The idea that a TV show needn’t fit squarely within a single genre is, of course, not exactly an earth-shattering concept. In fact, all the best dramas have been relying on humor to cut the tension for years now, be it the one-liners that endeared a bunch of vicious mobsters to us on The Sopranos or Peggy Olson deflecting a drunk and moody Don Draper by awkwardly yelling “PIZZA HOUSE” into the phone on Mad Men. Even more recently, we shudder to think what Succession would be without the hilariously inept Cousin Greg and the many, many insults hurled his way.

But while incorporating a little comic relief into a largely dramatic series is natural — and arguably necessary to keep things from getting too overwhelmingly heavy — working dark moments into a comedy can be much trickier. If the goal, ultimately, is to make people laugh, you have to know that certain subjects and scenarios are inherently risky; you can only bum an audience out so much before you lose them entirely. That’s why, on paper at least, HBO’s Barry should have never worked.

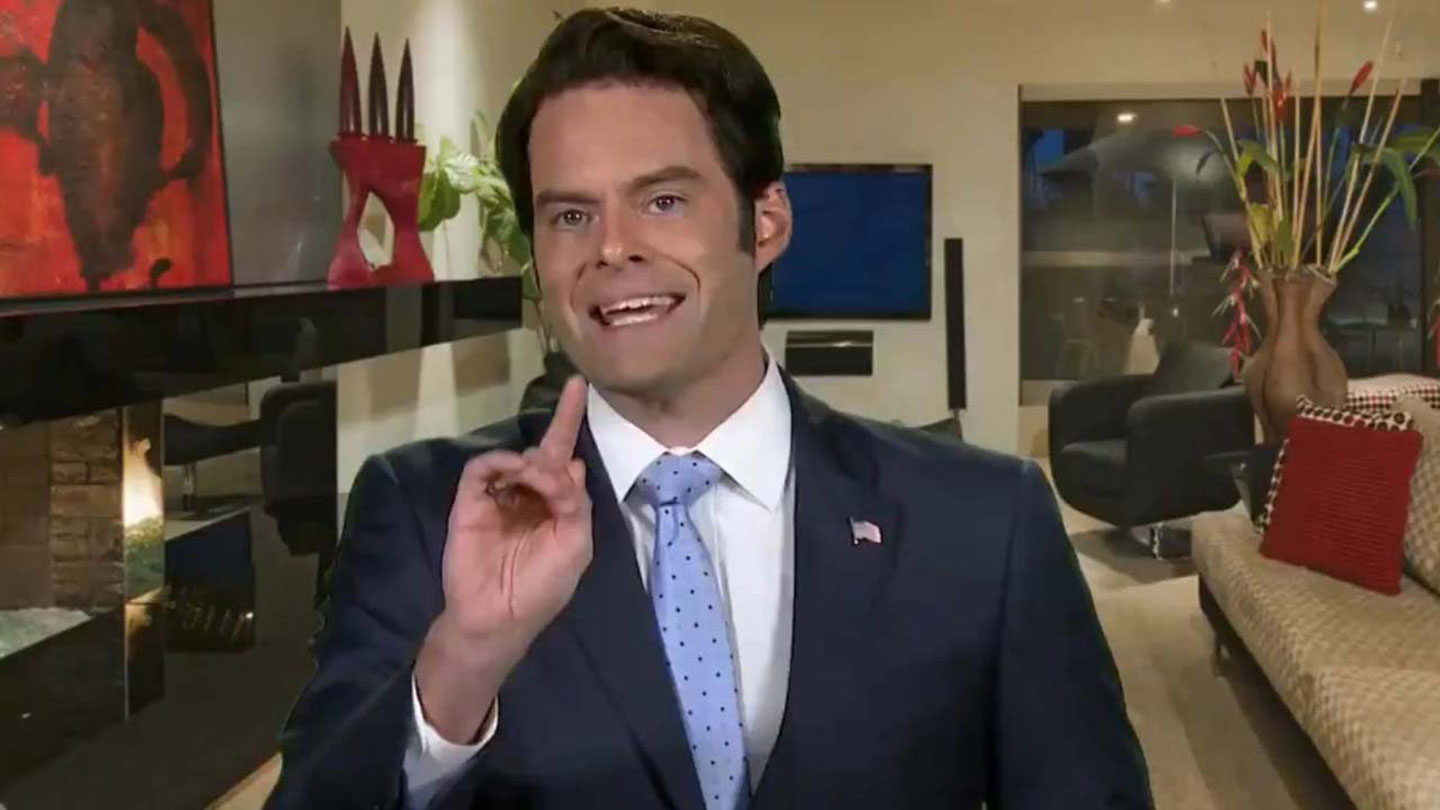

Since it first premiered back in 2018, the show (which finally returned on Sunday night after a three-year COVID-induced hiatus) has managed to pull off an impressive high-wire act, shifting tone in a way no other series on television can. Its premise — a hitman played by Bill Hader starts taking acting classes in an attempt to shift careers — is one that, by definition, can only be funny for so long; eventually, Barry’s past will of course catch up with him as he pursues a craft that will ideally thrust him into the spotlight, and when it does, it won’t be pretty.

For three seasons now, the writers on Barry have repeatedly painted themselves into corners and then inexplicably, impressively managed to escape. It’s as if they know they’re working on borrowed time. At some point, our surprisingly likable protagonist’s many, many crimes are going to catch up with him in one way or another and his world will come crashing down. Maybe the detectives investigating the stash-house massacre he perpetrated at the end of last season will eventually figure out his connection to the case. (After all, he was already found out once; it was pure luck that the detective who figured out Barry was responsible for Detective Moss’s murder at the end of season one ultimately decided to use that information to blackmail him into killing his ex-wife’s new boyfriend.) Maybe the Chechen mobsters he’s been working for will decide he’s too much of a liability and hire someone else to eliminate him. Maybe his self-absorbed girlfriend Sally, whose acting career is finally taking off as she shoots a TV show based on an inaccurate version of her own real-life trauma, will finally figure out the truth about him. No matter how it happens, Barry seems destined for a fall — his sins are too heinous for any kind of happy ending to feel feasible — and that’s a decidedly grim reality that no other comedy on TV has had to grapple with.

Barry has never shied away from the darkness inherent in its premise. The murders are gory and plentiful, and the flashbacks we get to Barry’s time in the Army reveal the wartime horrors he had to endure. (It’s obvious Barry’s suffering from some form of PTSD, which perhaps explains — though of course, doesn’t excuse — his initial decision to go into the murder-for-hire business.) In the first two seasons, we’ve seen he’s willing to take out just about anyone to avoid being found out; we’ve watched him kill his old Army buddy Chris and the girlfriend of his beloved acting mentor for knowing too much. There’s no glossing over the fact that Barry, by the very nature of what he does for a living, can never truly get close to anyone.

And yet, somehow, season 3 feels like the darkest the show has ever gone. It opens with a numb, aimless Barry preparing to torture and kill a man on behalf of a client, before the guy who hired him to get rid of the man who slept with his wife has a change of heart, deciding at the last second that he has chosen forgiveness. What the poor sap doesn’t realize, of course, is that there’s no turning back in contract killing, and an exasperated Barry shoots and kills both men before walking back to his car. Somehow, of all the murders we’ve seen him commit, this is the one that feels most jarring. The victims are seemingly good guys who both made bad decisions but ultimately had chosen to absolve each other of their sins, and while there’s always the risk that one of them would eventually change his mind, go to the cops and admit what Barry was hired to do, killing them doesn’t feel totally necessary. Their murders are meant to illustrate just how far gone Barry is; he sees himself as irredeemable (perhaps accurately!) and realizes that in his line of work, forgiveness is impossible.

As the episode goes on, we see just how bleak Barry’s life has become since we last saw him. His work with the Chechens has dried up thanks to the stash-house incident, and he’s been forced to take “amateur” gigs; comparatively low-stakes stuff like jilted lovers hiring him off of Craigslist. He’s been hallucinating — or maybe fantasizing? — bullets going into foreheads during mundane conversations with Sally. His acting class, the one thing that gave him a sense of purpose and a path to a new life, has closed, and his teacher, Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler) knows that Barry is responsible for the murder of his girlfriend.

Sounds hilarious, right?

And yet, remarkably, through it all, Barry remains far funnier than it has any business being. NoHo Hank, the goofy Chechen mobster who employed Barry for the first two seasons, remains one of the goofiest characters on TV, and Sally’s foray into Hollywood offers some biting commentary about how ridiculous the industry can be. Even the show’s tensest moment thus far — Barry’s confrontation with a gun-wielding Cousineau, who tells his former student that he can either turn himself in to the police or die — is alleviated by a brilliant moment in which Cousineau’s gun (an old pistol that was gifted to him by Rip Torn) falls apart as he’s drawing it, the bullets inside it rolling across the room to Barry’s feet. (Winkler absolutely deserves an Emmy for the hilarious way he utters “Oh” as it happens.) Naturally, Barry overpowers him and gets ready to kill him, but he can’t bring himself to do it. After another dramatic moment in which Cousineau urges him to earn his forgiveness, Barry, crazed and at his wit’s end, comes up with a plan to do just that — presumably setting up the rest of the season’s action — but not before the writers fire off one last joke, as a smiling Barry pulls his gun on Cousineau once more and politely asks him to get back in the trunk of his car.

Eventually, there’ll come a time when Barry will have to shift fully over to the drama. But for now, it continues to masterfully toe to the line between genres against all odds. It’s one of the best shows on television, whether it’s making us laugh or horrifying us with grisly murders and moral failings; there’s no telling how long it’ll be able to keep it going, but we’ll absolutely keep tuning in to find out.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.