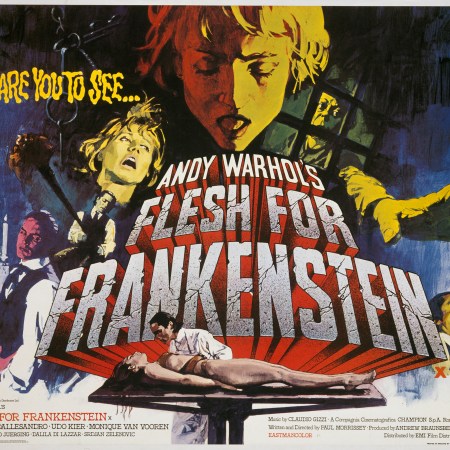

Warning: this post contains major spoilers for Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein.

Somewhere along the way, over the 200-plus years since Mary Shelley first published her classic Gothic novel, we kind of lost the plot with Frankenstein — or, more accurately, Frankenstein’s monster, also known as The Creature. You know who I’m talking about: green guy, bolts in his neck, flattop, walks with his arms outstretched and mostly communicates in grunts. The most enduring images of The Creature in pop culture actually have next to nothing to do with the way he’s described in Shelley’s Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus; in the book, he’s eight feet tall with yellow, translucent skin, and most importantly, he’s incredibly intelligent — so much so that he’s able to eloquently narrate his own story for a chunk of the novel.

So compared to the schlocky creature features we’ve grown accustomed to, Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein (in theaters now in limited release, on Netflix beginning Nov. 7) is much closer to Shelley’s original vision. It’s not exactly surprising, of course, given del Toro’s previous work; he’s got a long history of crafting sympathetic monsters in films like Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water. But despite his obvious reverence for Shelley’s tale, the director did take some major creative liberties for his version — most noticeably by changing the ending.

An Updated Canon: 72 Books Every Man Should Read

We’re not tossing out the old masculine lists, but we’re giving them a much-needed refreshIf you paid attention in your high-school English class, you know that the book ends on a grim note in the Arctic, with Viktor Frankenstein dead — a victim of his own hubris — and the Creature wandering off into the frozen tundra where, he says, he plans to throw himself onto a funeral pyre. It’s a poignant message about the dangers of playing god and the importance of treating people with kindness (violence begets more violence, etc.). But del Toro’s adaptation ends on a slightly more hopeful note: As Viktor starts to succumb to his wounds, he apologizes to the Creature, calls him “son” and reminds him that life is a gift, one he shouldn’t throw away. The Creature, who came there to kill him, is moved, and the two make amends before Viktor finally dies. The ship captain, having witnessed all this, orders his men to lower their weapons and let the Creature leave peacefully. To thank them for this, he pushes their boat out of the ice, allowing them to start their journey home safely. He then heads off on his own, gazes at the horizon and smiles a tiny bit as he sheds a tear. The implication is that he’s decided to follow his creator’s advice and continue living.

Upon first viewing, I hated this. It seemed like a schmaltzy, Hollywood ending to an otherwise excellent movie — one that undermined Shelley’s original intent. I didn’t mind del Toro’s other changes: Much has been made about the decision to cast Jacob Elordi as the Creature and whether the Australian actor is simply too good-looking to believably play a character whose appearance is famously monstrous, but I say it’s 2025 — let Frankenstein be hot. If anything, it helps us buy into his unspoken romance with Elizabeth (Mia Goth), another del Toro addition that improved the story, despite making the guy seated directly behind me mutter “oh, COME ON” at one point. Deleting Elizabeth’s marriage to Viktor and making her one of the few people who treats the Creature with warmth and respect helps hammer home just how awful Viktor is. We don’t need a sympathetic love story for him; he is, ultimately, an arrogant narcissist who dismembered a bunch of bodies without a single thought about who they once belonged to or whether they’d consent to their remains being sewn together. He treats the Creature like an animal and keeps him chained up. Of course Elizabeth would be more interested in the gentle Creature than a guy who ultimately amounts to the 1800s version of a tech bro obsessed with biohacking.

The ending, however, took me longer to come around to. It’s such a huge deviation from the original text — optimism instead of despair, redemption and forgiveness instead of total destruction. But now, having had a few days to sit with it, I think it’s the version of Frankenstein we need in this moment. Critics have (rightly) dubbed Paul Thomas Anderson’s recent One Battle After Another “the defining film of its generation” for the way it speaks to the times, but maybe Frankenstein is del Toro’s way of addressing current events as only he can. Now more than ever, we need to see examples of what happens when we treat people who may look different than us like human beings instead of something to be feared. As cheesy as it sounds, del Toro’s ending is an important reminder of the power of love. If you give it out, you get it back.

As del Toro’s Creature points out at one point, it’s tough to blame a wolf for being a wolf. It didn’t ask to be born a predator, just like he didn’t ask to be sewn together and brought to life during a thunderstorm by a mad scientist. When a wolf — or any other animal, really — kills, it’s not doing so out of malice; it’s just trying to survive. Cruelty, on the other hand, is uniquely human. Shelley’s novel is an important reminder of that, a twist on the old “hurt people hurt people” concept. But the book is also a product of the time it was released. For a little context, in 1818 when Frankenstein was originally published, the United States was still 45 years away from the Emancipation Proclamation. Is it any wonder that readers who may have still owned slaves would have trouble seeing and appreciating someone else’s humanity? With that in mind, Shelley’s book ends on a somewhat cynical note: Human beings are flawed, and we’ll always opt for violence, pain and fear over respect and kindness when given the choice. There’s no world, in Shelley’s version at least, in which the Creature could go on and live happily; he’s doomed from the start.

And look, I’m not saying we need a Frankenstein where the Creature rejoins society and goes to work in a bank or something. But these are dark times, and maybe we all could use a version of the story that recognizes the goodness in people and encourages us to bring it out more frequently. We always knew that the Creature wasn’t really a monster. But maybe, this new ending posits, we’re not, either.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=450%2C450)

![Noah Wyle [third from left] with the season 2 cast of "The Pitt"](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/the-pitt-season-2-schedule.jpg?resize=750%2C500)