This is the sixth volume of a weeklong series on the theme of fatherhood in the work of six contemporary filmmakers. You can read the rest here.

If you really want to know a man, ask him to describe his father. I can’t remember where I first heard this maxim — maybe Oprah, possibly Bill Belichick — but I’ve tested it a few times and have found that it’s quite true. What a man says or, just as tellingly, doesn’t say about his father will tell you a lot about his own identity. When applicable, the inverse also works. If you want to learn about a man, ask about his son.

Although fathers and sons don’t occupy the foreground of Nomadland, director Chloé Zhao’s lyrical Oscar snatcher, they deliver some of the film’s most poignant scenes. When Frances McDormand’s Fern asks her would-be suitor Dave (David Strathairn) why he’s reluctant to move in with his son’s family, Dave stumbles into introspection — with shades of Harry Chapin.

“I was … I was … he didn’t like it very much that I wasn’t around when he was young. I tried to be around when he was older, but he was into his thing and I was into mine. I guess I just forgot how to be a dad. Anyway, I wasn’t very good at it.”

Fern’s pragmatic response strikes an emotional chord. “Don’t think about it too much, Dave. Just go. Be a grandfather.”

And so he does. Zhao treats us to a subsequent scene where Dave and his son play a piano duet after Thanksgiving dinner, expressing their love through a medium that’s more comfortable than language.

Words, substantive and honest words, don’t always flow easily between fathers and sons. We probably need a Freud primer and an extended session with a male support group to understand why, but Chloe Zhao’s films all have something to say on the subject. This is particularly true of her first two features, Songs My Brothers Taught Me (2015) and The Rider (2017). With fraught, conflict-heavy scripts, they tell much more emotionally penetrating stories than Nomadland.

All three of Zhao’s films are set in the heartland. It may feel peculiar that a Chinese-born filmmaker has emerged as the leading chronicler of the American west, but sometimes an outsider’s perspective is the most honest. In a conversation with the director Alfonso Cuarón for Interview Magazine, Zhao explained the allure of the west.

“Growing up in Beijing, I always loved going to Mongolia. From the big city to the plains, that was my childhood. Spending a lot of time in New York in my mid-20s, I was feeling a bit lost. I always joke that historically, when you feel lost, you go west.”

And sometimes she’s not joking. After graduating from NYU’s film school, she was seeking inspiration for her first feature and felt listless in Manhattan. Moved by photojournalist Aaron Huey’s powerful pictures from South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, she felt compelled to visit. She immersed herself in the Lakota Sioux community, befriending many residents and absorbing the truths — material and emotional — of their experiences. These truths became the seedlings of her first two films. Both Songs My Brothers Taught Me and The Rider are set on the Pine Ridge Reservation. And, similar to Nomadland, both films rely on untrained actors playing fictional versions of themselves. Although Zhao is not the first director to employ this casting strategy, she is undeniably one of the most gifted at harnessing authentic and mesmerizing performances.

Songs is a slow-burning family drama that revolves around two siblings, Johnny and Jashaun. They live with their mother on the reservation. She’s loving but struggles to take care of herself, let alone provide for her children, so it’s up to Johnny to look after his younger sister. An early montage shows him fixing Jashaun’s bike, teaching her how to box and smuggling alcohol in order to buy groceries. Their father, a traveling rodeo cowboy named Carl Winters, lives on the reservation but is absent from their lives. Shortly after the film opens, they learn that he has died in a house fire.

Carl’s funeral presents a complex portrait of fatherhood. In attendance are many of his 25 children along with many of their nine mothers. As he’s eulogized, the camera floats from one fractured family to the next. Different emotions are etched onto different bereaved faces — love and affection, jealousy and resentment, confusion and indifference — and Zhao uses the visceral expressions to let us see the spectrum of a dead man’s life. Carl was good, he was bad, he was human. His children mingle at a bonfire after the funeral — some of them meeting for the first time — and Zhao’s trenchant dialogue sharpens our awareness of Carl’s disparate approach to paternity. They go around and share why they decided to take or forego their father’s last name. Johnny and Jashaun use Carl’s name, but they do so without conviction. His ghost haunts the rest of the movie.

We never meet Carl or even see a picture, but his presence is ubiquitous. It’s in his jean jacket that Jashaun doggedly sports, well-worn and baggy. It’s in the truck that Johnny buys and discovers, after purchasing it, that it used to belong to his dad before he gambled it away. For both siblings, their inner and outer journeys are shaped by the trauma of losing a parent they hardly knew. 11-year-old Jashaun sets out to learn more about her father, a search that starts in the smoldering ashes of his house. Johnny grapples with a more pressing conflict.

As high school graduation nears, he has a chance to move to Los Angeles with his girlfriend and leave the reservation behind. When Johnny visits his older brother in prison, his brother urges him to go and not look back. But liberating himself from the desolation of his home means abandoning his sister. Just as this reality sinks in for Johnny and the viewer, Zhao shrewdly cuts to a scene of 11-year-old Jashaun smoking weed with an older girl and talking about boys. It’s harmless, yet we can’t help but wonder what her future holds if Johnny goes.

His crisis of conscience boils down to a war that all men wage in some form or another on the road to self-actualization. A son must reconcile his own identity with that of his father. If Johnny stays, he’ll never escape the world that molded (and broke) his father. If he deserts Jashaun, fleeing in his father’s truck no less, he’ll commit the same familial crime for which he resents his father. It’s a catch-22 that Zhao probes in achingly beautiful detail.

Although the director’s accolades tend to focus on her distinct aestheticism — poetic landscape celebrations that have rightly drawn comparisons to Terrence Malick — her instincts as a storyteller have fueled her success. Zhao’s gift lies in her ability to tell deeply personal tales rooted in universal truths. She’s only made three films, but there are already pulsing throughlines connecting them. She’s found that the thermodynamics of father-son relationships are fertile ground for evocative storytelling.

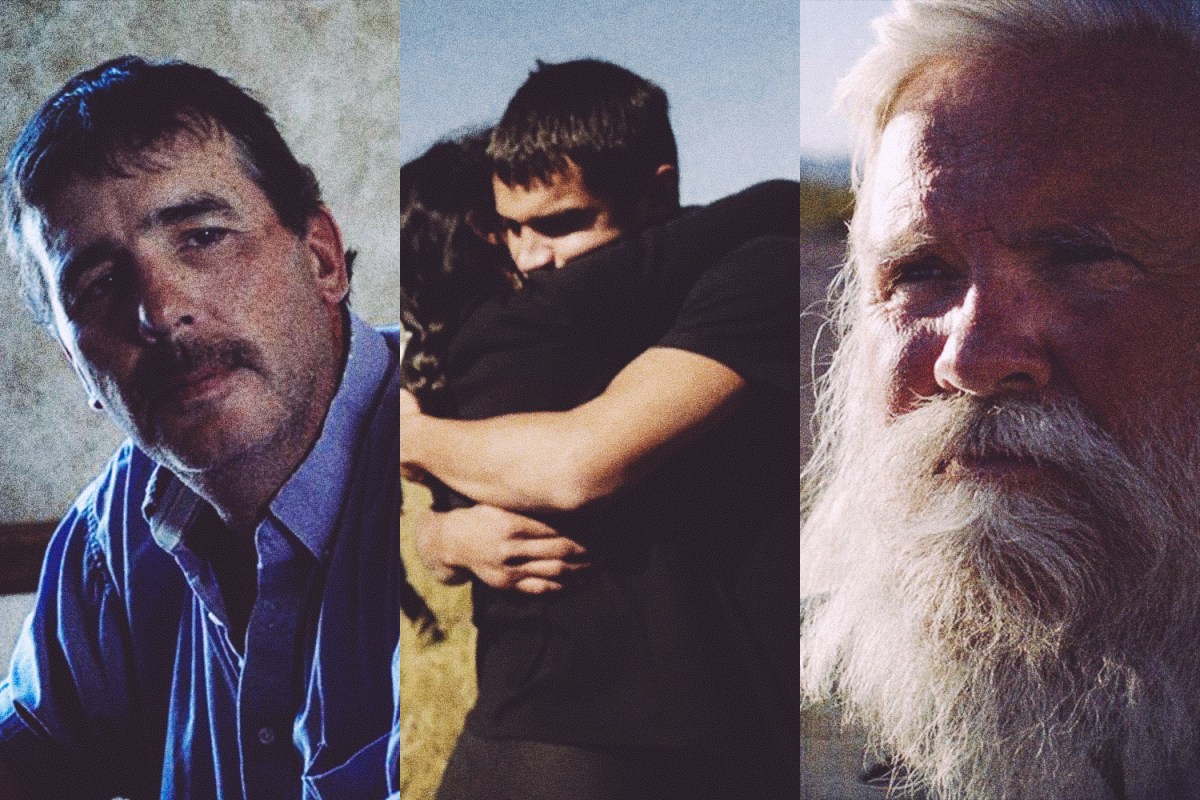

The Rider explores this terrain with superior technical and narrative prowess. It’s a masterpiece. At the heart of the story is Brady Jandreau, a rodeo cowboy who suffers a traumatic brain injury and is told that he’ll kill himself if he continues to ride. The premise isn’t novel (think The Wrestler), but the authentic pathos is unrivaled. Brady is played by Brady Blackburn, an actual cowboy Zhao befriended while making her first film. Blackburn suffered a similar injury in real life, and Zhao’s script draws heavily from his experience. His real father and sister join him on screen, and though the plot’s family dynamics are fictional, verisimilitude is easily achieved.

Tim Jandreau, Brady’s father in the movie (Wayne Blackburn in the flesh), is a widower whose demons diminish his ability to look after his children, but not his capacity to love them. Drinking and gambling are his particular vices. The consequences are a constant source of conflict between father and son, and their terse conversations almost always devolve into arguments. Not because they resent each other, but because they are overwhelmed with love. In their shared language of cowboy machismo, it’s much easier to express anger than affection.

The argument they return to throughout the film is whether or not Brady should rejoin the rodeo. It’s obvious that nothing scares Tim more than the prospect of losing his son, but he can’t bring himself to say that plainly. “Go kill yourself then,” he shouts during one heated exchange after Brady declares his intention to ride. “I’m not gonna end up like you,” Brady replies. And then they storm off in separate directions, as fathers and sons do.

The common ground between the two, however, is vast and touching. They both care deeply for Lilly, Brady’s cognitively disabled sister, and Zhao gets ample mileage out of the domestic triangle. There are plenty of lighthearted moments, like Brady and Tim working together to convince the reluctant Lilly that she should start wearing a bra. There are heart-wrenching moments too. Since their mother’s death, Brady has become a co-parent to his sister. It’s an emotionally taxing role, but one he assumes without hesitation or complaint. His maturity and sacrifices hold the family together as Tim self-destructively copes with his own grief, and Zhao masterfully portrays filial piety as a cardinal virtue.

Despite the father’s shortcomings, the son knows he owes him everything he holds dear. The film’s most indelible sequence is a montage of Brady breaking a wild colt. Blackburn, the actor, is a virtuosic horse trainer, and Zhao simply points the camera and lets him do his thing. It’s spellbinding. When the horse’s owner asks Brady where he acquired his gifts, he credits his dad.

Zhao’s first three films are all squarely situated in the world of independent cinema. That’s about to change. Her next project is Eternals, a Marvel blockbuster due out in November, and Universal Pictures recently announced that they hired her to write and direct a genre-bending Dracula movie touted as a “futuristic, sci-fi western.” Some fans are understandably wary that Zhao is selling out, but she’s been adamant that she’s tackling these projects on her own terms and telling the stories she’s always been interested in telling.

That’s a good sign for those of us who are excited to see how she continues to develop the dynamics of father-son relationships in her body of work. She should have plenty of material. When it comes to daddy issues, superheroes and vampires tend to have a few.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.