see to it that you’re up to date on the latest from the world of drinks. Trend reports, bottle reviews, cocktail recipes and more. Sign up for THE SPILL now.