When filmmaker Antonio Campos first approached the French team behind the Peabody Award-winning documentary The Staircase — which follows novelist Michael Peterson after his wife Kathleen is found dead at the bottom of a staircase in their home in 2001 and he’s charged with her murder — he was granted access to their old footage, notes and even some unused video. But according to a new Vanity Fair report, director Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, producer Allyson Luchak and others associated with the original Staircase are upset with the creative liberties taken by the HBO Max adaptation.

“We gave [Campos] all the access he wanted, and I really trusted the man,” de Lestrade told the publication. “So that’s why today I’m very uncomfortable, because I feel that I’ve been betrayed in a way.”

The main issue de Lestrade and his team have with the HBO series is the way it implies that the documentary crew tried to edit their film in a way that would help Peterson’s appeal. Most egregiously, “The Beating Heart,” the fifth episode of the remake which is slated to air this Wednesday, features several scenes implying that The Staircase editor Sophie Brunet (portrayed by Juliette Binoche) edited the original eight episodes of the docuseries while she was involved in a romantic relationship with Peterson.

In real life, Brunet did have a relationship with Peterson, but as Vanity Fair notes, “Brunet and Peterson did not begin corresponding until after she left the documentary as planned to edit another project, 2004’s Holy Lola. De Lestrade hadn’t expected The Staircase to yield so much footage; he wound up enlisting two other editors, Stevenson and Jean-Pierre Bloc, to cut what would end up being eight episodes total. (Years later, de Lestrade filmed an additional five episodes of The Staircase. Brunet edited all of them — the final three she says she edited after she and Peterson broke up.)”

“My relationship with Michael never affected my editing,” Brunet wrote in a statement. “I never, ever cut anything out that would be damaging for him. I have too big an opinion of my job to be even remotely tempted to do anything like that. And Jean would never let it happen anyway. It is his film and I respect that greatly. And again: I had absolutely no dog in the fight for the first eight episodes. As for the following ones, I think one can notice a great empathy for Michael’s family in them. But that was Jean’s point of view as well as mine. Whatever you think or believe about Michael, you can’t deny that the situation for his children was terrible and unfair. As for the last three episodes, I could not possibly be suspected of wanting to favor Michael, since we had broken up before I finished editing.”

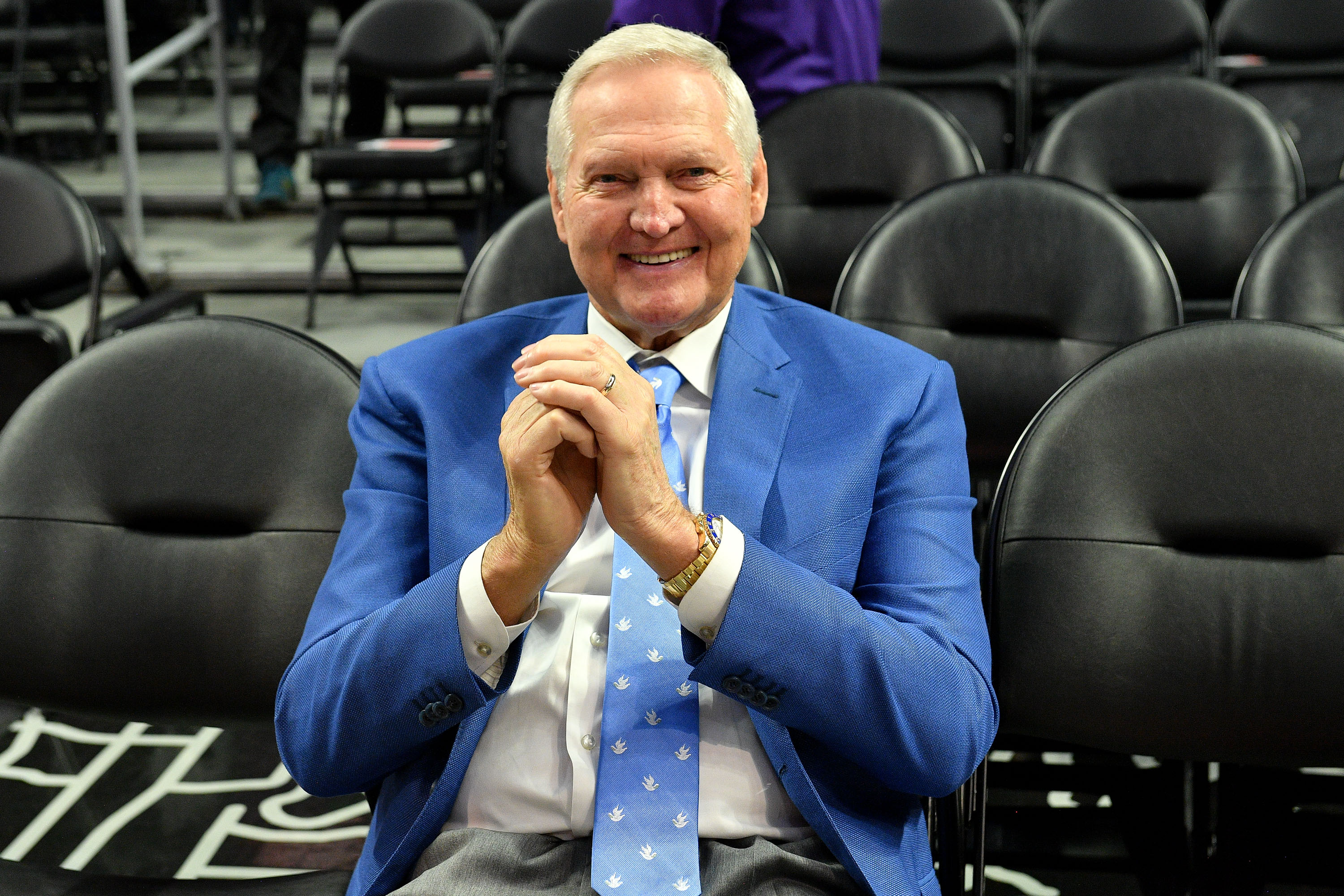

Of course, this isn’t the first HBO series to be called out for taking creative liberties. But the true-crime element does add an interesting wrinkle here; the real-life damage that bending the truth might cause here goes far beyond Jerry West getting upset over being portrayed as an asshole on Winning Time. The Staircase pulls heavily from the original docuseries — so heavily, in fact, that many courtroom scenes are lifted from the doc verbatim. That could lead viewers to believe that what they’re watching is all rooted in truth (or at least the version of the truth presented in the documentary). And while Jerry West’s life isn’t going to change dramatically because people might believe he once threw a trophy through his office window, de Lestrade’s might if people start to believe he edited his doc in a way that manipulated people into thinking Michael Peterson didn’t throw his wife down the stairs.

“I understand if you dramatize. But when you attack the credibility of my work, that’s really not acceptable to me,” de Lestrade said. “It’s alleged that we cut the documentary series in a way to help Peterson’s appeal, which is not true.” Even after all this time, the director says he remains undecided over whether Peterson is innocent or guity: “I can’t tell you if he had something to do with the death of Kathleen, because I don’t know.” (Peterson’s 2003 conviction was overturned in 2011 after it was revealed that Duane Deaver, an SBI analyst, falsely represented blood spatter evidence used against him, and he was granted a new trial. In 2017, he entered an Alford plea — a guilty plea in which the defendant still asserts their innocence but recognizes that sufficient evidence exists to convict them of the offense — on a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to time previously served.)

Because Peterson’s case is closed and he’s now a free man, there won’t be any legal ramifications for HBO’s inaccuracies in their adaptation of his story. But does that make them right?

“There’s a responsibility to fictionalize the truth accurately, because otherwise you’re adding another layer of confusion onto the case of the death of a woman,” Luchak told Vanity Fair. “I don’t know how that helps anybody.”

On Friday, de Lestrade sent a letter to Campos requesting that “the offending allegations be removed from episode five before it airs publicly” or that the show add a title card with a disclaimer to the beginning and ending of each episode reminding viewers that the series is a fictionalized version of events. Whether that’ll happen remains to be seen; we’ll have to tune in on Wednesday to find out.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.