This article is part of our brand-new Adventureland series, a collection of “how to” field notes from academic experts, modern explorers and endurance athletes throughout the world. From escaping bears to crossing deserts, they detail the joys of courting adventure — and their tips for surviving it.

Adam Stern was backpacking around Southeast Asia “cruising around, having fun, drinking, all those things,” when he stumbled upon a free diving school.

“There weren’t many free diving schools in the world back then. I thought, ‘Wow, cool’ and signed up for their standard beginner course,” explains Stern, a garrulous, energetic Australian, as he recounts the origin story for how he became one of the best free-divers in the world.

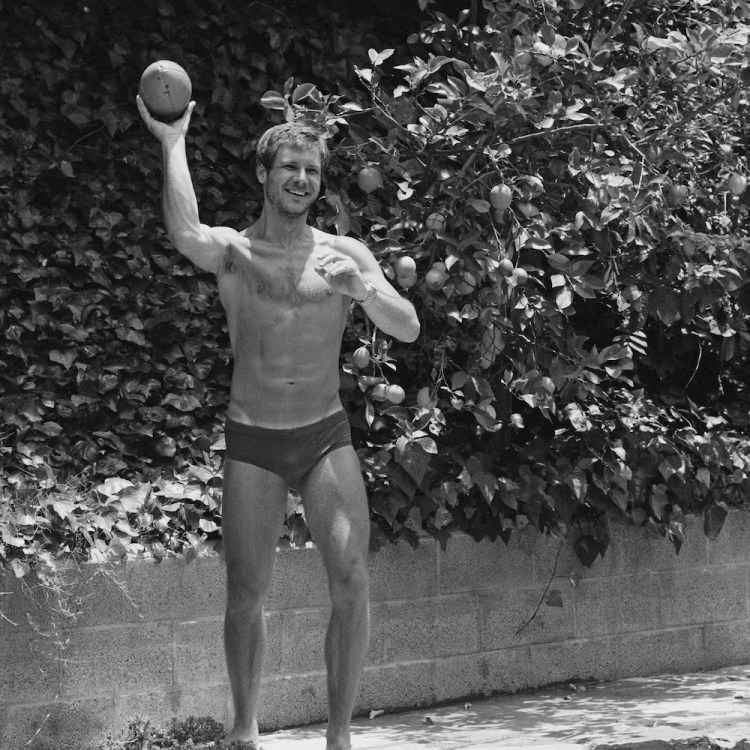

“I didn’t grow up diving, I grew up surfing,” Stern explains over a late night phone call from Australia. Now 35, Stern was just 21-years-old when his free-diving journey began.

“I was actually doing a scuba diving course when I saw the free diving school,” he says. “And honestly, I just thought to myself, ‘That looks so much better than what I’m doing.’ I was already bored with scuba diving.”

The problem with scuba diving, as Stern sees it: “Scuba diving is just you just dive down to look at a fixed object. And once you’ve seen the things, well, you’ve seen the things. I kind of felt like I was going back to the zoo again and again to see the same animals. There was no introspection, there was no connection to the world around you, you were this clunky observer with a tank on your back wrapped up in all this equipment.”

Free-diving, by contrast, opened up the aquatic world. “I immediately felt liberated,” Stern recalls. “I felt like I could completely use the verticality of the ocean. You can move in any direction, however you like. I was connected to the ocean in this amazing way. When you’re scuba diving, you’re making so much noise, you’re a bit of a clunky beast. It’s not natural, and all the aquatic life are afraid of you. But when you’re free to get real close like any other big fish swimming through, it’s a much more intimate, connected experience.”

The more he learned, the more in love he fell with the sport. The nature of his travels changed too. Instead of journeying to X, Y, Z to see the usual tourist spots, it became: “I’m gonna go here and dive, or I know that that person’s there and they’re a really good diver, so I’m gonna train with them.”

Stern absorbed all he could, progressing to a point where his mentors suggested he begin entering free-diving competitions. He threw himself into it with typical enthusiasm, eventually becoming one of the five best free-divers in the world.

Also known as “breath-hold diving” or “skin diving,” free-diving has its origins in traditional fishing techniques and involves diving down as deep as one can without the use of scuba gear, relying on breath-holds instead. Russian Alexey Molchanov set the world record in 2023 when he dove down to 121 meters (397 feet). After studying worldwide, Stern set the current Australian record of -99m and a personal best of -106m using fins.

In addition to being incredibly good at diving into the blue depths of the ocean on a single breath, Stern enjoyed the lifestyle. “I would duck away overseas and live somewhere cheap,” he says. “I spent two years training in Egypt, on the Red Sea. Or I’d train in Asia, or in the Caribbean, places where you could subsistence-live on very little. I’d go work my guts out at some shit job in Australia for three months and spend the rest of the year overseas training.”

After a while, Stern noticed that this kind of freedom was infectious. Strangers began approaching him, asking for lessons. Gradually, he build up a free-diving school in Australia — now one of the country’s biggest and best, with locations in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Brisbane and along the Gold Coast. It was only when he had his second kid that Stern realized, “There is probably not an acceptable amount of risk involved in this game anymore” and retired from competitions to focus on teaching full-time.

Despite his reluctance to put his own life on the line in pursuit of trophies, Stern says that free-diving isn’t inherently any more dangerous than other extreme sports. “Free-diving as a sport is as dangerous as the person who’s doing it,” he says. “When you do anything to an extreme level, there’s added risk. If you looked at the rate of heart attacks during ultra marathons, you’d be like, ‘Oh, wow, ultra marathons are a fucking dangerous activity, right?’ We teach free-diving with a bunch of parameters: ‘Here’s what we do, here’s what we don’t do.’ When we teach it, it’s the safest extreme activity in the world.”

Whether you’re interested in giving free-diving a go, or simply looking to improve your breath-holds, Stern’s advice can help.

The 10 Best Breathing Exercises for Sleep, Fitness and Calm

There are a lot of tricks out there. Keep these in your toolkit.How Can I Up My Breath-Holding Game?

“We have some really basic reflexes that will that make holding your breath uncomfortable, but as soon as you know what those are, you know how to deal with them, then all of a sudden, you’re like, ‘Wow, I can hold my breath for several minutes and I’m very comfortable,’” says Stern.

He’s mostly referring to the build-up of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream. Our urge to inhale comes not because our body knows it’s low on oxygen — there are emergency stores of oxygen-rich red blood cells in the spleen, for example — but from wanting to expel this CO2.

That being said: if you take a breath underwater, you’ll drown. Instead, you need to learn how to ignore the CO2 build-up in a safe way.

The first step is understanding the above, and how this makes you feel. “It’s not ‘Holy shit, I’m gonna die,’ it’s ‘Oh, that’s just a feeling that I get, and it’s OK,’” Stern says.

The second step is getting used to holding your breath. “[At one of my schools] I would guide you through a style of breathing to prepare you. Just laid stationary, I guarantee you, you would hold your breath for several minutes before you felt any discomfort or real desire to get rid of carbon dioxide,” Stern says.

He is, of course, reluctant to share the exact tricks of his trade, and it would be reductive to summarize decades of insight in one article, but Stern is clear to stress that when it comes to free-diving, at least, breath-holding isn’t the be all and end all.

“You don’t really think about your breath-holds very much on an actual dive, because there’s a lot going on,” he says. “The way we teach someone to dive is procedural, we start by teaching them all the basic physics and physiology involved. Then we do some dry breath-holds lying on the floor. Then we take them to the pool, and do some breath-holds with them laying facedown in the water. And then we go for a dive. By the time that a person is diving, they’ve done various breath-holds in various conditions. So it’s all controlled and they don’t have to stress about their breath.”

In terms of actual diving, the key is to advance gradually. Stern’s students follow a rope line down, first aiming for five meters of descent, then seven, then 10 and so on. “If for any reason you feel uncomfortable, you turn around to come back up,” he says. By doing so, you build up your ability to go deeper and hold your breath for longer, but it’s a gradual process, with a focus on fun rather than setting records. Crucially, it’s done as safely as possible.

“We’re not in the game of fighting the urge to breathe,” Stern says. “The next step after wanting to breathe is blacking out.” By that stage you don’t have the presence of mind to respond properly, so Stern says you should never try to power through, and should always know your limits, training gradually a few meters and minutes at a time. If you’re expecting instant results, well, don’t hold your breath.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.