I have to admit, the idea of using a precious weekend to visit a presidential library 100 miles north of New York City was not my idea of fun. That was before my wife mentioned the particulars: there was an exhibition celebrating the wartime friendship between FDR and Churchill, explored through top-secret communications, photos and artifacts.

When I mentioned this D-Day exhibit to my friends at Jaguar and suggested how without this successful trans-Atlantic camaraderie, the company might not exist, they offered me something fast and luxurious.

I was soon growling north in a “Firenze” red F-Pace SVR. My favorite Jaguar has always be the long-wheelbase version of the XJ8, which is no longer in production, but over the past several years, the people behind the leaping cat have slowly been returning to the days when people gasped at the sight of a Jag in their rearview mirror. The fastest cat I’d driven before the F-Pace was a 56 year-old E Type V12 convertible, which unfortunately required its owner to spend most of his time under it, rather than in it (though some people enjoy that sort of thing).

Once I cut free of the usual traffic that swarms the metro area bridges, even on Saturday morning, I was able to enjoy the nimble handling of an SUV with a 5.0-liter, supercharged V8 engine and top speed of 176 mph (apparently).

To be honest, I had never, ever felt I could personally enjoy the feeling of being in a small SUV. But the F-Pace forced me to rethink my phobia for the category, since the driving experience was more like that of a modern, paddle-shifting sports coupe — albeit one that can handle New York winters.

While the engine is one of the most aggressive I’ve ever driven in an SUV, there’s something refined and distinctly British about the F-Pace. Other drivers stare as they attempt to reconcile the elegant musculature with fat racing tires and quad aluminum exhaust pipes which lurk in the bumper, spitting and popping like base muffler porn for anyone who gets excited by torque and low-friction roller bearings. But despite the car’s ferocious power, it’s a charming family car at heart, with enough luxury and grace to add a veneer of sensibility to the monster that lurks under the hood.

It was, of course a different kind of monster that stalked Europe during the years of FDR’s unprecedented four-term reign as President of the United States. This special exhibition that ended this month, “D-Day: FDR and Churchill’s ‘Mighty Endeavor,” marked the 75th anniversary of the Allies’ greatest military achievement, the June 6, 1944, invasion of Normandy — code-named Operation OVERLORD.

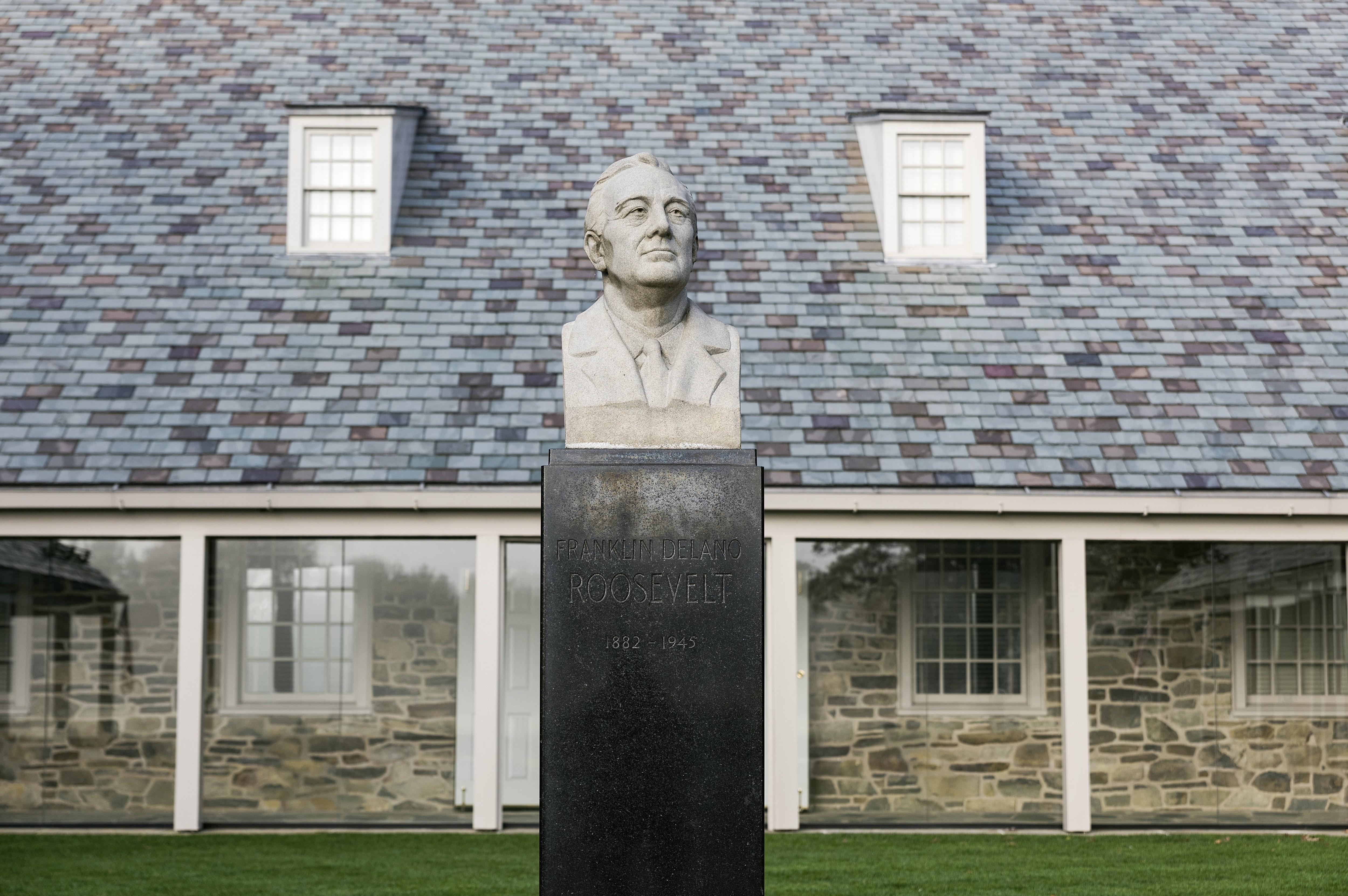

When we arrived at the FDR Library and Museum, located in Hyde Park, New York, I was surprised by how this is actually a museum on a fairly grand scale, not some reconditioned colonial mansion with a desk and a few dusty books and artifacts. It’s a facility that could almost certainly feature in a Top 10 of the country’s best museums; it not only serves the legacy of one of America’s most popular presidents, but also the idea of what it means to lead, inspire and heal a deeply wounded and broken nation — and one where thousands of people were suffering from widespread injustice, abuse and discrimination. And World War II hadn’t even started yet.

The permanent exhibits at the FDR Library & Museum demonstrate such intelligence and vision in how they’ve been curated that I soon understood why many visitors tackle this museum over two days. One can’t help but linger at every glass case, photograph, drinking cup or headphone station, each one capable of evoking a deep emotional response to what’s being presented.

From the scaffold props (intended to symbolize the burgeoning enthusiasm and physical rebuilding of a new America) to the meticulously reconstructed period kitchen and drawing room (where visitors can sit and listen to radio broadcasts as their grandparents once did), the FDR Library and Museum engages the emotions and the senses — not just the intellect.

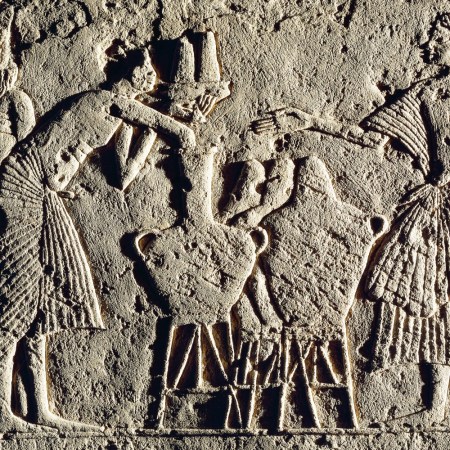

The Churchill/FDR exhibit told the story chronologically, starting with how the two men first met at the end of summer in secret, at sea, four months before the December 8th attack on Pearl Harbor. In August, 1941, however, the United States was not at war, and FDR faced fierce anti-war sentiment from Americans loath to be embroiled in yet another European conflict.

Little did they know what was coming. In fact, the time it took me to move through he exhibit, (which covers the years from 1941 to 1945) left me teary-eyed when I considered how in two hours, I had traveled across a landscape of interminable suffering. It reminded me of my late grandfather, who after agreeing to take me to a tank museum when I was a boy, locked himself in the bathroom and wouldn’t come out. And my wife’s grandfather, Purple Heart recipient Lt. Bert Knapp, a Jewish bombardier who was shot down over Nazi-occupied France and survived with the help of the Résistance.

While the term ‘friendship’ might seem too weak a subject to be explored in light of the brunt brutality that took place over those years, the exhibition makes it clear that a friendship was actually integral to the success of the Allied effort, as it helped both men cope with the massive emotional impact of sending thousands and thousands of fathers, husbands, brothers and sons into almost certain death. Further, when they faced scrutiny from their respective peers, Churchill and Roosevelt were able to console one another. Another concept implied by the exhibit, is how, while each leader represented his respective country, they also stood for something greater than statehood: the idea that human beings should live free. And despite the current political divides in America and the U.K., this remains an idea most people can agree on — even if they disagree on how to get there.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.