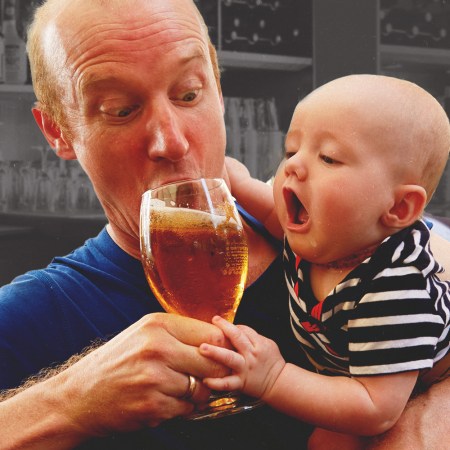

It’s a millennial social-media cliché: when you get to a certain age, Facebook and Instagram go from mostly selfies and bragging about your vacation to about 50 percent baby photos. While there are certainly those who grumble about the infantilization of their feeds, the majority of people — whether it’s family, friends or that family friend whose caps lock button appears to be jammed — seem to appreciate parents who share their adorable day-to-day moments.

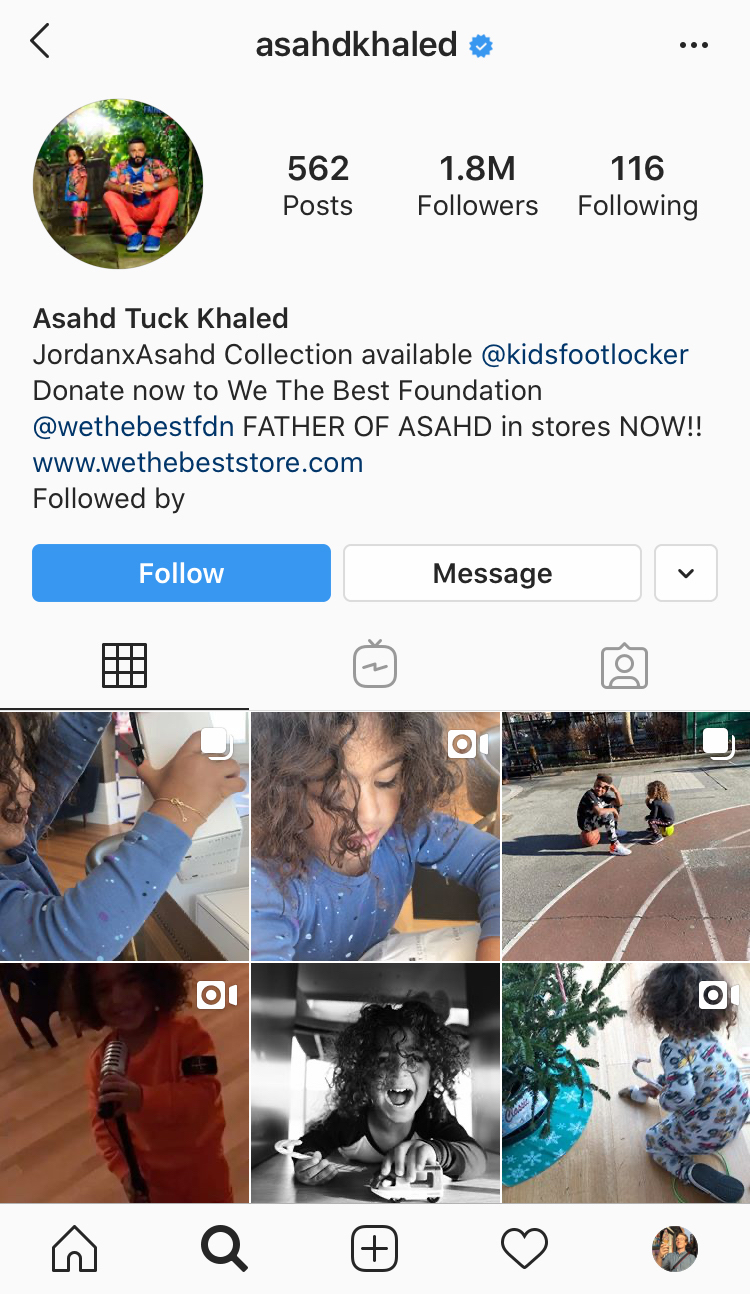

In fact, young children seem to be doing almost alarmingly well in the world of social media. The highest paid YouTube star of 2018 was a seven-year-old who reviews toys (he made $22 million in one year, according to Forbes). DJ Khaled’s 3-year-old son Asahd, whose birth was documented on Snapchat, has 1.8 million Instagram followers. There’s even eight-month old Alessi Luyendyk, child of Bachelor alums Arie and Lauren, who has 317K followers for an Instagram account that was set up six whole months before birth.

While there seems to be a chasm between a celebrity kid getting sponsorship deals and your cousin who occasionally posts updates on her toddler’s height, they’re both on the same spectrum of parenting in the millennial age. Generation Y, the group born between 1981 and 1996, is the first to grow up with social media. In other words, they’re the first to opt in to — or out of, if they so choose — what has become an unprecedented, fraught, intimate experience in global sharing.

Consequently, the children of those millennials will be the first generation to have their entire lives (sometimes from the moment of conception) documented on social media, without the agency to choose for themselves whether or not they want to enter our digital landscape. The term digital native comes to mind, but that seems too benign.

“Let’s say I decide that I want to put really embarrassing pictures of myself online. That is completely my own choice. I have no one to blame but me with the level of risk that I have chosen to assume,” Leah Plunkett, author of Sharenthood: Why We Should Think Before We Talk About Our Kids Online, tells InsideHook. “But let’s say that I am doing the same thing for my son who is still in elementary school. He has no recourse against me. I’m his mom, I can do that. Unless I’m putting up an image that is, heaven forbid, illegal or criminal … the law is not going to step in.”

Does “recourse” sound a bit like an overreaction? How much harm can sharing a picture of your newborn on Instagram really cause? Instead of thinking about it as a single photo, think about all the data being potentially being shared about a child through a parent’s account: full name, date of birth, hospital tagged in an Instagram, photos from every age, schools and institutions they attend, etc.

Taking all that into context, this may not surprise you: according to forecasts from Barclays, by the year 2030, two-thirds of identity fraud cases concerning young people will be the result of “sharenting,” or parents sharing the personal information of their children.

“If we are subjecting our kids and teens … to surveillance, both in real time, if we’re using surveillance tracking technology, or down the road because we’re leaving a really indelible trail of what they do, then we’re depriving them of that protected space.”

Leah Plunkett, Author of Sharenthood

That’s not all. Plunkett, an associate dean and associate professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, writes in Sharenthood about three areas of concern when it comes to sharing photos, videos and other details about your kids online: concerns that “relate to consequences that are criminal, illegal, or otherwise dangerous,” such as identify theft or child pornography; concerns that are “invasive, opaque and suspect,” like data brokers harvesting and selling information; and concerns about the child’s sense of self, because by posting about them (and defining their experience) parents could disrupt that developmental process.

“If we are subjecting our kids and teens — who really deserve, I argue, the most latitude for messing up because they’re still learning — if we subject them to surveillance, both in real time, if we’re using surveillance tracking technology, or down the road because we’re leaving a really indelible trail of what they do, then we’re depriving them of that protected space,” said Plunkett.

Millennial parents, as well as most social media users, are at least somewhat aware of the pitfalls of social media; they’ve been plastered across the frontpages of news sites (and physical newspapers) for years, from the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica data harvesting scandal in 2018 to this fall’s revelation that millions of Flickr images were being unknowingly used to train facial-recognition algorithms.

Unfortunately, awareness doesn’t equal understanding, and the general public probably will never fully grasp the vulnerability of their personal information and all the ways in which it has been appropriated. Sure, it’s part willful ignorance, but it’s also incomprehensible Terms and Conditions agreements, as well as the general exchange we as a society have agreed to make of privacy for convenience. But children don’t have the ability to make that choice, and while adults always have the option to delete their tweets or YouTube videos, minors don’t have control over the content created around them, which makes the prevalence of “sharenting” even more egregious.

One could make the argument that the social media platforms themselves should be held to a higher standard. But again, there are those Terms and Conditions users agree to without reading, and as it stands, it is in their interest to expand wherever possible, and that includes taking on child users.

Of course, most platforms have an age limit. So how does one set up an account for a minor, like DJ Khaled’s son’s Instagram? The company, which is owned by Facebook, stipulates that users must be at least 13 years old (or older in some areas), but when I reached out to a Facebook company spokesperson, they said it has been their policy for years to allow younger people to have accounts as long as they’re run by parents or “managers.”

That seems like treacherous water to tread, as the role of manager isn’t clearly defined, so how is Instagram policing that? According to the spokesperson, those accounts are required to clearly state in the bio that it is run by a parent or manager. But the account of Asahd Khaled, one of the most popular child Instagrammers, has no such text (at the time of publication), despite the account being verified by Instagram with a blue checkmark.

Of course, this particular account may have had the necessary text when Instagram verified the account, but that’s not the point. The point is that — despite their supposed security measures, privacy tools and image-building PR campaigns — social media companies have never been able to guarantee that anything you share with them is safe from misuse, and by now parents need to know that lack of protection now extends to their kids.

It isn’t all bad news, though. Plunkett said she is vehemently not a technophobe, but instead goes about it in a “values-based way,” and she does see a bright spot in this increasingly vague future.

“As a law professor, I feel compelled to add … that laws change,” she said. “We have a generation increasingly coming of age that is going to be the first generation to really reckon with adults with this kind of digital dossier built for them. So they could change the statutes or regulations, right? If they elect the right lawmakers.”

As we’ve seen in the last decade, that’s a big “if” to rely on. Instead, the millennial generation could get out in front of this issue and protect their children, instead of leaving it up to them to reckon with the consequences — that is, if they can pull themselves away from their screens for a second.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.