A baby-faced Jay-Z hovers in the hallway, relaxed in red sweats, ropes of gold chains on his neck. He was 18 when this picture was taken by music photographer Timothy White, a longtime veteran of magazines like Rolling Stone and Esquire. But Jay was not at all famous at the time, merely showing up to an event in support of his friend, rapper Jaz-O. White rediscovered the image in his archives by accident within the last decade — of course at the time he shot it he had no idea that its subject would become one of hip-hop’s most enduring icons. The Morrison Hotel Gallery’s new exhibition “Hip Hop Nation: Retracing the East Coast x West Coast (R)Evolution” features countless icons like Jay-Z from the genre’s past and present. (The exhibition will run until September 15, while a simultaneous show at the Los Angeles location features different photos.)

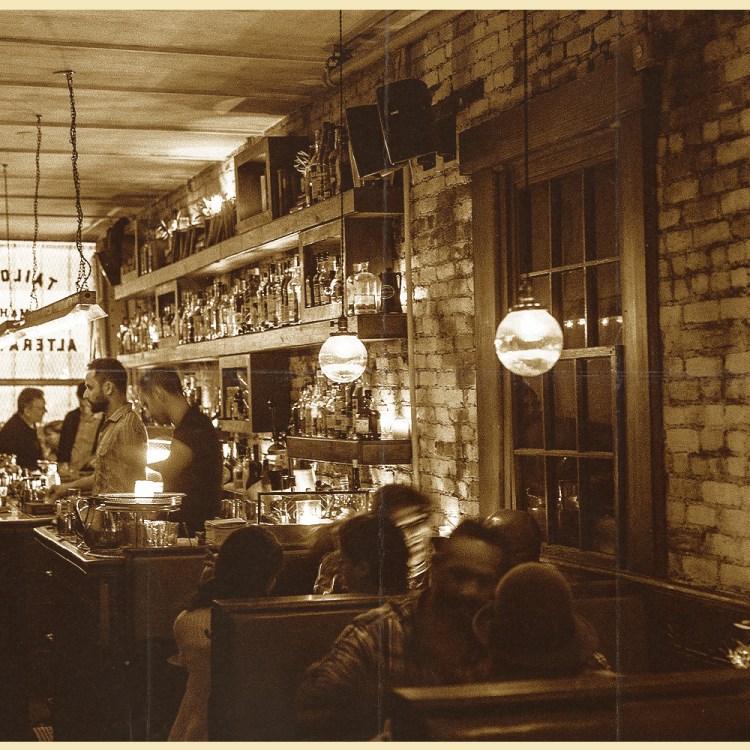

The recent opening night party in Soho House’s Meatpacking District featured a selection of images, as well as beats by DJs MixMaster Mike and Yamez. Entering the party, down the stairs to the venue’s Vinyl Room, Jay’s was the first face greeting partygoers. The dark room was bathed in purple, blue and magenta lights save for the images lining the wall, lit with warm tones to reveal their subjects, people whose names need only one word to announce their presence: Snoop behind a wheel photographed by Mike Miller, Biggie with a joint by, a curl of smoke suspended in his lips by Geoffroy de Boismenu, a splash of Kendrick by Travis Shinn. But let us also not forget an early photo of Public Enemy, the days when Flav’s dangling clock was so much smaller (Danny Clinch). Of Run DMC and the Beastie Boys laughing together on a rooftop in 1987 (Ebet Roberts). NWA in 1990 (Lynn Goldsmith). Beyoncé in 2006 (Clinch). Ye and Jay suited and crouched together in discussion, posed to resemble Robert and John F. Kennedy in 1960 (Clay Patrick McBride). Guests circulated, taking pictures of the artwork, while sipping cocktails out of heavy crystalline glasses. Overhead Rob Base & DJ EZ Rock’s “It Takes Two” was spinning as people in clusters of light that later evolved into groups danced to songs like Mary J’s “Real Love” and Big Boi’s “Kryptonite” or mouthed the lyrics to Biggie’s “Juicy.” There was something about listening to the music while seeing photos of icons who sang them that went well beyond the scope of a traditional gallery setting.

The condensed version of the show on display at Soho House will eventually travel to the venue’s Chicago, Nashville and Austin locations. The full version of the Morrison Hotel Gallery’s New York exhibition was curated by gallery art advisor Breanne Palmieri and assembled in time to celebrate what’s generally considered to be hip hop’s birthday, August 11, 1973. (This was the date legendary DJ Kool Herc threw a back-to-school jam in the Bronx at 1520 Sedgewick Avenue thought to have been the first to cement all of hip hop’s influences in one place.) Accordingly, the show covers iconic figures from hip-hop’s history, from Grandmaster Flash all the way through to Lil’ Kim, Aaliyah, Wiz Khalifa and A$AP Rocky, among many others.

The images challenge viewers with middle fingers and puffs of smoke, diamonds and tattoos, bandannas and cufflinks, smiles and grills. New for the show is a never-before-seen lenticular, or holographic, print of Barron Claiborne’s portrait of Biggie, a $6 plastic gold crown perched on his head (that sold at auction in 2020 for $600,000) in front of a red background, which toggles between the image of the rapper and a skull. Produced in an edition of 12 — Claiborne usually makes his Biggie images in editions of 24, the age the rapper was at the time of his death — it retails for $6300.

Looking at the work, it’s plain to see how the visuals around hip-hop have changed over time. In 1989, NWA wanted to be photographed where the sewage let out in LA; the Beastie Boys were shot in front of a graffiti-covered wall in New York in 1987. But today, Palmieri says, there’s much more studio work — in an age when artists can provide their own behind-the-scenes content on social media, images made in the studio lean towards spectacle in a way they hadn’t before. The show aims to capture this evolution, both the visual and the historical. Indeed, the evolution is palpable, seen through the images of artists who paved the way for the form’s transformation. It is also an instant reminder for viewers about where they were when they heard some of this music for the first time. It only makes sense they’d get to remember how it looked, too. With this show, they can.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.