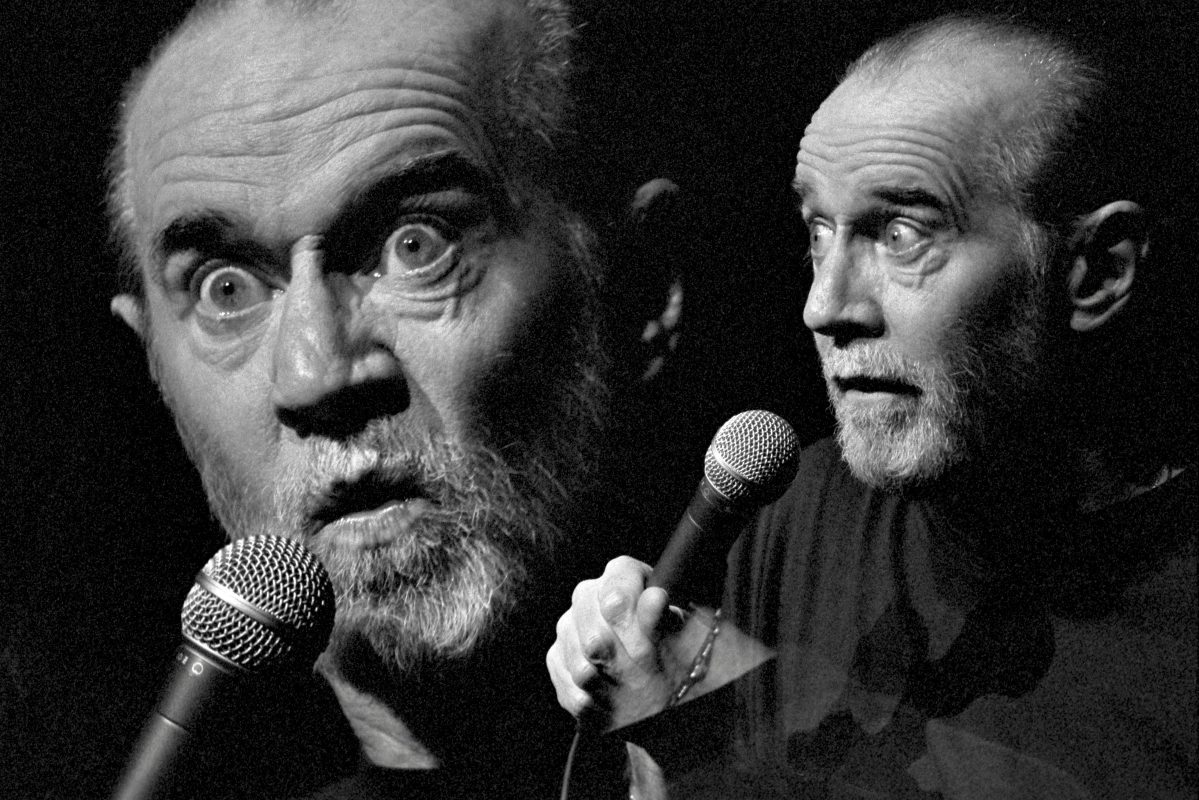

On April 25, 1992, George Carlin walked onstage to the applause of 5,600 people at Madison Square Garden’s Paramount Theater and delivered an hour-long stand-up performance in which he channeled Nostradamus even more than he did Lenny Bruce, his comedy hero.

“In this country, the whole social structure — just beginning to collapse,” he said in the 46th minute. “You watch.”

Well, we have watched, for 30 years, and since that night when HBO presented George Carlin: Jammin’ In New York live for a cable audience, the majority of Amerians have, unwittingly or otherwise, adopted his outlook. A January poll by NPR and Ipsos found that 70 percent of Americans believe the country is in crisis and at risk of failing. This at least partly explains why in the 14 years since Carlin’s death people have kept his spirit alive online, in meme form and through reposts of his bits on social media, many of which originate in the Jammin’ special, Carlin’s personal favorite of his own productions.

Its level of prescientness is astounding upon a present-day rewatch.

Carlin went on to explain during his routine that he’s an entropy fan and looking forward to the country’s downturn because it’s sure to make for exciting TV. Among the carnage he’d hoped to find while flipping channels were oil refinery explosions, tornadoes hitting churches on Sundays and “some guy running through a K-mart with an automatic weapon firing at the clerks.”

All that ought to sound pretty familiar. Among the dozens of oil spills since then, there was the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico that killed 11 people and devastated the surrounding ecosystem. There’s also been an increase in extreme weather events, due in large part to global warming, that have caused billions of dollars in damages, while displacing and killing many. Mass shootings have dominated headlines on a regular basis, so much that I don’t think I need to provide a supportive hyperlink here.

We’ve also seen people “killing policemen in the street” and 2,000-point daily stock market drops, both of which Carlin crossed his fingers for that April evening.

“It just means more fun for me!” he said, literally dancing, at the conclusion of his TV news wishlist. “That’s just the kind of guy I am!”

Of course, he was kidding. He’d satirically assumed the persona of a red, white and blue-blooded American, most of whom, he said afterward, refuse to admit they’d tune into the chaos, too. For that they’d earned the label “lyin’ assholes.”

While he’d already proven himself an astute observer of social behavior trends for years, this level of darkness and vitriol was fairly new to Carlin’s act. According to his daughter, Kelly, who I interviewed in 2017 when the National Comedy Center debuted a cache of her father’s archives, Jammin’ marked a second pivot in George’s career. A few decades earlier he’d repositioned himself from “straight comic” to counterculture voice. But while protesting the establishment through jokes, he still maintained an even-keeled, ironically upbeat tone of speech. The bleakness he tapped into — the anger he expressed in Jammin’ — was allowed after the emergence of Sam Kinison, the roaring former preacher turned controversial comic who peaked in the 1980s and died in a car accident two weeks prior to Carlin’s Paramount Theater performance.

“Sam gave him permission and really helped him see, ‘Oh, now we have to scream at these people because that’s how asleep they are,’” Kelly Carlin told me.

For Kinison’s inspiration, George Carlin dedicated Jammin’ to him, with a white-font message over a black screen at the top of the broadcast that read “this show is for SAM.” Having self-sprinkled in more than a single helping of Kinison outrage into his already legendary observational comedy, Kelly’s father “found his true artistic voice” in 1992, she told me — which he retained the rest of his career.

Ted Alexandro, a comic who began his time as a performer that same year and always felt “a kinship” with Carlin, marvels at the comedy veteran’s willingness to learn from someone so much his junior at the time. “It also shows humility,” Alexandro, 53, says, impressed that Carlin would go so far as to splay his appreciation for another comic — and competitor — at the beginning of a special.

But any comedian will tell you that the marker of success in a stand-up performance, no matter the volume of the comic’s voice or even how perceptive and wise they come across, is laughs. Carlin was as good at manufacturing funny as anyone who’s ever grabbed a microphone.

“Carlin is the best comedian, pound for pound,” says Mark Normand, 38, a popular stand-up performer, highly regarded for his exceptionally tight joke writing. “He has all the disciplines. He has the puns, stories, word play, joke-jokes; he has clean, he has dirty, he has observational.”

Normand notes that Carlin didn’t delve into personal history onstage; however, that’s a more recently developed comedy trend and can’t be counted as any sort of demerit against him. If audiences today were going to have a problem with Carlin, it might be with some of his pre-woke-times rhetoric, which turns up in Jammin’ when he targets women living with bulimia and anorexia in the 33rd minute.

“Beverly Hills has a brand new restaurant specifically for bulimia victims; it’s called ‘the Scarf and Barf,’” he said. “How about a restaurant for anorexics?” he continued. “What would you call it? ‘The Empty Plate.’”

Culturally, we’re much more sensitive to people living with eating disorders and mental health issues than we were 30 years ago, and undoubtedly, as Normand tells me, Carlin would be “totally crucified today” for statements like these. But a closer examination of the bit reveals Carlin’s obliviousness to the fact that women of any social standing might deal with such illnesses. When he put his exclamation point on the segment, he said he can’t sympathize with a woman who’s anorexic and added: “Some rich cunt who doesn’t want to eat? Fuck her.” On bulimia, he said it was a made-up, “all-American disease” that reveals our dubious cultural values. “[We] gotta be the only country where some people are digging in the dumpster for a peach pit; other people eat a nice meal and puke it up intentionally,” he said.

“What I thought immediately [about the bit] was, ‘He’s trying to make this a class thing,’ which is what he’s adept at,” says Laura Peek, a Los Angeles-based comic who watched Jammin’ in the run up to our conversation — though she’d seen it many times before. “It made me realize that culturally things just really change and it makes me feel grateful for the shifts that happen.”

In spite of our progress, few if any people seem to ever want to retroactively cancel George Carlin in the way they have with John Wayne, for example. Instead, they prop Carlin up as a philosophical prophet, with timeless takes fit for memeification.

“He was usually in the right,” Normand says. “And he was so poised. Every word was chosen; he was so meticulous…So when you go back to [his work], there’s not an extra word, there’s not too much fluff.”

Normand says comedy nowadays contains tons of “filler.” Comics appear on podcasts, he says, where they can get “loosey goosey” with their trade. But with Carlin, Normand continues, even if a young person listens to his precision and profundity they can’t help but think, “Damn, that was a hell of a rant,” something that’s lacking these days.

“He was unflinching in his analysis of America and of its place in the world, which still puts him in very rare space,” Alexandro says. “There’s a real appetite for that, always, but especially now, and there’s not a whole lot of that going on.”

Jammin’ might be best known for its opening nine minutes, with lessons that Alexandro believes are still “applicable” today. Carlin assaults the federal government and the mainstream media for its handling of the country’s first armed conflict with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq a year earlier. Though it had been a “popular war,” Carlin saw through the White House-communicated motives. President George H.W. Bush said Hussein’s “aggression will not stand” — a quote famously mimicked by The Dude in The Big Lebowski — and painted the U.S.’s mission as one of liberation on behalf of Kuwait. It would’ve been easy for Carlin to point out that, truly, the government imposed itself upon Hussein out of fears he’d come to control too much of the world’s oil reserves. (When one war fought for this reason wasn’t enough, Bush’s son sparked a second 12 years later.) But just about anyone with a respectably sized intellect could’ve deduced that themselves. So instead, Carlin presented the Persian Gulf War as the manifestation of toxic masculinity — without using that precise term, of course, as it wouldn’t permeate the zeitgeist until the 2010s.

“To me war is a lot of prick-waving,” Carlin said. “Men are insecure about the size of their dicks and so they have to kill one another over the idea. That’s what all that asshole jock bullshit is all about; that’s what all that adolescent macho male posturing and strutting in bars is all about. It’s called ‘dick fear.’”

He then posited that because President Bush had been called a “wimp” for so long, and because Hussein essentially dared him to respond to his invasion of neighboring Kuwait, Bush felt inclined to resort to war, truly, to preserve his self-esteem. In between yucks, Carlin also delivered a pointed message about individual freedom, expression and thought that turns up frequently on social media: “I got this real moron thing I do, it’s called ‘thinking,’” he said. “And I’m not a very good American because I like to form my own opinions.”

Quips like that one, Alexandro believes, might have kept Carlin from being treated so well by corporate entities like HBO, Netflix or Amazon, all of which are home to thousands of stand-up specials, if he was twirling them today. But Carlin would have probably made do with material like the following 22 minutes of Jammin’, where he discusses trivial experiences that many people share (trying to get someone to rub dirt off a particular spot on their face, only to watch them touch every other epidermal area instead) and, later, the insulting mundanity of airplane travel announcements (“Seatbelt…high-tech shit!”)

“Who else could turn on a dime and go from commentary about the U.S. war machine to the minutiae of looking at your watch and not knowing what time it is?” Alexandro asks hypothetically. “Those are two polar-opposite styles.”

It’s Carlin’s diversity and craftsmanship that has helped his legacy endure, as well as his soothsayer status and willingness to comment on big, critical issues that amazingly, dishearteningly remain topical.

On the first Persian Gulf War, he said in Jammin’, “Now we only bomb brown people,” a stance that mixes nicely in with the current juxtaposition between the U.S.’s support of Ukraine and its indifference toward the humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen, which our government has helped sponsor with the sale of arms to Saudi Arabia.

“We do come to the defense of people who need it as long as they’re white,” Peek says. “How are we still having these exact same conversations generations afterwards?”

In Jammin’, Carlin also discusses climate change, middle-class division and how its persistence serves the rich and the ruling class, and even how human beings are susceptible to viruses — though he was alluding to HIV at the time.

Born just a year before Jammin’ In New York first aired, Peek, who as a teen had friends turn her on to Carlin, says watching the special back then made her “such a different type of person, a more aware type of person.”

It also helped shape her into the comic she is today. Peek says Carlin showed her that, onstage, she can and should tackle serious topics and goings-on that bother her. “Things that you’re very disturbed by, that you don’t find funny,” she elaborates, “that you think are really abhorrent and strange and make you uncomfortable.”

It’s those talking points that the comic, ultimately, has to make funny, which is no small task and requires hours upon hours of hard work.

“And he was the G.O.A.T.,” Peek says. “He was the best at that who ever lived.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.