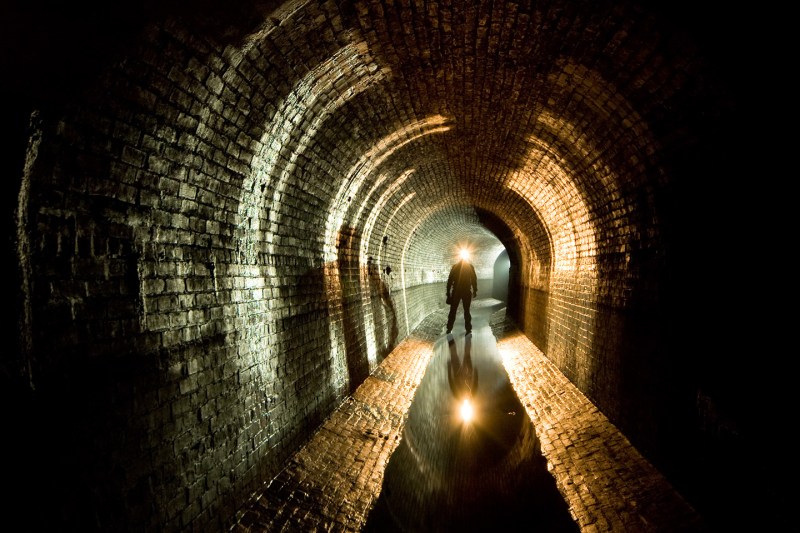

Most people move through tunnels and across bridges safely encased in metal and strapped to their seats. Urban explorer and historian Steve Duncan does the opposite; from crawling through caverns in Ukraine to trudging through sludge beneath Las Vegas, he brings the world a vantage point that otherwise would remain a mystery.

RealClearLife asked Duncan, who has appeared on The Discovery Channel and Vice, three burning questions we wanted to know from someone who has seen the world through a unique set of eyes. These answers have been edited for length and clarity.

RCL: What sticks out in your mind as the most dangerous situation you’ve found yourself in because of urban exploring?

Duncan: I think the most dangerous situations I’ve been in have all involved underground rivers or sewers, and especially when I first started exploring these kind of places and I still didn’t know much.

In cities, where there is so much pavement, any rainfall quickly turns into runoff which then immediately begins to flood drainage and sewer tunnels. When a sewer or underground river begins to flood like this, it’s deadly — a tidal wave of water filling up the tunnel in minutes, and it can happen from even a fairly small amount of rain.

When I first started, I didn’t really understand this, and I also wasn’t thinking much about tides. I had the silly idea that once we build a big city, the “natural” world no longer has much impact on it. I learned better when I found myself trapped in a giant storm drain underneath Queens, NYC.

A friend and I had gotten in near where the outlet of the tunnel emptied into Jamaica Bay (which is part of the Atlantic Ocean, and so it is affected by tides). We hiked inland —upstream — for a few hours, and I was excited because I realized that this huge drain tunnel approximately followed the route of an old stream that had existed on the surface long before the city developed over it. But then the water suddenly started rising, and we realized that it had started raining on the surface above us, and all that water was pouring off the streets and sidewalks and rooftops of Queens and we would be drowned if we didn’t get out as quickly as possible.

We fought our way back toward where we had gotten in as quickly as we could, trying not to lose our footing in the rushing water, only to encounter my second important lesson of the day: Apparently we had gotten into the tunnel during low tide, and in the meantime the tide had started coming in.

It was clear the end of the tunnel was now completely underwater, even if we could have gotten to it, which we couldn’t, because the incoming tide was now flowing into the outlet of the tunnel even faster than the rainwater was trying flow out, and as it rose above waist level it became impossible to fight through it.

On top of everything else, now things bumped into my legs in the murky water, and I wondered what strange and terrifying things might be washed into the city’s underground from the ocean (and I hoped none of them were hungry).

We were terrified, and we decided to do something that normally is pretty dangerous in New York: To escape from the first manhole we could find. This is dangerous because in NYC almost all manhole covers for drains and sewers are in the street. The biggest tunnels usually are directly beneath bigger — and thus busier — streets, meaning that there is always the danger if you open a random manhole cover from below that a car will come along at just the wrong time and break your neck, or — just as bad for us — get a wheel stuck in the suddenly-opened manhole, thus blocking our escape route with a couple tons of automobile.

It was a truly horrible feeling when I climbed up the ladder and braced my shoulder against the cover, and found I could not budge it at all. My partner joined me and we perched on the ladder in the darkness and we both worked at it but there was not the slightest movement.

We had no choice, so we kept on going to the next manhole shaft, in water which was now up to our chests. We also couldn’t budge this one. I was beginning to think about how embarrassing my obituary would be (headline: “Semi-employed Brooklyn man drowns in sewer; he should have known better!”) when we found a third manhole shaft at a junction with a slightly smaller tunnel. Probably it was because not as many cars had pounded over this one that I was able to crack it open.

I pushed it aside and scrambled up, my partner following on my heels, and I’ve always wondered what the driver of the oncoming car thought as she slowed down and gaped at us, both of us streaming water, headlamps still shining, terrified and dirty, but so incredibly glad to be alive.

It rained for the next two days and there was flooding in some parts of Queens, meaning that the tunnels beneath the streets had entirely filled up and started overflowing. Ever since I’ve kept in mind that no matter how artificial and man-made a city might seem, it still exists as part of the same natural processes that have always been part of the landscape. And of course, I check rain predictions and tides very, very carefully …

RCL: Having visited all of these underground places around the world, what have you learned about humanity?

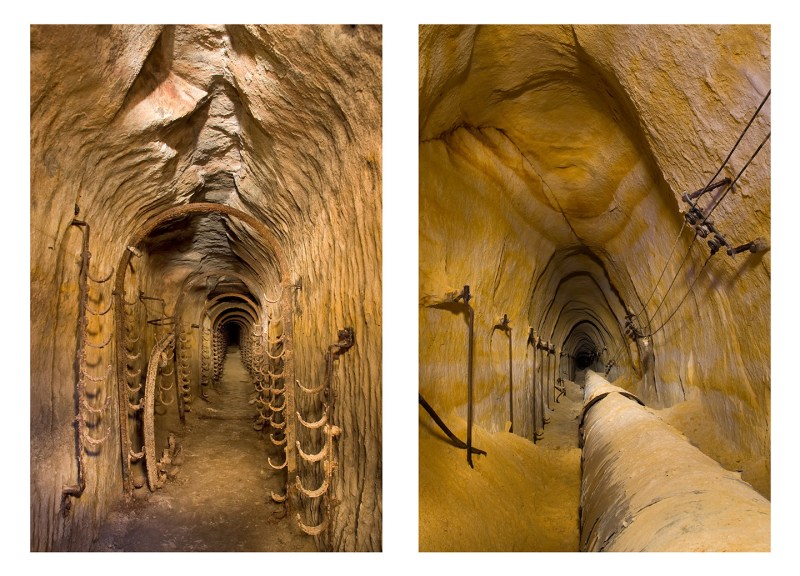

Duncan: Going underground in cities is fascinating because — just as with archeology or geology — it often seems that the deeper you go, the more you are going into the past.

Each era of a city has its own magnificent infrastructure projects. We grumble about the subway’s imperfections and completely forget just how remarkable it is that hundreds and hundreds of miles of tracks carry us underneath the streets and even underneath the rivers. We turn on the water and we take it for granted that we can use, in NYC, an average of about 140 gallons per day per-person of drinking-quality water, coming to us from a range of sources between 40 miles and 100 miles away from the city.

The very first subway station — the flagship City Hall station, the initial station of the first subway line– sits abandoned and dusty today, and when I see it I always think that it is a perfect metaphor for how quickly we forget the triumphs of past generations, a forgetfulness that happens when we so take them for granted that we stop seeing anything remarkable about them.

If you peel back enough years of urban development, eventually you would get to the pre-urban landscape; and the interesting thing for me is that this landscape still exists, hidden under streets and buildings, and the same natural processes that have always occurred keep right on happening even though we have done our best to hide them away. Rain still falls, water still flows, even natural springs still bubble up, although now they generally flow directly into sewer tunnels rather than ever seeing the surface. We tend to forget this, though, or at least I did until I started exploring these places; I had just assumed, quite wrongly, that when a city of a few million people grows up, it just completely replaces all the “natural” processes that had been going on.

RCL: What advice do you have for people who are interested in urban exploring?

Duncan: When people ask me about how they can start doing urban exploration, usually I start thinking about all the gear I take with me on my most extreme adventures: multi-gas meters, hip-wader or chest-wader boots, manhole hooks, fancy headlamps and expensive flashlights, occasionally an inflatable kayak, even a climbing harness with a few dozen meters of rope and anchors to attach it to if I am worried about being swept away while taking pictures of some particularly fast-flowing underground river. But really I started with just a cheap $5 flashlight and too much curiosity, and for years I figured that was all I needed.

A lot of people who call themselves urban explorers focus on abandoned places, and definitely these can be fascinating. Walking into a dusty old factory or asylum or even an abandoned home can seem like stepping into a time capsule. But I don’t think people should limit themselves to abandoned places.

I think the best thing is just to find something that piques your interest, and then try to follow it, wherever it leads! Train tracks are particularly good for this sort of thing; find some old freight train tracks that go through your city or nearby, and then try to figure out where they lead, and walk along them.

Or look on an old map of your city and find one or two old streams that don’t seem to exist on contemporary maps, and try to figure out where they go. Sometimes there are helpful clues, like streets named “Creek Lane” or “Mill Pond Alley;” or you might find that in the present-day city there appears to still be the same old creek running through parkland, but when it gets to the edge of the park it simply disappears. Where does the water go? Once you find yourself asking this question, or even just looking down as you walk along and wondering what’s beneath this or that manhole cover, then you have become an urban explorer!

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.