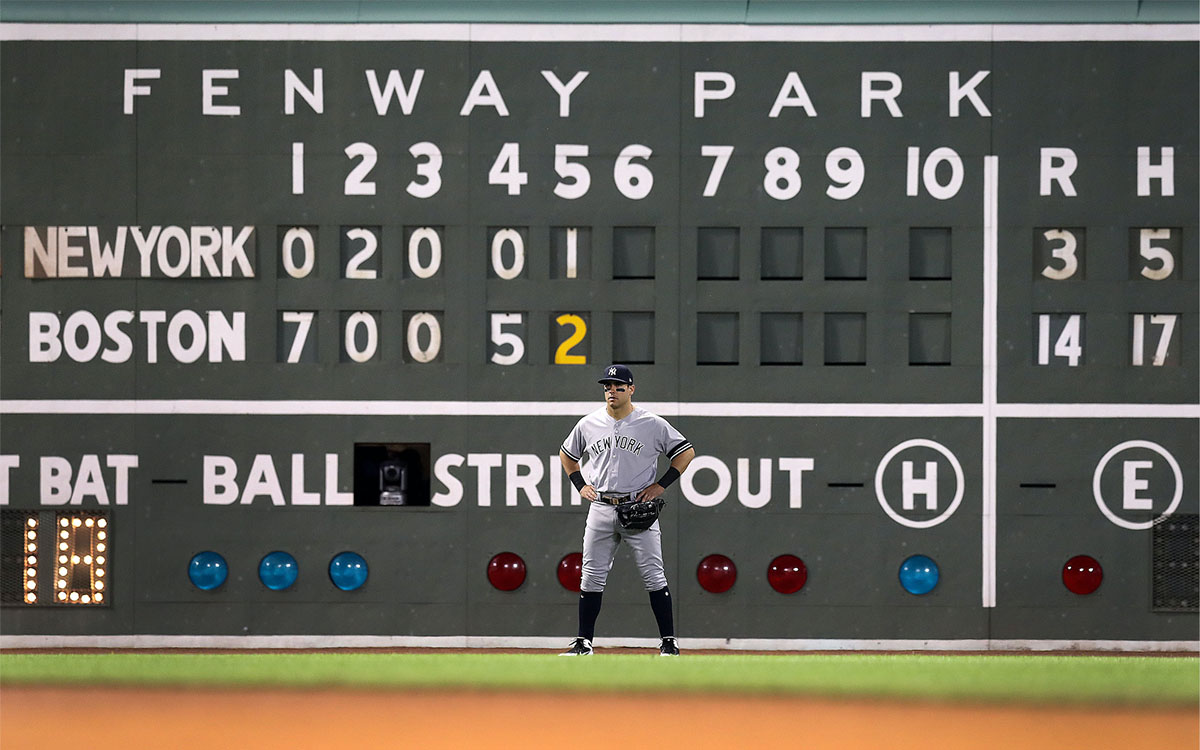

Last week, I watched the Yankees play the Indians at Yankee Stadium. It was, without question, the worst professional baseball game I have ever attended. That title used to belong to a 17-3 drubbing the Red Sox served the Yankees in the early 2000s (Red Sox fans took over the Stadium and started chanting “Yankees suck!”), but this experience beats that one, for a few reasons: A) I had work in the morning, B) I’d actually paid for my ticket, C) I had a long commute home and D) The Indians went up 7-0 in the first inning.

The 2019 New York Yankees can score, don’t get me wrong. Their run differential is +145, good for fourth best in the league, they’ve hit 229 home runs this year, good for second in the league, and they’re among the best in baseball at come-from-behind wins. MLB teams lose around two-thirds of games in which they don’t score the first run; the Yankees have remained over .500 all season in such games. That’s a big reason they’re currently fighting for the best overall record in MLB.

That said, seven runs in the first inning often sounds the death knell. The Indians went on to win 19-5, on 24 hits and seven home runs. The Yankees used five pitchers, scraped across a couple meaningless runs once the Indians marched out their lesser relievers, and maybe a couple dozen of the 44,654 in attendance stayed for the full three hours and 28 minutes. I left at the end of the seventh, without hearing “New York, New York” — which I can tell you feels far worse than hearing it after a 5-4 or 3-1 loss.

The day after the defeat, Aaron Boone made waves for suggesting that Major League Baseball look into implementing a mercy rule. In fairness, it makes for a funny headline. The “fully operational Death Star” New York Yankees feel brutalized by a 19-5 rout, and would rather it didn’t happen again. You don’t say.

But it wasn’t Boone’s pride that led him to make the comments. He’s from baseball royalty, probably the closest thing the sport has to the Manning family, and has been around the game his entire life. He’s seen his share of blowouts. Boone was actually concerned about player safety. One of the five pitchers the Yankees brought in to crawl their way to the bottom of the ninth was a kid named Mike Ford. Ford’s a first baseman, and has been filling in for injured Yankee starter Luke Voit. But due to a depleted bullpen, three more must-win games against the Indians, and Ford’s limited experience with pitching (he tossed games while at Princeton), he was pressed into duty.

It didn’t go too well. He got through two innings, but he gave up two home runs. And more importantly, he had to throw 42 pitches. Pitching is tough enough when you have five days to prepare for it. Many aging veterans (like C.C. Sabathia, a fellow Yankee) need six days of rest in order to have decent outings and make it through the season unscathed. It’s an unnatural motion, reaching back and slinging it as hard as you can over and over again, and there’s a reason the phrase “Tommy John” is as ubiquitous as “Cracker Jack” at a ballpark.

To be clear, Mike Ford is fine. He iced his shoulder after the game, and as he traditionally either DHs or plays first base, his arm should have a nice rest in store. But Boone also had a point when he said, “there might be some merit to exploring [a potential mercy rule in MLB].”

Position players are being called upon to pitch because they “once threw 90 in high school” at an alarming rate these days. In 2011, a position player pitched just eight times over the course of an entire season. In 2019, fans have seen it 78 times. That’s an 875% increase, and there’s still a quarter of the season to go.

Why is this happening? A few reasons. For starters, you might’ve heard that baseball players are hitting the ball out of the ballpark this year. In May, MLB players combined for 1,135 home runs, an all-time record for one month. Chalk it up to launch angle, chalk it up to a “juiced” ball (there have been accusations that MLB reduced the drag on its ball to ensure it travels farther) — whatever it is, the league is on a scoring tear. In fact, as of today, MLB has gone 37 straight days with at least one player posting a multi-home run game. The players are going to end up hitting 600 more home runs than the previous highest year, in 2017.

Home runs chase pitchers out of games. There is nothing more demoralizing than to watch a ball go over the fence, and once they unravel — walking batters, checking runners incessantly, feeling generally sorry for themselves — the manager goes to the bullpen. Bullpens are heftier these days, because they have to be. The heralded 200-innings mark, long held as a sign of a starting pitcher’s durability over the course of a season, is a dying statistic. While 39 pitchers reached it in 2011, only 13 reached it last year. That’s because relievers are shouldering more of the load; they’ve picked up an extra inning of slack over the last decade.

Bullpen arms can be extremely effective (just ask the Rays, who invented the nascent “opener” strategy), but they can also be erratic. And when they come into a game early, one that’s out of control or trending that way, it can get ugly.

Blowouts are also more common due to the state of the league today: there are several teams actively trying to not win games. Why? Because it works. Not so long ago the Houston Astros lost 100 games three years in a row. They stockpiled assets, freed up cap space, made a couple crucial trades, won the 2017 World Series, and last night opened against the Detroit Tigers as the heaviest favorite in a game in the last 15 seasons, at -500 (the Tigers won, 2-1, in an act of statistical defiance).

The Tigers, unsurprisingly, are working the Astros’ old strategy to a tee, and are on pace to lose 110 games this year. When you have teams unwilling to compete, and general managers feigning ignorance or hiding behind bogus “We’re a small market” declarations (small markets don’t exist in baseball; every team is owned by a billionaire; don’t let them trick you), you’re going to have games that unofficially end about an hour after fans sit in their seats.

But what if the last pitch of these games did, officially, arrive a bit earlier? Like I said, no self-respecting fan stayed to watch that Yankees-Indians game. When Boone floated his comments on the mercy rule, he mentioned that the 7th inning might make sense as a “cut-off” inning. This would square with Little League, where the mercy rule comes into effect whenever a team is trailing the other by at least 10 runs after four innings (Little League plays six innings total).

Let’s imagine an MLB game ends once the seventh inning finishes, because a team is down 10 runs. Last call on alcohol comes in the seventh inning, so anyone looking to drown their sorrows for the final two innings is out of luck. Concession stands are likely losing money at that point anyway, given the dwindling employee-to-patron ratio.

In-stadium revenue might be beside the point here, though. Millions more (if that) are watching at home, and those people are not hanging around to watch commercials. If I see that the Yankees are winning 13-2 in the 5th, I’m switching to Netflix.

And mathematically, the losing team is simply not going to come back and win that game. In the history of Major League Baseball, 218,973 games have been played. Only seven times, I repeat, SEVEN TIMES, has a team losing by 10 or more runs come back to win the game. Of those seven, only two comebacks occurred after the seventh inning — and one of the instances took place in 1925, when no one knew what a curveball was, so that one basically doesn’t count.

The point is, teams don’t win games when they give up a ton of runs really early. The rest of the game is a pointless charade: fans pretend they’re not furious they dished out a lot of money (or whoop for each unnecessary added run), position players who pitched in Little League start sweating bullets, managers rub their temples thinking about their depleted bullpens for the rest of the week, advertisers groan, and MLB sighs, realizing articles like this are sure to follow.

For a league so concerned about injuries, pace of play and parity, it makes sense to at least consider calling games that get out of hand. I wouldn’t recommend imposing a mercy rule for the playoffs (though, interestingly, no team has overcome even an eight-run deficit in the postseason), but why not give players rest on a day that they simply don’t have it? The season is grueling, and almost absurdly long by modern standards for professional sports. So a hitter is upset he can’t go 5-for-5? Get over it. An RSN’s official Chevrolet dealer is pissed it won’t have an audience for its 8th inning commercial? That spot wasn’t going to be seen anyway. Rain delays happen all the time. Advertisers live.

For now, this is a waiting game. Baseball took long enough to expand its rosters to 26 men (active for the 2020 season, and a direct result of larger bullpens), so something as seismic as a mercy rule will take significant time. Until that day comes, if it ever does, enjoy watching shortstops haplessly serve up meatballs while fans make for the exits. Just hope he can still sling it to first base the next evening.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=450%2C450)

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=750%2C500)