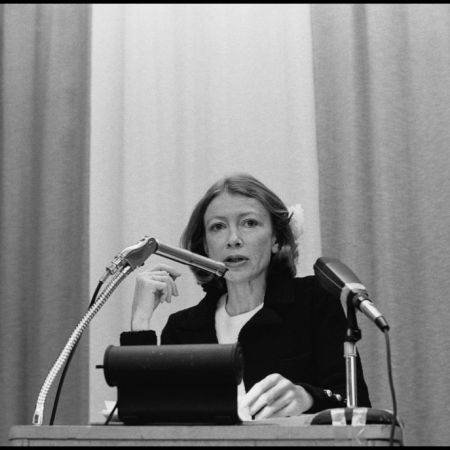

Few writers of her generation have had the impact on American culture that Joan Didion has had. Since Didion’s death in 2021, a host of writers have sought to reckon with her legacy, including Lili Anolik’s critically acclaimed Didion and Babitz, which contrasted Didion’s life and work with those of another literary figure inexorably entangled with Los Angeles.

In her new book We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine, New York Times film critic Alissa Wilkinson explored the breadth of Didion’s influence — on art, literature and politics. So far, the reviews have been enthusiastic, with Booklist‘s calling it “a cultural case study of the country Didion wrote about.”

“I’m hoping it’ll be illuminating for people who love Didion already, but also illuminating for people who don’t really care about Didion but are kind of interested in how we got to where we are,” Wilkinson explained in an interview with Variety. In this excerpt, Wilkinson zeroes in on Didion’s writing about one particular legal case and what it says about New York City, political careers and the dangers of nostalgia.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

That line was now over a decade old, and a lot had happened in the meantime. It was a sentence meant to explain a profoundly human behavior. In order to survive the chaos and randomness of the universe, we make up stories that explain why things happen, or give meaning to what ultimately has none. The baffling crime. The senseless war. The heart condition that comes out of nowhere. The murder in the family, the pointless drug addiction, the success that presents itself as a stroke of luck. Governments, too, make up stories for their citizens, a way to explain things to their people so they won’t get worried and dig into what’s really going on. Language can be as much a way to obscure reality as to reveal it, a phenomenon Didion had explored throughout the 1980s. The “Great Communicator” was telling stories from the Oval Office that were built as much or more on feeling as reality. And the country ate it up.

If Reagan did represent the fusion of Hollywood with Washington, what did that say about Hollywood? Was Hollywood a symptom of an American tendency — to rewrite stories, to construct heroes, to find a happy ending or at least an ending of some kind — or was it the reason for that tendency? Two or three generations into Hollywood history, what had it borne in Americans’ attitudes towards their own culture?

Didion detected in Americans not just the need to tell stories, but stories that tended towards that “pernicious nostalgia” that she found so rancid in 1988. She reused that same phrase — pernicious nostalgia — in perhaps her most famous essay for the NYRB: “Sentimental Journeys,” published in the January 17, 1991, issue.

The piece was ostensibly about the case of Trisha Meili, a young white professional woman who was jogging in Central Park on April 19, 1989, when she was viciously attacked, raped, and left in a critical state in the park by her attacker. She came to be known as the “Central Park Jogger.” Five Black and Latino teenagers were arrested and accused of perpetrating the crime, and later convicted and incarcerated. The city was fiercely preoccupied with the case, its tabloids and communities caught up in arguing about guilt and innocence. Real estate playboy Donald Trump took out a fulllength advertisement in the New York Times, calling for the five boys to be executed for their crimes. (They would be exonerated decades later on DNA evidence, with the real attacker identified; Trump would never admit he was wrong.)

But “Sentimental Journeys,” published after the verdicts were handed down, was not about the crime itself. Instead, Didion saw in the city’s reaction to the crime evidence that something in the culture had gone horribly sour — that a “pernicious nostalgia” had come to permeate the case.

Nostalgia: a wistful, sentimental, backwards casting of one’s gaze towards a prior era. There is a fondness in the look back that tends to paint the past as better than the present. And so, a pernicious nostalgia is one that has a corroding effect.

You could argue, easily, that Didion had been trafficking in some kind of nostalgia all her life. Her most famous works, essays like “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The White Album,” sketched a present in which meaning has ceased and sense has disappeared. She writes, often, about “no longer” understanding or believing that things happen for reasons of logic or purpose, about coming suddenly to believe that all narrative is sentimental. Yet she also loves the sentimental narrative, one in particular — the John Wayne character who tells the woman he loves that he’ll build her a house beyond the bend in the river. Is there anything more sentimental and nostalgic than that?

It’s probably true that Didion’s increasingly vocal assault on that pernicious nostalgia during the 1990s is partly a way of talking to herself. Just as in writing “The White Album” she mixed what was going on in the country’s breakdown with her own mental and physical breakdown, there’s a sense that her political and cultural writing near the end of the century — though almost always abstracted, with little to no sense of her personal state of mind revealed explicitly — is a way of sorting out what she feels now. She had never really proposed that the country go backwards, just that it had lost something it once had — but now she questioned those sentimental narratives. When she looked around her, she saw the effects of a culture that had become so accustomed to telling itself stories about a golden past and a present, one that looked like the movies, that it had forgotten how to face reality.

As an essay, “Sentimental Journeys” captures this sense. Crimes, she noted, were not all treated equally by the media or the citizens. Another crime, the murder of a Black woman, was virtually ignored by most people, a crime that was “expected” because the victim did not fit the mold that was relished by the era’s storytellers. “Crimes are universally understood to be news to the extent that they offer, however erroneously, a story, a lesson, a high concept,” she wrote.

But Tricia Meili — whom the media refused to name, a decision Didion wrote about in the essay with sharp skepticism — presented a different kind of victim, one that the city could latch onto as a representative archetype. News coverage tended to emphasize “perceived refinements of character and of manner and of taste,” which “tended to distort and to flatten, and ultimately to suggest not the actual victim of an actual crime but a fictional character of a slightly earlier period, the well-brought-up virgin who briefly graces the city with her presence and receives in turn a taste of ‘real life,’ ” she wrote.

What’s more, the victim seemed to have been conflated, by opinion writers and journalists and politicians and maybe even judges and juries, with the city itself. It was as if the crime committed against this young woman was committed against everyone, which of course meant that the young people presumed to have committed it — teenagers living in the projects, the youths who “menaced” the city — were representative of evil and all that threatened to bring the city down. This was an unbearably sentimental way to see things, Didion argued, just another story repeated in order to make reality, in which a woman was senselessly attacked at random, bearable. “It was precisely in the conflation of victim and city, this confusion of personal woe with public distress, that the crime’s ‘story’ would be found, its lesson, its encouraging promise of narrative resolution,” she wrote.

In writing “Sentimental Journeys,” Didion focuses narrowly on the culture of New York City, and what she termed its “preference for broad strokes.” There’s a kind of glittery sentimentality at New York’s core — “Lady Liberty, huddled masses, ticker-tape parades, heroes, gutters, bright lights, broken hearts, 8 million stories in the naked city” — that obscures the class conflicts and “arrangements” that widen the gap between the very rich and the very poor. Contrary to Reagan, the rising tide had not lifted all boats.

But what Didion was writing about, between the lines, is a much more general, more American problem. Sentimentality pops up everywhere else in the country, too. She had seen it in her travels. And in Hollywood, everyone was telling stories, no matter where they were: on a soundstage, at a dinner party, or in a boardroom. She’d seen how in South America, stories obscured reality; in the US, stories often obscured reality — and responsibility. New York’s narrative about itself was that it had a “dangerous but vital ‘energy’ ” and the Central Park Jogger case gave the city a place to focus its collective belief that the energy was threatened by “outsiders.”

New York’s politicians, sensing an opportunity, could use this narrative to performatively bolster their own positions. “The imposition of a sentimental, or false, narrative on the disparate and often random experience that constitutes the life of a city or a country means, necessarily, that much of what happens in that city or country will be rendered merely illustrative, a series of set pieces, or performance opportunities,” Didion wrote. For instance, both Mayor David Dinkins and Governor Mario Cuomo could make a show of being tough on crime by calling for an increased police presence on the streets. Would that have prevented the crime itself? Did it matter?

Joan Didion, Voice of a Generation and Beyond, Dies at 87 of Parkinson’s Disease

The enormously influential American author of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The Year of Magical Thinking” passed away ThursdayThe narrative, the story the city told itself to live, was obscuring what the true source of its sickness was. It was the same thing that had happened when the country tried to understand the youthful dropouts who had taken themselves to Haight-Ashbury decades before, or when Angelenos looked at unrest and bizarre crimes in their own city. It was what had happened in the West. “I started realizing there was a lot of ambiguity in the West’s belief that it had a stronghold on rugged individualism, since basically it was created by the federal government,” she told an interviewer in 1996.

The Central Park Jogger’s “story,” she wrote, was in search of “narrative resolution” — an echo of the kind of note you might receive from a studio executive while developing a project. The narrative was “about confrontation,” embodying “certain dramatic contrasts, or extremes” that New Yorkers believed unique to the setting in which they lived. The mayor and governor had seized upon “set pieces” or “performance opportunities,” like actors auditioning for their next role. (Indeed, Mario Cuomo had given a commanding performance at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, a speech so gripping that some declared him to be the Democrats’ answer to Reagan; he’d spend the years between 1988 and 1992 waffling on whether to run for president.)

The movie business had given the country patterns for understanding the world, stories to fit its reality into. When old stories went into reruns, new ones came to replace them. The whole country increasingly felt like one big movie set.

The above is excerpted from We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine by Alissa Wilkinson, published by Liveright Publishing Corporation on March 11, 2025.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.