Japan Railways is a stiff, buttoned-up organization. Its stations radiate the kind of bureaucratic seriousness required to run the world’s most reliable and orderly train service, and yet JR East won pop culture for a brief moment at the end of 2017 with its ski-season advertising campaign posters made in direct homage to the 1987 teen movie Take Me Out to the Snowland!. The film is a cinematic paean to the good old days of Japan’s Bubble Economy, akin to what John Hughes’s work represents to Americans. The reference to Snowland!, however, was not just a cheap dose of nostalgia for rich 50-somethings; it tapped into a recent longing and curiosity among Japanese youth about what it felt like to be alive during Japan’s big economic moment. For kids who’ve only known decades of economic malaise and monotonous consumer culture, the youth of the late 1980s seemed to have lived in a Golden Age, bouncing from trendy restaurants to discos in Armani and Chanel suits with yen notes streaming out the back of their German cars like confetti. So 30 years later, to boost their winter high-speed railway ticket sales, JR made a successful bet on the allure of Juppies.

Juppie, of course, is “Japanese Yuppie,” but before anyone gets the wrong idea, Juppie was never a standard term in Japanese. Neither The Official Yuppie Handbook’s Japanese translation in 1984, nor the 1987 men’s style book called Juppie: Can You Be an Adult? were particularly popular. Japanese media were grasping for a Yuppie-esque word in the early 1980s and landed on the buzzword shinjinrui — “new breed.” The idea here was that the materialist youth generation demonstrated an almost alien preference for leisure and consumption over the post-war ethos of hard work and organizational bonds. The characters in Take Me Out to the Snowland! were these New Breed Juppies, using their ample professional income to wallow in sophisticated culture, technological gadgets, and European import brands.

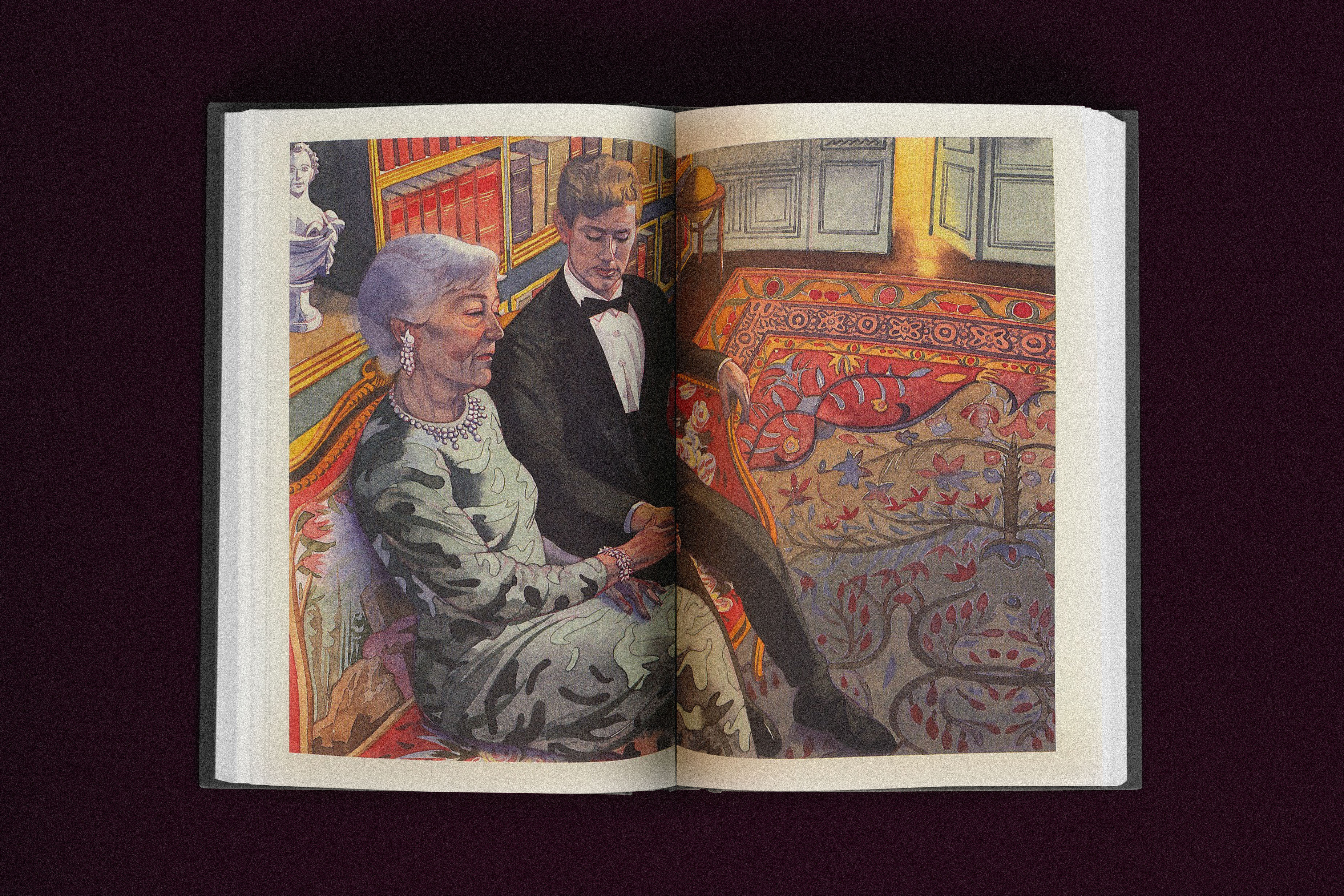

This is what makes Take Me Out to the Snowland! a useful introduction to the Juppie lifestyle. Compared to the wild antics of its American source material, Hot Dog…The Movie, Snowland! is painfully tame. The film opens as a native ad for the protagonist Fumio’s cherry-red Toyota Corolla II GP Turbo, which he outfits for backcountry skiing. On the car’s license plate is stamped “Shinagawa,” a class signifier only obtained when living near Tokyo’s toniest DMV office. Before launching out of his garage, Fumio pops in a city pop cassette and heads off to the upscale import supermarket Meidiya to pick up groceries. From there, Snowland! unfurls a loose semblance of a plot that primary serves as a vehicle to pitch viewers a catalog of high-end products: expensive boots, matching ski suits for him and her, flood-light backpacks for night skiing. An entire scene in a bar is built around showing off the latest in digital-sampling keyboards. No characters in the film have sex. Instead, their emotional climax involves conspicuous consumption and a self-sacrifice of dangerous night skiing to ensure that their trading-house employer can market a set of new products to the sporting press.

If American Yuppies were grown-up Preppies — the white-collar, paycheck-collecting culmination of a fancy education and cultural erudition — so too were the Juppies. Preppy culture was massive in Japan, a foundational aesthetic to the shinjinrui New Breed. In fact, it hit mass culture earlier than in the States.

A year before Lisa Birnbach’s The Official Preppy Handbook arrived on the New York Times best-seller list in 1980, Japan’s Men Club magazine ran a cover story called What is Preppie? breaking down East Coast prep style into a package of imitable looks. In the next few years, men and women hit Tokyo in matching Brooks Brothers oxford button-down shirts, khakis and Sperry’s boat shoes.

But the Preppy boom died a sudden death in 1983, when Juppies went way further into contemporary high-fashion trends than their American counterparts. With the successful Paris debut of Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons in 1981, Japanese youth culture abandoned American style and plunged into avant-garde and Continental sophistications. College students traded the ’50s teeny-bopper revival goods of their youth for difficult postmodernist philosophy. As the Japanese economy went into overdrive with the Plaza Accord of 1985, former Preppies with jobs took their fat bonuses and bought up Italian suits and asymmetrical black garments. Here arrived the archetypal Bubble Juppie, a clean-shaven Japanese man with moussed, techno-cut hair in a broad-shouldered suit jacket and Gucci loafers.

This, however, is where the similarities end. Both Yuppies and Juppies bowed down to the Gods of Consumerism, but American Yuppies emerged from an actual shift in the socioeconomic structure. In Reagan-era America, educated youth could make a lot more money than their parents — and not just in stolid fields like bond trading and corporate law, but also creative jobs such as graphic design and advertising copywriting. What emerged, without media direction, was a Yuppie “taste world” with its own unique wardrobes, leisure activities and morals. The Volvos, cross pens and squash rackets were not Madison Avenue-driven fads, but the behavioral residue of an actual lifestyle. The Official Yuppie Handbook perhaps spread Yuppie style beyond urban centers, but it codified, rather than invented, a pre-existing look.

In Japan, by comparison, the Bubble-era Juppies were ultimately kids pretending to be adults. They acquired their entire lifestyle by following the direction of manual-style consumer magazines to the letter. Each issue of Popeye or Hot Dog Press taught the aspiring Juppie where to shop, how to dress and which Italian restaurant should host their first date with an aspiring Juppie girlfriend. (Long-standing wage disparities between men and women in the Japanese labor market also made it more difficult for female Juppies to be the ones to pick up the bill.) American Yuppies were an organic, middle-brow diversion from mass culture; Juppies were mass culture. The result, as seen in Take Me to the Snowland!, was not a snobby rebellion, but a full embrace of the aspirational consumerist lifestyle dreamt up in the back offices of ad agencies. This is perhaps why the biggest contrast between the Yuppies and Juppies emerged back in their apartments. Yuppies read The New Yorker sitting on modernist furniture and eating a gourmet breakfast made with dozens of high-end appliances; the Juppies spent all their money on externally visible status signifiers like clothes, cars and parties, and lived like spartan college students at home.

The American socioeconomic structure that birthed Yuppies still exists today, which is why Yuppie culture has not as much disappeared as morphed into an amalgam of tech bros, Mayor Pete supporters and assorted creatives hungry for authentic, healthy, radically honest lives. The hierarchical pay scales at Japanese companies, on the other hand, provide just enough money for new employees to live in the company dorm. Juppie culture has only been possible in boom times; as soon as the Bubble Economy crashed in 1991, Juppie culture evaporated.

And before that, there was already a backlash. Hangers-on from the provinces read the same Juppie magazines and watered down the urbane vibe. The younger generation from Tokyo’s poshest suburbs rejected magazine-directed Juppie styles and returned to a looser American casual style called amekaji (and later, shibukaji). Meanwhile, the Japanese creative class splintered off and ushered in an edgier indie culture in the mid-1990s. A decade later, Bubble Juppie culture was relegated to a national joke — something like a painfully ugly living embodiment of the “Wham! Rap.”

At the same time, Japan never experienced a moral uprising against consumerism like we see in the Patrick Bateman Yuppie folk devil and the “Yuppie go home” Williamsburg anti-gentrification graffiti of the early aughts. The Juppies’ only crime in Japan was being caught indulging in outmoded aesthetics and superficial tastes. But with the contemporary revival of glossy city pop and Bubble nostalgia, their sentence has been commuted, with today’s economic anxiety making the Juppie star shine even brighter. When it’s foreign tourists, rather than Japanese youth, who do all the shopping in Tokyo’s once-vibrant Harajuku and Omotesando districts, there is a heroism in remembering how the Juppies once achieved so much self-definition and pleasure merely through buying things. Demonizing consumerism has always been a luxury of the privileged — some iterations of it, though, are more benign than others.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.