Paul Thomas Anderson has a type. That’s not in reference to Alana Haim, the star of his latest film Licorice Pizza, though she and her onscreen alter ego Alana Kane both fit snugly into a lineage of aloof Cali cool-girls to whom Anderson has gravitated in his work (Shasta Fay Hepworth of Inherent Vice could be her distant cousin) and life (there’s a direct line to be traced from Haim to fellow indie chanteuses like Anderson’s former collaborator Aimee Mann and very former lover Fiona Apple). And he does shoot her with more slackened-jaw admiration than anyone has ever applied to the subject of their lens, as if this film was nothing but a pretense to document what her face looks like from every conceivable angle, under every conceivable light. And maybe it’s worth noting that she has been cast as an effervescent crush magnet seemingly incapable of entering a room without inflaming the passions of anyone in her immediate vicinity.

But the most purely, classically Andersonian figure in Licorice Pizza is Gary Valentine, portrayed by Cooper Hoffman as an amalgam of key traits from the men who have led the director’s other films. Like Boogie Nights’ fresh-faced porn star Eddie “Dirk Diggler” Adams, Gary’s also a born hustler who won’t let being a teenager slow his grown-up work ethic — he’s cocksure, just without the use of his cock. A virgin hopeful about getting to second base, he’s halfway between Dirk’s sexual maturity and the precocity of quiz-show wunderkind Stanley Spector from Magnolia, sharing in the kid’s desire to be taken seriously despite his green age. He’s got the boundless ambition of Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood, albeit without the resentment for those standing in his way. In his all-id libidinousness, he’s an indirect descendant of Freddie Quell from The Master. Like Inherent Vice’s Doc Sportello, he’s hung up on the shimmering woman drifting elliptically in and out of his life, and like Phantom Thread’s Reynolds Woodcock, he spars with her when they’re together in their own playful-combative form of love. As with so many of these men, Gary has no relationship to speak of with his father.

The crucial difference between ruddy-cheeked Gary and his many forebears is that he’s a pretty happy person. He genuinely loves his life, and why shouldn’t he? He’s a high schooler with a solid income from acting gigs supplemented by get-rich-quick schemes hawking waterbeds or pinball machines, a thrilling level of agency that allows him to impress dates by paying for dinner at the now-defunct Los Angeles culinary institution Tail o’ the Cock. The days are long and the nights are warm; Anderson and his co-cinematographer Michael Bauman make every snapshot of summer ’73 look like perfection, the hazy light just clement enough to allow hours spent outside without the beading of sweat. With Gary’s head swimming in the intoxicating effects of pubescent infatuation, he does feel the intensity that Anderson has made his stock-in-trade. (Significantly, he and Alana often run into and out of their scenes at a breakneck sprint, like time isn’t happening fast enough for them.) It’s just that he’s unencumbered by the anxiety, paranoia, egomania, desperation or obsession that’s historically gone with it.

The inexorable bond between these two characters, more intimate than friendship and stopping just short of romance, allows Anderson to glide into a looser, kinder, altogether more chilled-out register still unmistakable as his own. Without sacrificing one iota of his towering ambition — the run time cracks the two-hour mark, and the script casually addresses the changing face of an America in flux — he shifts into a mode of good-times nostalgia befitting the genesis of the project. (The non-stop party of the ‘70s had yet to sour, its vibes harshed by the arrival of the ‘80s, as witnessed in Boogie Nights.) The script stitches together real-life Hollywood producer Gary Goetzmann’s recollections from his own younger years, explaining some of the film’s possibly discomfiting edges as tall-tale semi-fact. The tentative attraction between a 15-year-old like Gary and a fetching twentysomething like Alana, a polarizing running gag involving a white businessman speaking in a Japanese accent — if we find these alienating, it’s only because that’s how it happened, or how Goetzmann remembers it. The past is a foreign country, and the film recognizes that it’s not always a hospitable one.

As much as these were Gary’s salad days of chasing skirt and making dough, Alana wanders through this period with a deeper sense of searching isolation. She bounces from one man to the next looking for something she can’t name, trying to correct the mistakes of the last dalliance with the next. Though she suffers from the adolescent’s delusion that she already knows everything, she’s in want of some way to see and be part of a world she’s still figuring out, an impulse that melds her professional and romantic moves. As much as this is a double coming-of-age narrative, the arc of the film is one of calibration, as Alana tries on different personae to find one that fits.

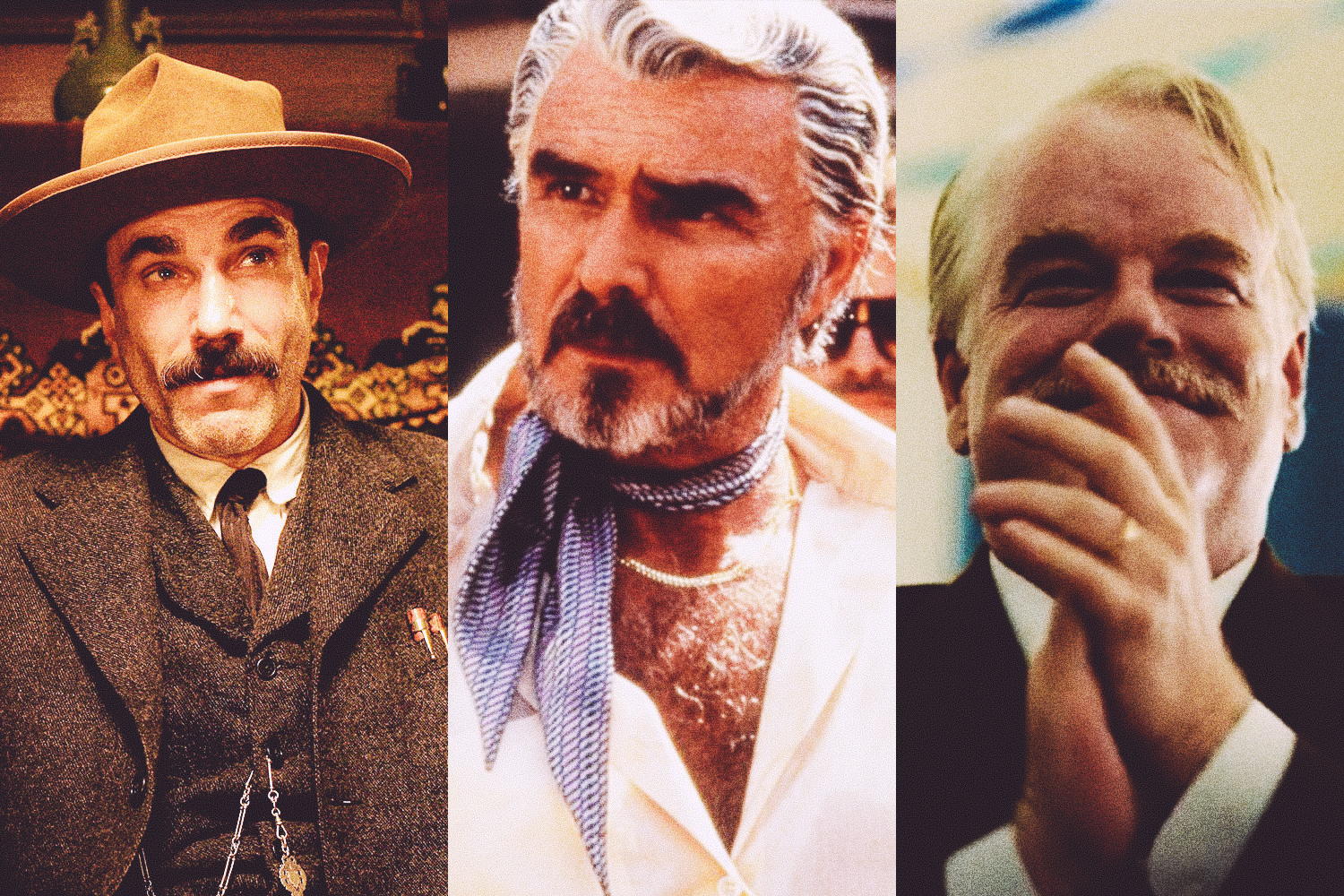

We meet her as an assistant to a school-portrait photographer who smacks her on the rump as she walks by him; naturally, she’s taken with Gary’s earnestness and innocence when the boy sidles up to her and starts spitting his endearingly transparent game. She’s impressed enough by his moderate success to accompany him on a work trip to New York, only to hop into the lap of Gary’s slightly-less-immature costar Lance when he flirts on the plane over. His small-fry stature eventually drives her to bona fide movie star Jack Holden (a soused Sean Penn, doing his best William Holden), until she realizes that the alcoholic narcissist lives in his own reality with little room for her. From there, she takes up with the campaign of fledgling politician Joel Wachs (Benny Safdie, one of PTA’s numerous pals filling out the cast) and responds to him as the one morally upstanding guy to cross her path, someone with a clear view of his route into the future. When what she misreads as a date turns into the discovery that he’s as lost and imperfect as anyone else, she’s shattered.

She punctuates each of these failed couplings by returning to Gary, the puppydog true north she comes to appreciate as consistent, harmless and sweet. It’s not that he doesn’t have flaws. The kid’s an incorrigible flirt, sometimes with other girls, and when he happens to be in Alana’s good graces, he always overplays his hand. Seconds after one of their reconciliations, Gary excitedly announces to a roomful of people that she’s going to be his wife, restarting their on-again-off-again cycle once more. They bicker constantly, and can only bear to admit how much they care for each other when one of them lands in a perilous situation like a wrongful murder accusation or a motorcycle stunt gone awry. But following his own example in Phantom Thread, Anderson recognizes that the perfect match comes down to compatibility in conflict, the stability of knowing how to navigate someone else’s combative tendencies rather than dull, stagnant peace.

In one key moment, Alana takes on a mother’s tenor as she warns an insouciant Gary not to drive away while she’s speaking to him, and later, she indignantly declares, “You’re talking about pinball machines. I’m a politician!” when merely volunteering for Wachs. Her weighing of the grown-up she’s slowly becoming against the remnants of her inner child drives the film, in one instance literally, as Alana steps up in a crisis and drifts a gas-less truck backwards through a hilly neighborhood. In this respect, she qualifies as the main character of the film, the first female protagonist in PTA’s oeuvre. His filmography is littered with authoritative, complex women — Boogie Nights’ Amber Waves, The Master’s Peggy Dodd, Phantom Thread’s Alma — but Alana’s the only one who commands the shape of the film in which she appears.

Her roundabout personal track dictates the episodic hangout format this film takes, the clearest sign of Anderson’s relaxed vibe. (As my colleague Tim Grierson has noted, switching from cocaine to marijuana may have something to do with this shift into a relatively chilled-out mode.) For followers of his career trajectory, it’s deeply rewarding to see someone whose work has always been marked by some inner torment taking it easier on himself and his characters. He seizes the tale of Gary and Alana as an opportunity to indulge in his favorite habits: curating a soundtrack of off-the-beaten-path oldies, exploring the halcyon LA of his boyhood dreams, setting up elaborate dolly shots in the way ordinary folks solve crossword puzzles. There’s been a palpable pleasure to every movie PTA’s ever made, his flashy, immodest style ensuring that much. But in the past, it’s felt like the man makes his movies because he’ll die if he doesn’t get all of this urgent, burning stuff out of him; here, one gets the impression he’s simply enjoying himself.

The more of a single director’s movies a person watches, the more inclined they are to divine some insights about the artist’s personal life from the stories they choose to tell and the way in which they tell them. Licorice Pizza suggests a PTA not in decline, but recline, allowing himself to relax in tone while maintaining his aesthetic rigor and slavish attention to detail. Unburdened by his distance to youth, wistful about its joys while clear-eyed about its foolishness, he’s made as graceful an entree to middle age as anyone can hope for. This is his “those crazy kids” movie, made in the knowledge that the phrase comes from a place of affectionate contentment. Behind each scene, there’s a smile and a shake of the head — an acceptance that the good times are behind us, and that that’s a fine place for them to be.

This article was featured in the InsideHook LA newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Southland.