“Believe in yourself! Have confidence in your abilities!”-Opening lines of Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking, 1952

In 1957, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale was busted for lying on the hit game show What’s My Line?

Peale was a celebrity mystery guest on the program. Trying to guess his identity, a contestant asked: “Are you an important member of any particular religion?” Peale replied, “Not so much.” The host called out his false modesty. Peale was the pastor at Manhattan’s Marble Collegiate Church, but his influence went far beyond New York. He had a radio broadcast, a newspaper column, and a number of books, including The Power of Positive Thinking. (Positive Thinking is believed to have sold at least 15 million copies to date.)

And this was before Peale, who became known as “God’s Salesman,” played a major role in a presidential election… and arguably an even bigger part in a second race that occurred 56 years after it. Somehow this self-effacing man wound up linked with two modern masters of bare-knuckle politics: Richard Nixon and Donald Trump.

This is how Peale helped bring positive thinking to the presidency and why he might struggle to recognize what it’s become.

A Hopeful Man for Horrible Times

Peale was born on May 31, 1898 in Bowersville, Ohio. The son of a Methodist minister, he was ordained as well. Peale would later recall his father observing one of his sermons and saying, “In your desire to impress people with your own profundity, you seem to have forgotten that the way to the human heart is through simplicity.”

It wasn’t only “simplicity” that shaped Peale’s work. (Though critics would indeed accuse him of being simplistic.) Other characteristics included:

–Directness. As Peale put it: “I talk to my audience as if it were one person instead of 2,500.”

–Entertainment. His sermons would be neither grim nor solemn: “People retain ideas longer if they hear them in a good mood.”

–Practicality. Peale liked to address topics he could handle in a “simple, practical, 1-2-3 manner.”

In 1932, Peale shifted to another Protestant denomination, joining the Reformed Church so he could serve the Marble Collegiate Church. He would be the pastor there for 52 years. His faith soon took on a scientific component. With Smiley Blanton, he established what became the Blanton-Peale Institute & Counseling Center in the Marble Collegiate Church basement in 1937.

Blanton was a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and patient of Sigmund Freud. Decades later, he paid tribute to Peale: “He was one of the first men – if not the first – to combine the new science of human behavior known as depth psychology with the discipline of religion. As a result, he has been able to help more people than either religion or depth psychology could help, acting alone.”

Peale believed in mental health: “We must approach the maladies of our emotional life as a physician probes to find something wrong physically.” He also believed we had a great deal of control over our well being: “Without a humble but reasonable confidence in your own powers you cannot be successful or happy.”

Indeed, with the proper attitude we could achieve remarkable things against even seemingly long odds: “Any fact facing us is not as important as our attitude toward it, for that determines our success or failure. The way you think about a fact may defeat you before you ever do anything about it. You are overcome by the fact because you think you are.”

From 1917 to 1945, America endured two World Wars and a Great Depression. Now Peale offered enjoyable, easy-to-digest sermons that asserted you had the power to make yourself happy and maybe even rich. Remembering his father’s suggestion, Peale found the perfect concise expression of this concept: “God is in you.”

Unsurprisingly, Peale proved popular to ambitious Americans. Indeed, one of them remained deeply fond of him even after Peale may have cost him the presidency.

An Inept Endorsement

In 1960, Peale joined a group of evangelical ministers who declared that a vote for John F. Kennedy was to risk letting the Catholic “bring American foreign policy into line with Vatican objectives.” Kennedy had long denied the pope would shape his presidency: “I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic party’s candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me.”

Nixon felt this message a step too far, doomed to backfire: “I knew we were in for trouble.” Did it cost him the 1960 election? It’s impossible to say for certain, but it was a remarkably close outcome. The final popular vote was 34.2 million for Kennedy and 34.1 million for Nixon. While Kennedy opened the gap in the electoral college (303 to 219), an impressive number of states were competitive. Six had a margin of victory under one percent.

Peale regretted the statement and publicly apologized to his Manhattan congregation in the most self-effacing manner possible: “I never been too bright, anyhow.”

Things got worse for Nixon—he ran for governor of California in 1962 and lost that too. Of course, Nixon did reach the White House, taking the presidency in 1968. He still held Peale in high esteem. In 1970, Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman wrote in his diary that he asked Nixon what kind of funeral he’d like and got this response: “He wants simplicity, only one DC service, at Rotunda, no horse. Need a layman for the eulogy, no ideas. [Billy] Graham and Peale for prayers.”

Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974. He died in 1994. (Graham officiated at Nixon’s funeral, just as he had done for Nixon’s wife and mother.) Peale himself passed at age 95 on December 24, 1998. President Bill Clinton paid tribute: “Dr. Peale was an optimist who believed that, whatever the antagonisms and complexities of modern life brought us, anyone could prevail by approaching life with a simple sense of faith.”

Nearly two decades later, Peale found himself unexpectedly back in the news and in power.

Peale’s Greatest Pupil?

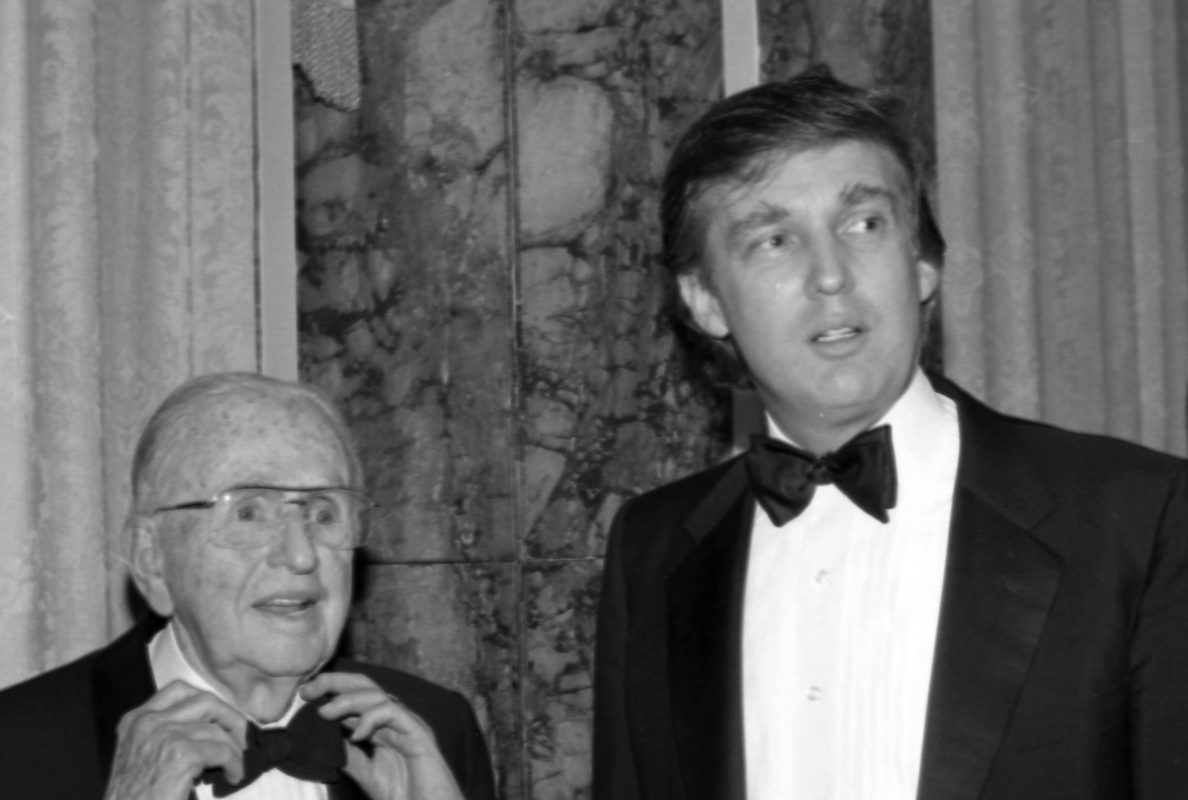

Fred and Mary Anne Trump attended Marble Collegiate Church with their children. Peale made a particularly profound impression on one child. To this day, Donald Trump praises Peale as “a wonderful person” who could “give the best sermons of anyone; he was an amazing public speaker. Trump reports the respect was mutual: “He thought I was his greatest student of all time.” Peale even officiated Trump’s first marriage, to Ivana Zelníčková.

At the time of Peale’s death, the prospect of Trump becoming president seemed less unlikely than plain impossible. He was undergoing one of the messiest chapters of his professional and personal life. His businesses sought Chapter 11 protection in both 1991 and 1992. Trump’s marriage to Ivana had fallen apart as his affair with Marla Maples became public knowledge. Maples gave birth to their daughter Tiffany two months before they married on December 21, 1993. Peale died three days later.

By 2009, Trump was on better footing. He gave an interview to Psychology Today: “My father was friends with Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, and I had read his famous book, The Power of Positive Thinking. I’m a cautious optimist but also a firm believer in the power of being positive. I think that helped. I refused to be sucked into negative thinking on any level, even when the indications weren’t great. That was a good lesson because I emerged on a very victorious level. It’s a good way to go.”

Six years later, Trump ran for president and soon found himself in the White House, putting Peale’s theories to the test every step of the way.

Positive Thinking’s Power…

When Trump entered the race back in 2015, the odds of him winning were 25 to 1. Not quite Buster Douglas and his 42-1 shot at taking Tyson, but incredibly slim. This made sense. For starters, Trump had only been a Republican since 2012—voting records show he changed parties at least five times. He seemed to stumble from self-inflicted wound to self-inflicted wound, as he insulted a Republican war hero for being captured in Vietnam. (Trump avoided service through five deferments, including once for bone spurs in his heels.) He then feuded with the family of a soldier killed in Iraq. Even what for most candidates would be routine steps turned into epic battles, as he has yet to release his tax returns despite repeated promises to do so over the last three years.

And all the while Trump remained unrepentant, digging in and lashing out when conventional wisdom dictated he should have offered a quick apology followed by an attempt to change the topic. Or maybe gone into hiding for a bit or even just given up the ghost completely and shifted his focus to 2020.

A Peale observation: “Action is a great restorer and builder of confidence. Inaction is not only the result, but the cause, of fear. Perhaps the action you take will be successful, perhaps different action or adjustments will have to follow. But any action is better than no action at all.”

It was definitely true in Trump’s case. If nothing else, his frenetic run seemed to lull his opponents into overconfidence and a corresponding inertia. Take early Republican favorite Jeb Bush. His massive war chest of $159 million ultimately translated into just three delegates. With a campaign that never kicked into gear, Trump famously tagged him as “low-energy.”

Or Hillary Clinton in the general election. Curtis Wilkie, whose books include The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, covered Bill Clinton’s successful runs in the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections. Wilkie got to know Hillary as well, telling RCL he found her “smart as hell” and “much more charming than came across [in public].” He was baffled by her 2016 effort, however, observing simply that she ran a “fairly s—– campaign.” She and her team felt assured of victory, with Obama reportedly musing that defeating Trump was “too easy.” Pundits all too often agreed. Statistical analyst Nate Silver—who went 99 out of 100 on states in 2008 and 2012—confidently predicted a Clinton victory, utterly failing to recognize the surprising high probability of his later eating several pounds of crow.

Trump just kept on moving forward until he reached the White House, where he applied positive thinking more aggressively than ever.

…And Problems

Here’s the hard truth about obstacles: Some are insurmountable, no matter how hard you work and how upbeat your thoughts. Because of them, we don’t always get what we want. Sometimes we even fail at tasks as basic as controlling our own emotions. As most who’ve gone through a traumatic experience can attest, just making sense of your feelings afterwards can take time, much less coming to terms with them.

Peale’s critics felt he failed to reckon with these realities. The psychiatrist Robert C. Murphy stated that Peale was so busy asserting that problems will “evaporate if thoughts are turned into more cheerful channels” that Peale lost sight of many of life’s realities: “For him real human suffering does not exist.”

Once elected, Trump experienced similar issues. He wanted the world to appreciate how epic his triumph was. Thus he would declare, for instance, that he had the “biggest Electoral College win since Ronald Reagan.”

This was incorrect: Obama had won 332 just four years earlier.

Trump then insisted he referred only to Republicans.

This was also incorrect: George H.W. Bush had won 426 in 1988.

Similarly, then White House press secretary Sean Spicer insisted, “That was the largest audience to witness an inauguration, period.” Trump repeatedly made a point of noting “it looked like a million-and-a-half people.” These claims were almost immediately proven incorrect—for one, photos clearly showed a drop in attendance from Obama’s 2009 inauguration. It’s now estimated that somewhere between 250,000 and 600,000 people attended in 2017, compared to 1.8 million in 2009.

Trump’s failure to match Obama’s mark hardly came as a shock. After all, Trump had lost the popular count by roughly three million votes, collecting just under 63 million votes. Beyond the excitement generated by becoming the first black president in 2008, Obama had won handily—he collected over 69 million votes and triumphed by nearly 10 million. There was no reason to expect Trump to approach Obama’s attendance, making his denial when he failed to do so all the stranger.

Of course, this is ultimately a trivial matter. Beyond maybe the candidates themselves, who cares about margins of victory or attendance? But Trump has repeatedly seemed to let his positive thinking prevent him from facing downbeat facts—over 4,000 false or misleading claims have already been documented during his time in office. Has it impacted his credibility? Well, 2018 did witness a uniquely awkward moment at the United Nations:

When Trump does confront unpleasant news, he has a tendency to insist others are responsible. Thus he said that Republican congresswoman Mia Love lost her 2018 reelection because she “gave me no love.” Love actually hadn’t been defeated at that point, but a week later her loss was confirmed. During her concession speech, Love said she had been “somewhat surprised” by his comment: “What did he have to gain by saying such a thing about a fellow Republican?”

In some ways, Trump has been a remarkable endorsement of Peale: Positive thinking brought a former student to the presidency! Then again, Trump has to this point proven a historically unpopular president. Gallup polling found he’d yet to top a 45 percent approval rating for any week.

It’s worth asking: Is Trump truly a reflection of Peale’s values?

Peale on Peale

One person who feels Trump has strayed from the fold is his son, John Peale, an ordained minister and self-described Democrat. He has stated the connection with Trump makes him “cringe”: “I don’t respect Mr. Trump very much. I don’t take him very seriously. I regret the publicity of the connection. This is a problem for the Peale family.” In particular, he feels Trump puts too much emphasis on “material success” and “doesn’t recognize the significant character of Dad’s ministry, which is a sincere desire to help people.”

How would Norman feel about Trump today? Obviously, he can’t speak for himself. But there are some undeniable divergences from his teachings. Peale is a link between Richard Nixon and Donald Trump. Of course, those presidents have another acquaintance in common: Roy Cohn. Trump had no illusions about that lacerating lawyer. The Art of the Deal notes: “I don’t kid myself about Roy. He was no Boy Scout. He once told me that he’d spent more than two-thirds of his adult life under indictment on one charge or another. That amazed me.”

It’s the Cohn influence and not the Peale that’s visible when Trump tweets: “When somebody challenges you unfairly, fight back – be brutal, be tough – don’t take it. It is always important to WIN!”

Whereas Norman Vincent Peale mused, “You will soon break the bow if you keep it always stretched.”

Also: “Watch your manner of speech if you wish to develop a peaceful state of mind. Start each day by affirming peaceful, contented, and happy attitudes and your days will tend to be pleasant and successful.”

As noted, Peale collaborated with a psychiatrist. He certainly understood a touch of academic rigor could be brought to religion, even describing faith as “a scientific procedure for successful living.”

Science often deals with numbers. So did Peale on occasion. That’s why he urged each person to “make a true estimate of your own ability, then raise it 10 per cent.” Because even Peale recognized you can only be so positive.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.