Most professional criminals do not hobnob with English royalty. But then, Arthur Barry was not most professional criminals. In his new book A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue, journalist Dean Jobb chronicles Barry’s complicated history and bold thefts — and, yes, a future King of England makes a memorable appearance.

Jobb’s nonfiction has chronicled numerous lives on the other side of the law, including his previous book, the critically acclaimed The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer. InsideHook spoke with Jobb about the enduring appeal of gentleman thieves, revisiting Jazz Age New York City and the way figures like Barry create their own mythology.

InsideHook: At the end of A Gentleman and a Thief, you mentioned that you had come across the subject of this book when you were researching con artists in early 20th-century New York. When did you first make that discovery? And at what point afterwards did you think this guy might be a good subject for a book?

Dean Jobb: My previous book was about a Victorian-era serial killer, Dr. Thomas Neal Cream. And the book before that was about a 1920s con artist from Chicago. So I was just thinking, what would I like to do next? I could use a change from a serial killer, which is pretty grim stuff. I just typed the words “1920s con artist” into Google just to see what would happen. Among the early hits was a link to the 1950s Life magazine article on Arthur Barry, describing him as the greatest jewel thief in history.

I’d never heard of this guy. And I thought, “This sounds intriguing.” The article was there in its full text. And by the time I’d read it, I had the outline of his story. I thought, “There’s something here, and I could really get interested in this guy.”

My next step was just to see how much was done. There was a biography he collaborated on in the early 1960s. But the more I read, the more I could see that there was a lot more I could potentially bring to the story, benefiting from the fact that he had given interviews for that book, interviews for Life and other magazines in the ’50s, and a lot of interviews back in the ’20s and ’30s in his heyday. Very early on, I realized — I hoped — that there was a book here.

Reading your book, I was surprised that there hadn’t been more written about Arthur Barry — to say nothing of a movie or a TV show about his life. As you say, he falls into this tradition of gentlemen thieves which have a longstanding appeal in pop culture.

He comes out of that Lupin tradition; also Arthur Raffles, who was a character who was invented by the brother-in-law of Arthur Conan Doyle, a man named E. W. Hornung, who in the early 1900s was immensely popular — and was so well known in Barry’s time that Barry was referred to in headlines as “the American Raffles.”

As for Barry’s story, it reads to me like whoever wrote the script for To Catch a Thief in the ’50s — the Hitchcock film with Cary Grant as a gentleman jewel thief — could have easily modeled it on Barry. Barry did get his 15 minutes of fame later in his life when the book came out. He was on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and a young Mike Wallace interviewed him, but there never seemed to be that leap to Hollywood.

Some of the more unexpected details were very revealing, too. The fact that the first thing he did when he broke out of prison was to reconnect with his wife and go on the lam with her — but also the way that he confessed to everything in order to protect her. He seems to have had something of a moral core, even if it didn’t stop him from stealing very expensive jewelry.

He was known as a gentlemanly thief because he behaved like a gentleman. If he broke into a bedroom and woke up the occupants, he would immediately try to put them at ease: “I’m only here to get the jewels; I won’t hurt anyone.” He’d even make small talk. He asked one couple, “How was the opera?” which had the sinister overtone that he’d been watching the house and seen that they were out for the night, but he tried to calm them down and even gave back a few valuable rings that that one socialite said were heirlooms.

She later told the press, “I know he’s terrible, but isn’t he charming?” He had that surface and then that M.O. of a gentlemanly thief, but I do think there was a good man in there, and I hope readers will look for that and see that he had a troubled childhood. That’s not because of his family; he was in what seems to have been a loving Irish working-class family in Worcester, Massachusetts. He became a bad boy, a juvenile delinquent, including some vandalism.

He went overseas during the Great War, and distinguished himself as a battlefield medic who was wounded — gassed — and was recommended for a medal for bravery for bringing wounded men off the battlefield. But then when he got back to New York after the war in a late wave of returning veterans, he couldn’t find a job. As he describes it he basically went through his options, would he be a bank robber? No; there were too many accomplices, and he didn’t want to be waving guns around. He even thought it was impolite to mug people on the street, and less impolite to try to sneak into their houses.

Initially he didn’t encounter any of his victims. He would time his break-ins to while they were at dinner downstairs or out for the night. He’d sneak in, sneak out and not encounter anyone. He even chose his criminal profession with an eye to being gallant and polite.

He was almost his own worst enemy at times. The medal he was recommended for was lost because he went AWOL after he got out of a hospital in Paris, decided he’d rather see Paris’s nightlife than line up for a medal and somehow in the fog of war simply rejoined his unit. Nobody seemed to notice he’d been gone.

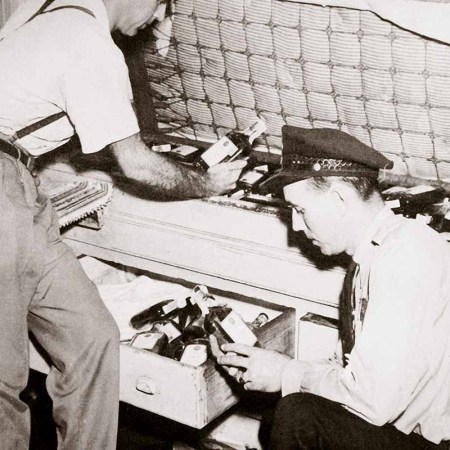

Did you know from the outset that Barry was originally a suspect in the Lindbergh kidnapping? That part definitely took me by surprise.

Early on, I discovered that. I can’t remember now if it was in the Life magazine feature. My first step was to gather any kind of in-depth story or feature done on him. As you go back in time, you see a lot of mythology, you see a lot of embellishment, which is why I prefer to go with what was said at the time as the best evidence.

There’s a famous photograph of him in a Newark jail being questioned about the Lindbergh kidnapping. And he’s with one of the chief witnesses, Dr. John Condon, who actually delivered the ransom to what’s believed to have been the kidnapper, and who exonerated Barry.

One of the things that really resonated for me was how his career really mirrored the times. He was a fast-living Broadway fixture and gambler. One of the reasons he had to steal so many jewels was because he blew his money as quickly as he stole it. Hee went from that high living to behind bars or on the lam for a number of years. And that perfectly mirrored what was going on in America after that. His career crashed just before the great crash of the stock market. And by the 1930s, he’s looked at as someone capable of being the most heinous criminal in the United States. It’s a long way for his reputation to fall.

What do you think it is about the idea of the gentleman thief that — whether they’re fiction or nonfiction — people find them so compelling then and now?

There is the audacity, I think, and the image that we get of the sophisticated criminal: Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief or David Niven, who played Raffles in an early movie. And also the panache; that’s one of the reasons I was drawn to Barry. He wasn’t a con artist per se, but he did things con artists do. He put on a tux and crashed Long Island parties where he mingled with the crowd and seemed to fit in. But his real purpose was to sneak upstairs at some point, case the joint so he could come back later and figure out where he was likely to find the jewels.

He took on a different persona like a con man would. And he’s something of an anti-hero. This was the way he rationalized it: any woman who can wear hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry knows where her next meal’s coming from. They’re also likely to be insured. And he avoided violence. I mean, there’s a threat inherent in someone breaking into the sanctity of your home, but he never hurt a victim and he never shot anyone.

He occupies a space where he’s a criminal, but if there’s a continuum of criminals he’s on the Robin Hood end of the spectrum. It is important to remember that while he was called a Robin Hood at times in the press, he stole from the rich and gave to himself. He wasn’t doing anything noble here. I think that’s that fascination that he can, as someone like this, pull it off. And especially on people who should know better where he could pass himself off as some rich trust fund kid in 1920s Long Island.

There’s a great scene in The Great Gatsby where Nick Carraway is encountering all these people that are at this big party at Gatsby’s and none of them know the host, none of them seem to know how they got there. They’re just hangers on, and that’s a world that he could just slip right into.

There’s something really amazing about how a working class guy from Massachusetts was, at one point, hanging out with the future king of England.

It was an amazing story. I had to open with that. And, yeah, the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, was vacationing on Long Island. It wasn’t an official royal visit, but he was in the media spotlight all the time. The wealthy of Long Island opened their mansions to him. One industrialist even gave him his entire estate to be his little vacation pad. Barry was casing the joint of a tycoon from Oklahoma named Joshua Cosden ran into the prince and was introduced to him. And that set off a clandestine nighttime tour of some of the nightclubs and speakeasies of Broadway with Barry under an assumed name as tour guide and the Prince of Wales and his entourage along for the ride.

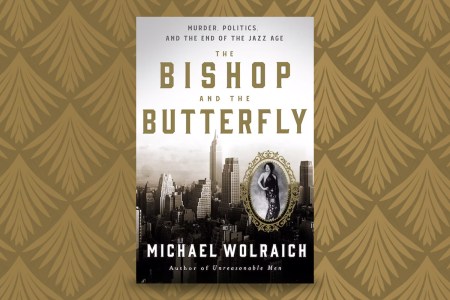

The Jazz-Age Murder That Transformed New York City

Michael Wolraich talks about unearthing the mysteries of “The Bishop and the Butterfly,” a tale which involves FDR during his time as governorThe heyday of Barry’s career was during Prohibition and — as you mention in the book — law enforcement had something of a selective approach to certain things at the time. Do you think that Barry was able to be as successful as he was if he’d been operating 10 years earlier or later?

Your question gets to the tenor of the times. There was an insidious blowback from Prohibition in that it made normally law-abiding citizens, anyone who just wanted to drink and maybe didn’t agree with the temperance movement, into criminals. And I do think that that changed people’s attitudes in the same way that there was a different feeling about bank robbers in the 1930s when the banks were seen as almost a worse threat than bank robbers.

But Barry was so interesting because I don’t think he could have existed as he did earlier or later because he was such a creature of Jazz Age New York. And as you mentioned, Prohibition was so laxly enforced and so flouted that the number of speakeasies and illegal bars in New York was over 30,000, and it had been only a few thousand legal ones before Prohibition.

The mayor of Berlin was visiting and talking to Jimmy Walker, New York City’s mayor, who himself really liked the nightclubs and speakeasies of New York. And Berlin’s mayor looked around at all the speakeasies and nightclubs and asked straight-faced, “Well, when does Prohibition come into effect?” And this was five or six years after Prohibition came into effect.

It was that kind of a time. Anything goes, live for the moment. A generation that had endured the war, survived a pandemic. I mean, Barry almost died in the war. So there was a sense that you should live it up. Barry just found a way to finance his roaring ’20s lifestyle. He could have gambled on the stock market like other people. He just gambled that he could get in and out of houses without getting shot or arrested.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.