Sports narratives are excellent vehicles for something America loves more than winning: racial reconciliation stories. Largely designed as a salve for white guilt, these stories follow a familiar arc: a team of Black and white players share a uniform but little else; after some internal conflict, something like friendship is kindled; white players come to the defense of their Black teammates; they set aside their differences to bring home a championship; the story ends in victory.

The fantasy here is that sports is a level playing field where the structural forces of racism do not apply. On the field, it doesn’t matter where you come from or what you look like, but what you can do, how well you can do it and how badly you want to win. While true to an extent, it is wishful thinking to believe sports is devoid of politics, that the real word isn’t waiting on the sidelines, that oppressed players are not acutely aware of these facts on and off the field. In Our Team: The Epic Story of Four Men and the World Series the Changed Baseball, Luke Epplin does not gloss over the grim racial realities of mid-20th-century America as he rehashes a little-known story of baseball integration centered around the Cleveland Indians, their World Series run in 1948 and four key figures who made it all possible, including the second Black baseball player to cross the color line.

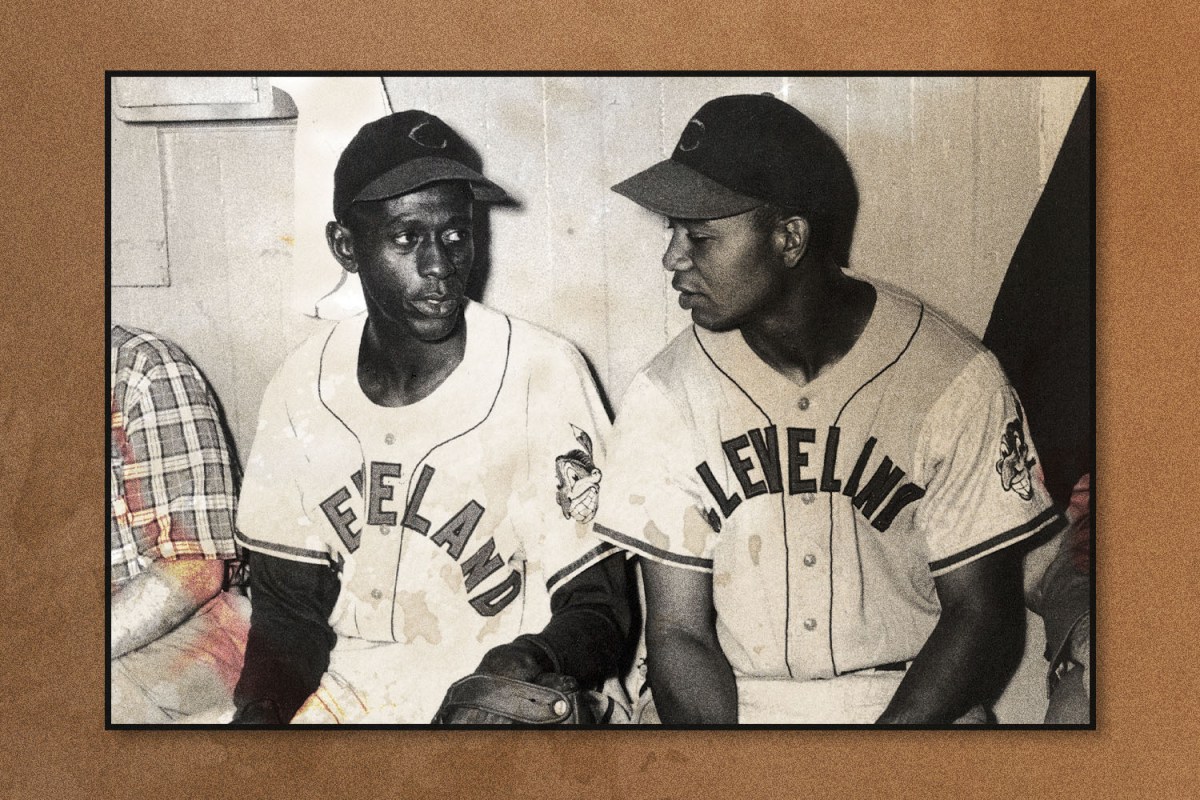

Though it’s been eclipsed by Jackie Robinson’s heroic journey into baseball lore, the story of Larry Doby is an equally fascinating one. Shy and introverted, Doby was a gifted athlete who excelled in both baseball and basketball. His athletic ability was so great that, upon joining the Indians, he learned a whole new position, transitioning from second base to right field and, later, center field, on account of his athleticism. During spring training, it became evident to management that no one on the team could throw farther, hit a ball harder or run faster than Doby. Despite his undeniable talent, Doby struggled on and off the field, battling loneliness, alienation, daily discrimination and extreme pressure to be exemplary in every way as a representative of all Black people. Doby felt if he made one misstep, the whole project of integration might falter.

Doby was recruited by Bill Veeck, the owner of the Cleveland Indians who lived and breathed baseball from the moment he could walk. Veeck was hellbent on winning a pennant, working tireless to do so, pushing through a devastating leg injury from WWII that required several amputations. With limited resources and no free agency at the time, he bet on the Negro Leagues as an alternative way to recruit more talent to push the Indians deeper into the postseason.

“I tried not to paint [Veeck] as a white savior,” Epplin told me. “I tried to paint him as someone who saw opportunity.” “He was practicing a form of 1940s moneyball. He needed to turn the Indians around really fast and he wanted to win a pennant right away. He recognized the way to do that was to sign the best players from the Negro Leagues.”

The other player Veeck signed was Satchel Paige, a legendary pitcher from the Negro Leagues who, at the age of 42, became the oldest rookie in the MLB. Paige was a serious boss on the mound known for his swagger, theatrical command of the audience and lightning-quick fastball that landed with a resounding wallop in the catcher’s mitt. Paige deserved to be in the majors from day one, and knew it. Whenever someone asked why he hadn’t made the leap to the majors, he replied wryly, “My price tag is too high.”

When he finally got his chance in 1948 (one year after Doby), he pulled out one of his old tricks, handing the catcher a folded up handkerchief and telling him to place the tiny square anywhere across home plate. Sure enough, Paige drilled home fastball after fastball right over the handkerchief.

Paige joined Bob Feller in the pitching rotation, a once beloved star rookie who had since soured in the eyes of fans frustrated by a team that repeatedly fell apart late in the season. Feller was a wholesome, milk-fed, homegrown hero hailing from Iowa. Alongside his father, he plowed a diamond of dirt from the cornfields of his family farm and there he trained, honing his rocket of an arm from a young age. Soon he earned county-wide recognition for his ferocious fastball and, eventually, attracted the eye of major league scouts. To many, he was the American Dream personified, and his life story elevated him to national fame, unlocking the hearts of fans across the country.

Feller was also a savvy entrepreneur who prefigured the modern-day athlete-businessman we’ve come to know so well today. Though he lost some of his prime pitching years while serving in WWII, after returning from overseas, he fashioned himself into a one-man enterprise hellbent on recovering whatever profits he could. To this end, he leveraged his own life story and celebrity into a radio show, syndicated newspaper column, memoir, and, biggest of all, a 1946 barnstorming campaign in which he organized exhibition games during the off season between white major leaguers and players from the Negro leagues.

Feller and Paige had crossed paths many times while barnstorming and cultivated a heated rivalry. “They’d dueled through a depression, then a war, and now into an era of tentative integration,” writes Epplin. The rivalry was fueled, in part, by race, something Feller essentially doubled down on just as integration was gaining a foothold. At a glance this looks like an obvious example of Feller exploiting Paige. This is true in some regards, but Paige was also using Feller to earn more money, and also to make a last ditch attempt at making the leap to the majors. They propped up one other, and it worked out for both.

Over several exhibition games and then a rematch, Paige proved to be the superior pitcher. Though he couldn’t throw as hard as he used to, Paige boasted more experience than any living pitcher and was a master of his craft, capable of outwitting his opponents and blowing them away with a fastball when needed. When one reporter suggested Paige stood a good chance to win Rookie of the Year, he responded, “You may be right, man, but 22 years is a long time to be a rookie.”

Epplin presents Feller and Paige as foils to one another, but he also points out that, “In an era when mainstream media hailed Feller as an avatar of archetypal American values, Paige embodied them equally, even if so much of white America remained oblivious to it.”

From the outset, I assumed Epplin had designs to tell a story larger than sports, a story that shed light on a historical moment or our national character. But Epplin threw me a curveball. There was some mythmaking, yes, but by and large Epplin resists the temptation to conflate a victory on the diamond with a victory in society — toward integration, racial reconciliation, overcoming poverty, whatever it may be.

“The racial reconciliation story is catnip,” Epplin told me. “It gives this pat way of showing how integration could happen almost seamlessly, but it just doesn’t happen like that.”

During the season, Doby faced endured racial slurs from fans, was routinely turned away by security at ballparks and often had to stay in a separate hotel from his white teammates. Even after winning the World Series in his second season (and Paige’s first) with Cleveland, “[Doby] comes back the hero, is paraded through his hometown of Paterson, [New Jersey], the mayor gives a speech about him, and then he tries to buy a house and he can’t do it,” says Epplin.

Epplin is as much a student of narrative as he is of baseball, and so too were his subjects. “Three of the four people [I wrote about] were masters of mythmaking,” said Epplin. “They didn’t even need the press for it. They just recognized the power of narrative and how it could help them get what they wanted,” he added, noting that, with the exception of shy Doby, each authored multiple autobiographies.

“Mythmaking was second nature to many sports writers,” writes Epplin, and these colorful anecdotes are one of the great joys of reading this book. Epplin emulates this mythic style to an extent, delivering punchy alliteration and personifying national attitudes into a single character, but he also exercises restraint, scaling down this story full of legends to a more human level. These men did great things, but at the end of the day they were still human, baseball was just a game, and structural racism could not be defeated on the diamond.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.